The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

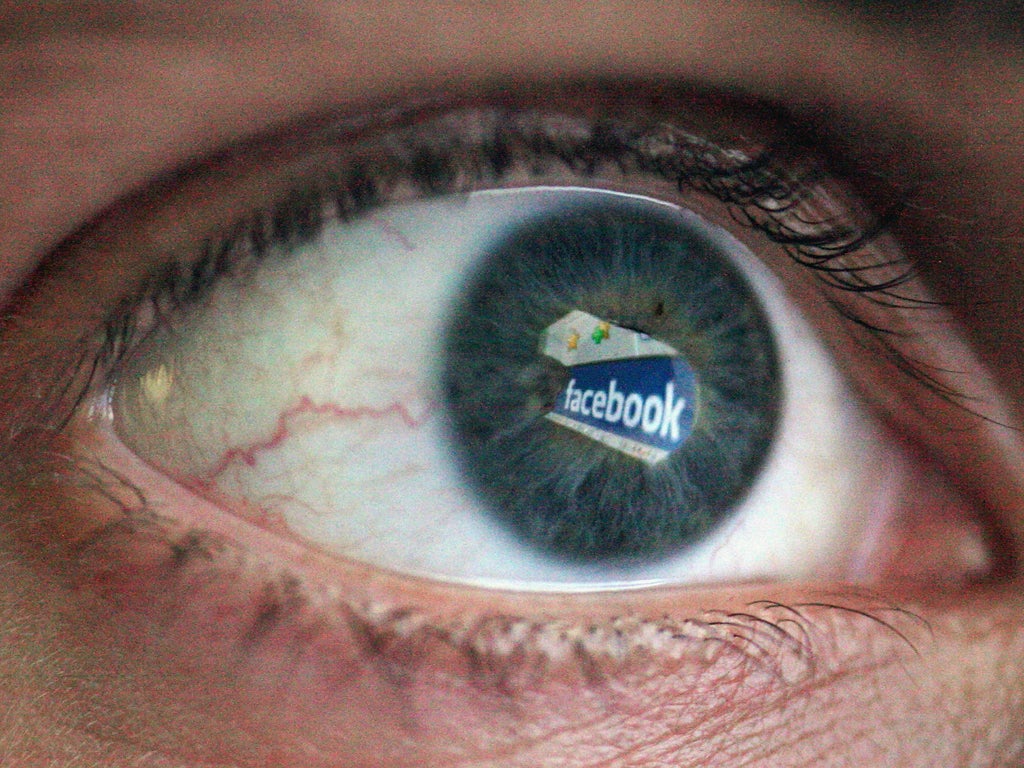

Is Facebook the 21st century confessional box?

Autobiographies, status updates, Twitter - we're all programmed to confess our every move in modern society.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

At 20:43 on the 19th of September, Stuart Bradshaw updated his Facebook status to ‘I’m actually the scattiest person in the world, in one day I’ve lost my passport and my sunglasses’.

Why bother posting this? Who actually cares? Stuart’s friends were obviously thinking along the same lines: out of over 1,500 of them, only four (that’s less than 0.3%) responded. Still, Stuart regularly makes similar posts about his day to day life, and he’s not alone – there are 293,000 status updates every minute on Facebook.

Now I know that not all these updates are as dull as Stuart’s. But over the course of a single day, there’s sure to be a few hundred thousand or so along analogous lines. The question I’m wondering,, is why people write these statuses, when the overwhelming majority of their readership clearly (and rightly so), couldn’t care less?

To try and answer the question, I began collecting Facebook statistics. I learnt a few fun facts: of the 900+ million Facebook users, 57% are women and 43% men. Women, I also discovered, have an average 55% more posts on their timelines than their male counterparts. I also found a brilliant little site that gives you a free personalised analysis of your own Facebook behaviour. But while interesting, these stats weren’t getting me any closer to explaining the behaviour of Stuart and his ilk. The eureka moment came (as usual) out of the blue, when I stumbled across a link that led me to Ovid’s 2000 year old story of King Midas and his misbehaving barber.

In the story, King Midas is cursed with an ass’ ears by the Greek god, Apollo. Midas starts wearing a special turban to cover these embarrassing protuberances, and largely succeeds in hiding his deformity from the public. The only person to know is his barber, whom Midas warns that if he tells anyone – is a dead man. But the barber simply has to tell, so he digs a hole in a meadow, whispers his secret, then covers the hole back up. Time passes, reeds grow over the hole, and when the wind blows, they whisper the barber’s confession: ‘King Midas has an ass’ ears!’

Now, I put it to you, that the compulsion which drove the barber to whisper his secret, is the same thing that drives Stuart’s and billions of other status updates on Facebook: the desire to confess. And by confess, I don’t mean it in an ‘it was me – I admit it’, sense. I mean it in the O.E.D. sense of ‘to make one’s self known’.

In a way, it makes sense that confession in the 21st century should take place on social media sites like Facebook. In Western countries, the majority of us no longer utilise the confessional practices of organised religion, but the human need to give of ourselves is still there – so why not do it through a medium we’re more familiar with? This seems to have been the thinking behind ‘Confession: A Roman Catholic App’, launched by a trio of Americans last year, which takes users through the Ten Commandments, an examination of their conscience and any custom sins they might have, then wipes the slate clean. The app was a huge hit, reaching No. 42 on the best-selling list last year, according to iTunes.

It also makes sense for social media to be our confessional platform given the large audience it provides. We tend to think of confession as something private, between ourselves and our priest/best friend/therapist. But in reality, 21st century confession is just as likely to be a public affair. Some of our most watched shows –The Oprah Winfrey Show, Jeremy Kyle, Jerry Springer – turn the act of confession into a worldwide event (Oprah’s top viewing figures reached 90 million for one show). And it’s not just television. Walk into Waterstones, and the number of autobiographies like Claire Balding’s My Animals and Other Family (and what is an autobiography if not an enormous confession?) is astounding. There’s also the routine ‘confessions’ in the likes of hugely popular magazines like Hello and OK! The act of confession has become a public event, both encouraged and perpetuated by Facebook, Twitter, and the blogosphere.

So, is this a great or terrible thing? There is little doubt that confession does have the cathartic ‘feel good’ factor of getting something off your chest. Professor Jeremy Tambling of The University of Manchester also makes another important point: confession gives you a sense of importance, of self-worth – you have done something that is worth confessing to. Even if, as in poor old Stuart’s case, all you have done is mislay a few items. Oh, and if you were wondering, he did find his passport. In fact, I’m not sure he ever actually lost it in the first place...

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments