Legal highs give a snapshot of drug decriminalisation. And it's not all that pretty

University students of the class of 2011 were privy to the rise of mephedrone

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am about to break a rule of thumb. Along with my dreams (spooky), my favourite supermarket (Waitrose) and my going bald (yuck!), I promised myself I wouldn’t resort to regaling strangers with tales of “my university days” and “the drugs we did” in this column. So I’m sorry.

But it seems relevant today. Last week it was announced that the UK has the largest market for legal highs in the EU; nearly 700,000 Britons aged 16-24 have experimented (in their bloodstream) with one form or another. It’s a common line, repeated with varying levels of menace, but the new synthetically produced legal highs – like the just-banned N-Bomb – bear roughly the same relationship to vintage predecessors –herbs like Salvia – as a bungee jump does to a mild bout of trampolining.

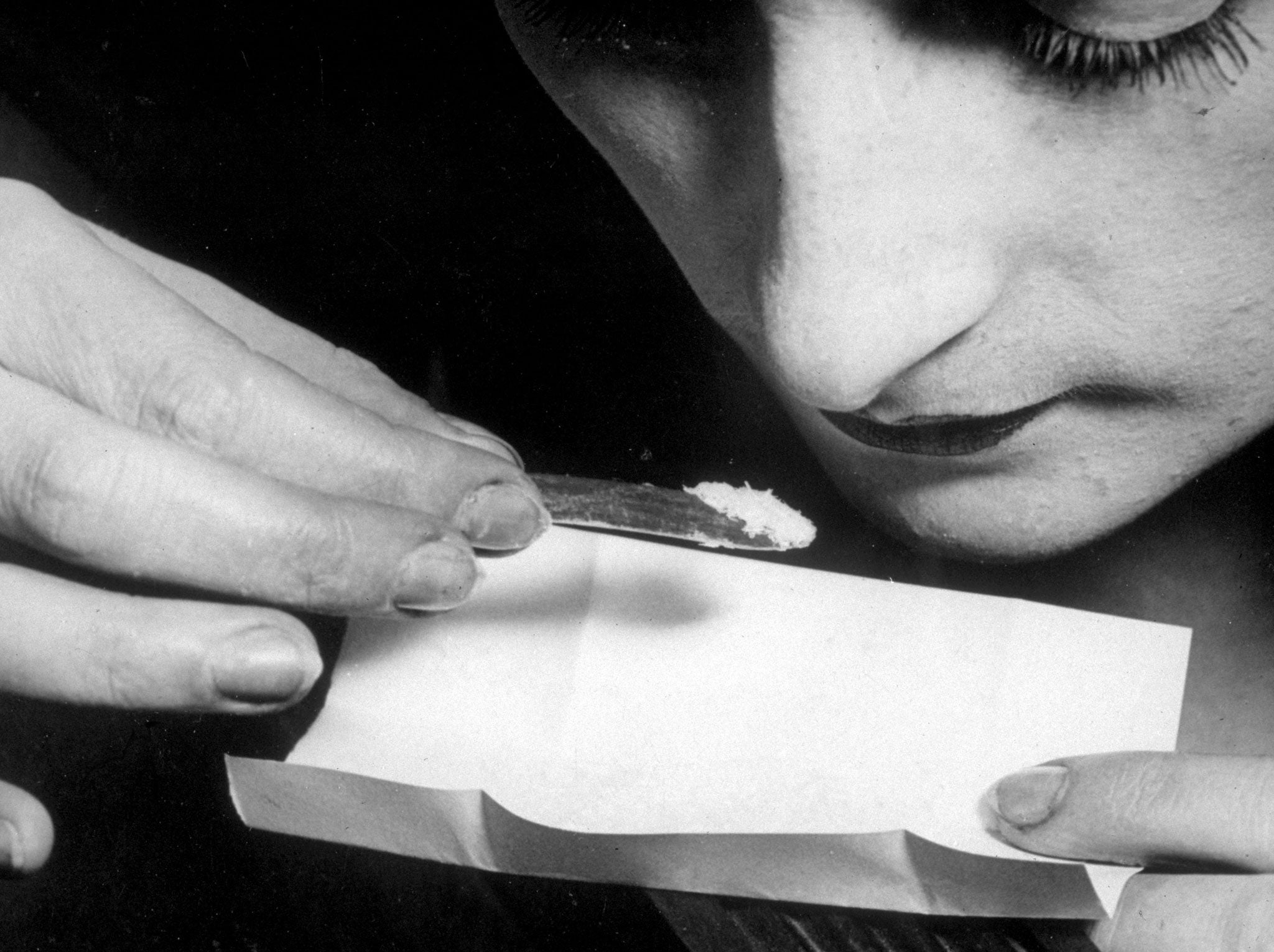

For six months, my time at university crossed over with the arrival of mephedrone, a legal MDMA substitute. Things got zanier in a number of ways. But what was most noteworthy, if we’re being sociological, was the almost total disappearance of any taboo over drug-taking. The fact that mephedrone looked quite a lot like cocaine, and seemed to produce a similar effect (down to the facial calisthenics), didn’t appear to put a whole lot of people off. Instead, an entire cross-section of university life – bookish types, jocks, David Guetta fans – could suddenly be found of an early AM having similarly inane conversations about how much they just adored poetry, each other, or David Guetta.

Other people will no doubt remember things differently. But thinking back on it, these six months - before the drug was banned – rattled my identikit liberal mindset.

For one, I did a double-take on legalisation. While tabloid coverage of the mephedrone craze focused mainly on the risk of death, the less extreme side of the story – that people who wouldn’t have touched illicit chemicals began hoovering up legal ones with gusto – went largely unreported. (In Bristol, the drug was so mainstream a tall man wearing a large cardboard sign saying “mephedrone dealer” wandered into local folklore).

It’s true that the hothouse lifestyle of university campuses is hardly the wisest place to conduct experiments with legalisation. Nor is it the most representative. Nonetheless, after the radical unwiring of one or two people I care about, and the widespread normalisation of drug culture, I’d be wary of any attempt to decriminalise our current crop of so-called ‘psychoactive substances’.

The “war on drugs” has failed, and cataclysmically. Perhaps legalisation remains the best solution for society as a whole – but, at least through my anecdotal periscope, it won’t result in nirvana. British people like to boogie, and aren’t too good at stopping.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments