Mali and a new War or Terror: Cameron goes where Blair went before – but at what cost?

The Prime Minister's decision to send troops to Mali is the product of an ill-defined nightmare of religious terrorism and "gesture" politics. He may come to regret it

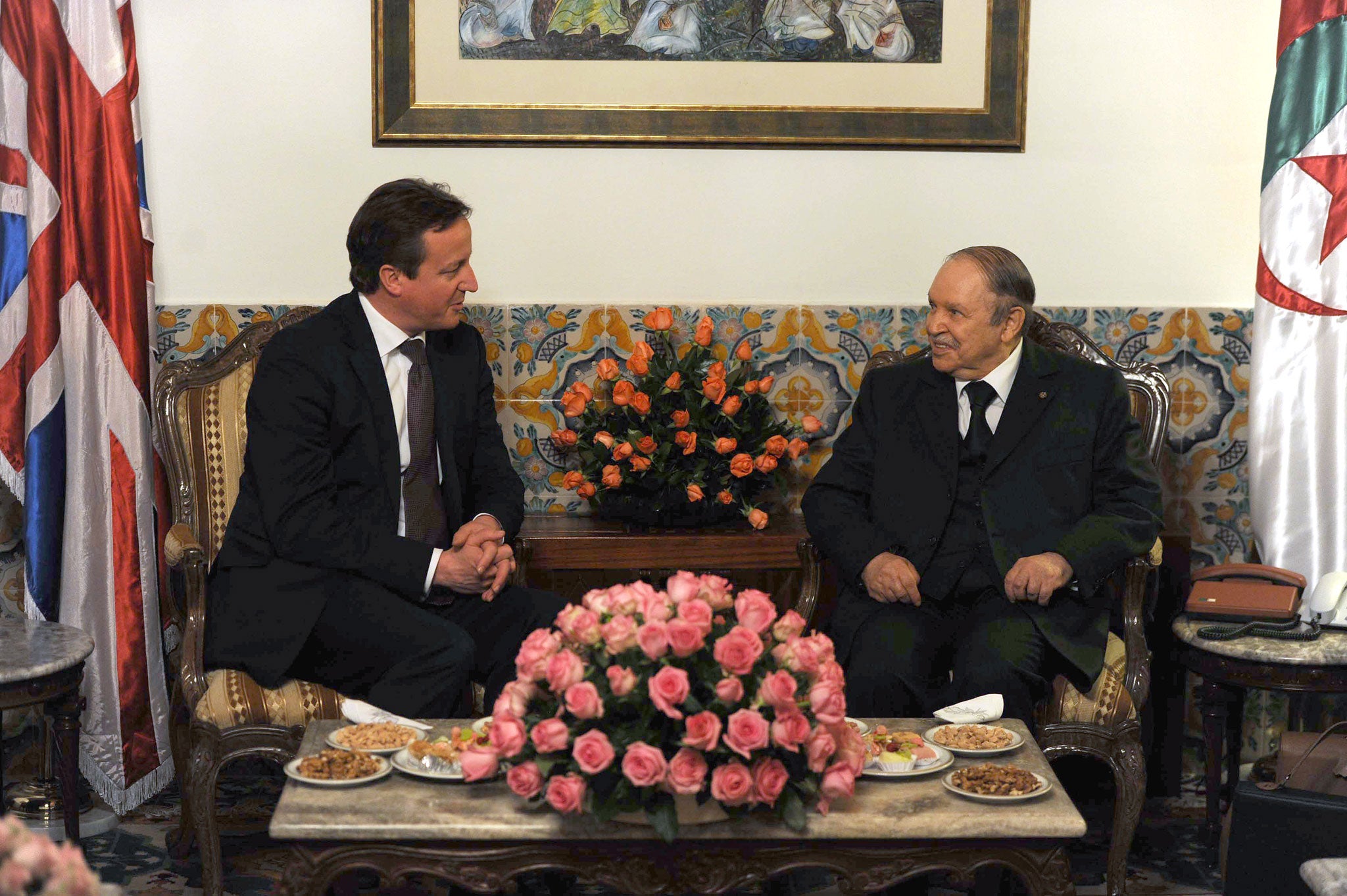

Everyone was too polite to mention it, including members of the sizable press group accompanying the Prime Minister on his “historic” visit to Algeria this week, but it was only a week ago that No 10 was briefing the media that the Algerians were acting precipitately, if not irresponsibly, in attacking the hostage-takers in the desert.

All that, along with the hostages killed, has been quickly forgotten as David Cameron now proclaims a new, tighter security and defence relationship with a country hitherto regarded as pretty close to a police state with scant regard for human rights when it came to suppressing Islamic opposition.

We had all this, of course, when Tony Blair decided to embrace Colonel Gaddafi and forget his human rights record when he appeared as an ally in the “War on Terror”. Now we have a newly refreshed War on Terror in North Africa and it’s Algeria which a successor Prime Minister clasps to his bosom.

The parallels are not exact. Algeria is not the same as Gaddafi’s Libya and the self-sufficient Algerians are a lot less eager to welcome and take advantage of British blandishments than the wily Colonel was. But the essential reasoning is the same – we are facing a global threat of terrorism and must fight it with every weapon, and every ally, at our disposal. The difference, of course, is that we can no longer look to the US for a lead. President Obama is rightly wary of such engagements. And the British public, too, is warier of foreign entanglements than it was when Blair gaily took us to war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

They are right to be. It is all very well for David Cameron to declare that the 330 British servicemen being sent to Mali will only be there for training proposes. But one has to ask, as some in France are now asking: what happens in a year or so if the rebel groups re-emerge from the desert to overwhelm the Malian and other African forces stationed in the recaptured towns of the north.

The rebels, after all, have not been defeated in battle. They have chosen to retreat rather than fight. If they come back, can the British, along with the French, refuse to join the battle?

It’s not that we are wrong to offer assistance to Mali and to try and build up regional cooperation in defending it and other states. There is a real danger for Europe and the wider world from the threat posed by insurgent groups invading states too weak to defend themselves. The question is how to define that threat and then develop the policies to meet it.

The essential danger is to the survival of states. That is an issue that should be tackled at the level of the UN and the region. Muddling it up with all sorts of ill-defined nightmares about religious terrorism only confuses the issue.

Yet that is what the Prime Minister is doing. His decision to send troops to Mali, his sudden trip to Algeria, and his pronouncements there that he will be increasing the military budget after 2015 are all political gestures of a Prime Minister trying to “own” developments rather than determine them.

Given the immediate success of French intervention, the rumblings of his backbenchers over defence cuts, and the advantages of masking British withdrawal from Afghanistan with something more positive, you can see the attractions of making North Africa a British cause.

The one clear lesson from all our foreign engagements, however, is that you have to have a clear purpose in view. Gesture politics always end badly.

The meaning of Israel’s Syria strike

The Israeli strike on Syria on Wednesday remains shrouded in mystery. But then that is always the case with Israel’s extra-territorial exploits. Half the message it gives is the uncertainty and, therefore, the unpredictability of its attacks.

In this case, there are two versions of its air assault. One, carried by the Syrian press, is that it was aimed at a chemical plant near Damascus. The other, from intelligence sources in Washington and Europe, is that the target was a convoy carrying advanced weapons from Syria to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Whether these were anti-aircraft missiles, as US sources suggest, or chemical weapons, as Israeli reports indicate, is open to question. The problem with intelligence briefings is that you can never trust them. It suits Israel to raise such a spectre as cover for its confrontation with Hezbollah.

Whatever the case, the strike – and the tentativeness of the Russian condemnation – suggests the Syrian conflict may be entering its end game. Hezbollah wants its weapons stored there back in its own dumps. The Israelis, encouraged by Washington, want to stop the spreading of arms from the civil war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies