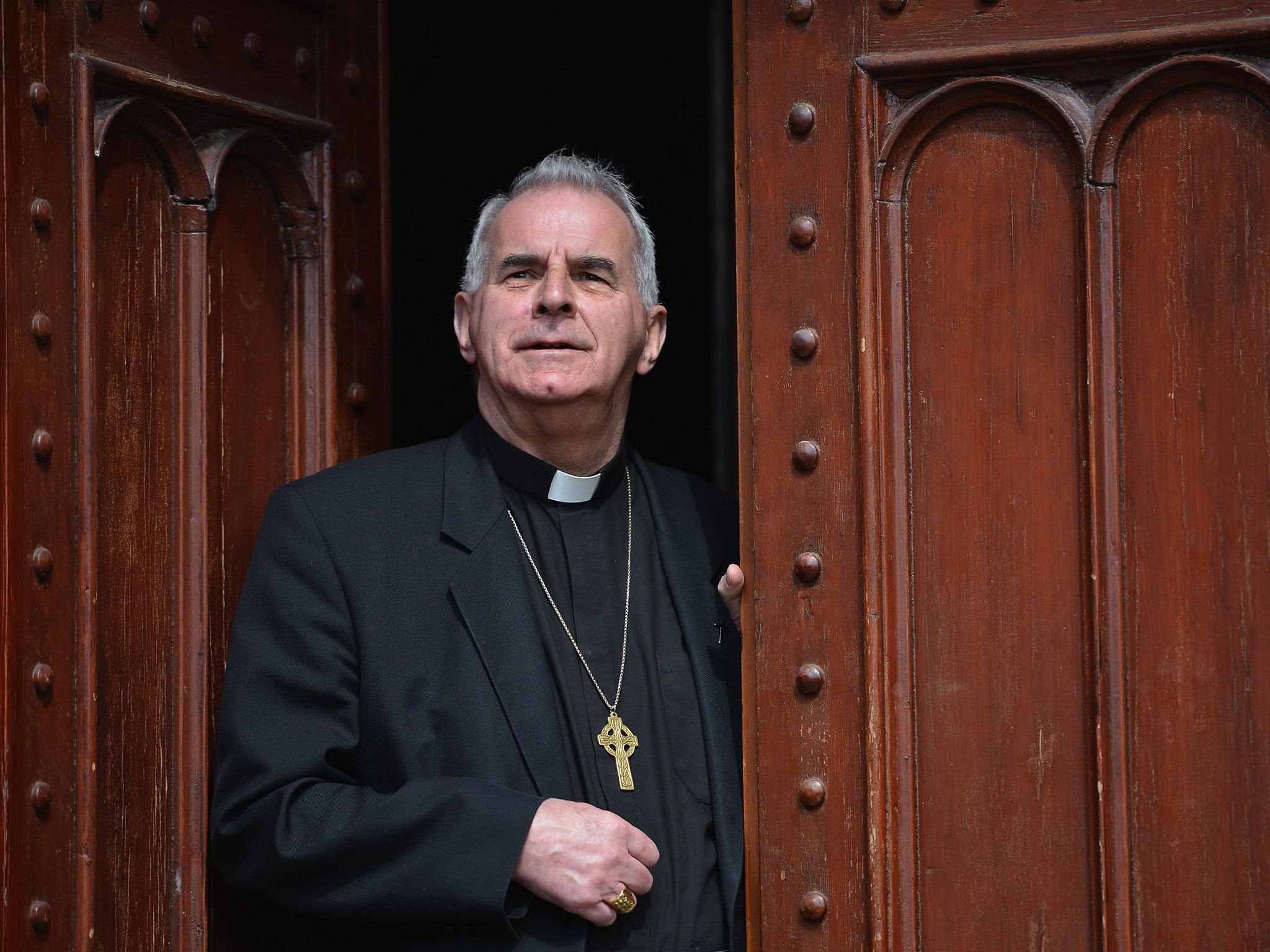

Laugh at Cardinal Keith O'Brien, but not his victims

Plus: If an Ivon Hitchens painting can fetch a six-figure sum, the long-expected crash in the value of art looks a long way off

Tempting as it is to jeer at Cardinal Keith O’Brien, I think we should probably exercise some elementary charity here. The claim that he not only groped junior male members of his institution, but also, according to one anonymous gentleman, was in a long-term relationship with him does seem unfortunate. The cardinal was recently pronouncing that “same-sex relationships are demonstrably harmful to the medical, emotional and spiritual wellbeing of those involved”. Let us make an effort here, and not burst out laughing.

O’Brien is an old man of 75. If all the claims made against him are true, lust and lechery can only cling to him, in W B Yeats’s words, like a tattered coat upon a stick. He was 42 before homosexuality was legalised in his native Scotland, by which time his lifestyle of lace, denunciation and a quiet grope of a junior priest was probably set in its ways. What was he supposed to do? Come out? It doesn’t seem very likely. It must have seemed very much easier to stick to a position in which he had no problem with gay people, as he said less than 10 years ago, so long as they didn’t “flaunt it”. You know, things like going out to dinner with your partner, or living with him, or going on holiday, or ever mentioning his name.

Well, people are allowed to live their lives however they want. If O’Brien had just decided that he was going to hide the elementary facts of his life from everyone, and if the person he was, it is claimed, in a relationship with had decided that he, too, was going to exercise that degree of concealment, who would care? It was once necessary; for many people, the concealment continued through habit. That is the right of individuals.

But through a familiar quirk of personality, Cardinal O’Brien was drawn to comment on an ineradicable part of his own personality. One can well guess what the process was. Someone hates and fears a forbidden aspect of themselves, and is drawn ineluctably to talk about it, rather than remain silent on the subject. Foucault wrote an interesting series of books about the history of sexuality, in which he proposed that the 19th century placed a prohibition on sexuality, not to silence discussion of it, but so that they could go on talking endlessly about it. Similarly, O’Brien clearly suppressed public knowledge of his own sexuality so that he could go on talking indefinitely about homosexuality. Going on about how awful those gays are – that, I am afraid, counts as “flaunting it”.

One can guess what damage O’Brien did to his own personality, but that is really no business of ours – he entered into the processes of self-damage freely. We can give him the benefit of the doubt, and think that the gentleman who, it is claimed, was in a long-term relationship with him conducted the relationship consenting to the limitations. But O’Brien used his position to damage lives.

There were the junior colleagues who were subjected to predatory approaches which were possible only from positions of secrecy. There were people around who may have learnt the lesson that it is all right to be attracted to men, so long as you conduct it in total secrecy and denounce people like you in public. There are an unknown number of people whose lives were made more difficult and humiliating by the fact that a cardinal, when he speaks, is listened to by simple people, and believed.

What good, really, is brought into the world by the insistence that consensual, equal gay relationships damage the health, emotions and spiritual well-being of those involved? Encourage gay people to marry people of the opposite sex? Or live in denial and habits of secret predation? Or accept that they will never love or be loved? Oh, yeah, that’s going to improve the world.

I would have great sympathy for Cardinal O’Brien, if, like other ancient closet cases, he had just kept quiet and destroyed his own life. Self-destruction is never enough, however; the habit has to spread, and spread, like lies, until the solitary queen stands in a blasted wasteland, aghast and conspicuous. For O’Brien’s victims, we can spare sympathy and concern. For him, even given his age and the misery of guilt, shame and terror he must have lived through, I think we can raise an eyebrow, shake our heads and laugh a little at human folly.

That’s what I call a leaving gift

Dame Marjorie Scardino has retired as chief executive of Pearson, the publisher of the FT, among other things. They have very kindly given her not just a socking great £6m in her final year, but an Ivon Hitchens flower painting that Dame Marjorie had hanging in her office.

I’m sure she deserves it, but the astonishing thing was what the painting is now said to be worth. It was credulously stated by newspapers that it would sell for between £50,000 and £100,000 at auction. Hitchens, who died in 1979, was a likeable but by no means major painter. The work was bought for £12,000 in 1988. Then, and now, are exactly the moments when one would normally expect to see a posthumous decline in the value of an artist’s work. Instead, it is climbing steadily.

It is so much easier now to track the value of art sold in auction that it has a stronger tendency to sustain its value. It can be proved to be an investment, and so fulfils the prophecy. This is what is bafflingly delaying the long-expected crash in the work of Damien Hirst. It hardly matters how many hundreds of spot paintings he produced – it can be demonstrated that they hold their value. Of course, in the end, artists will collapse like Burne-Jones in the 1930s. But for the moment, an artificial mechanism is keeping prices up in the air, and an unremarkable but pleasant flower painting by an unfashionable painter would go for a six-figure sum.

My dream of snapping up a Cy Twombly or a Francis Bacon when the fashion for their work fades seems as remote as ever, and nobody on my retirement is going to hand over even an Ivon Hitchens.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments