Forget Osborne’s ‘path to prosperity’ – we shouldn’t get too excited about this growth

A quarter of the growth under the Coalition is down to Labour’s Olympics investment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The economy has grown for three quarters in a row. Whoopdeedoo! The Office for National Statistics’ first estimate of GDP growth was 0.8 per cent for the third quarter of 2013. But let’s not get carried away into believing, as George Osborne claimed, that the economy is now on the “path to prosperity” — especially given that this latest burst in output appears to be fuelled by Government spending and consumer debt driven by rising house prices.Net trade and investment show no sign of making contributions to growth, and business lending continues to fall. Plus the latest evidence suggests that both the US and the eurozone are slowing, and there is every likelihood unemployment is set to rise again.

Let’s put this little bit of growth into context: the economy has grown 2.6 per cent over the last 12 quarters, compared with growth of 2.3 per cent over the prior four quarters from Q4 2009 to Q3 2010 that the Coalition inherited. Not only that, but around a quarter of the growth we’ve had under the Coalition is down to Labour’s investment in the Olympics. Output still remains 2.5 per cent below its starting level of output, five years in. There is every chance by the May 2015 election that output will still be below where it was seven years earlier.

Growth of 0.8 per cent was exactly the consensus among economists who were polled for their forecasts, but it was well below what was implied by business surveys. The UK all-sector PMI hit a new record in August. Markit suggested the data “put the economy on course to expand by at least 1.0 per cent and possibly as much as 1.3 per cent”. Other surveys including the Bank of England Agents’ scores and the European Union business and consumer surveys have also signalled a pace of expansion much greater than most policymakers have been expecting or as actually observed in the hard data. I am a big fan of these surveys, which most academic economists don’t even know exist, and not least because they provided an early warning alarm of what was coming in early 2008.

Qualitative surveys also have the benefit that they don’t get revised, as the GDP figures do. One possibility is that the GDP data will be revised up, which would make the two more consistent but that is unlikely given the average revision over the last 25 quarters has been minus 0.1 per cent a quarter.

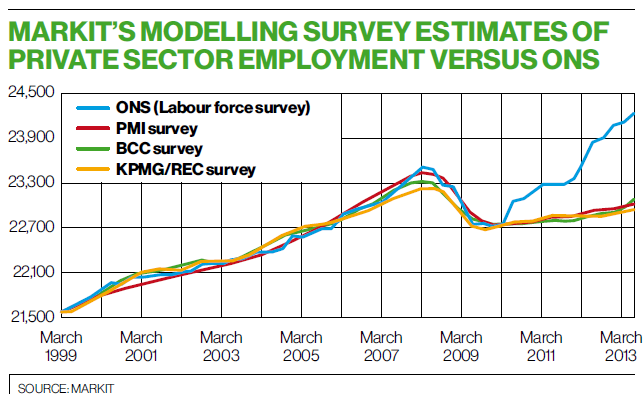

An interesting note published last week by Markit’s Chris Williamson suggests that over the last three years there is also a major discrepancy between the number of private jobs reported in the UK by the Office for National Statistics compared with the much lower number of jobs reported in the business surveys. This is of particular note because ministers such as Sajid Javid and George Osborne have trumpeted the huge success the Coalition has had in creating millions of private-sector jobs. Not so fast, Mr Williamson says. The true job creation number may well be less than a quarter of that. Indeed, one of the surveys based on job hiring suggests the official numbers may be seven times too big.

The ONS calculates the number of private sector jobs from the Labour Force Survey, but in doing so makes adjustments for the fact that approximately 250,000 workers in the Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds were moved from the private sector to the public on 13 October 2008 as well as 196,000 further education college and sixth-form lecturers who were moved the other way in March 2012.

Between June 2010 and June 2013, the number of private-sector workers rose by 1,168,000 (noting that the June data relate to May to July, which is probably the appropriate place to start given the coalition was formed on May 11, 2010), which means this starting date includes a couple of weeks of job creation more appropriately attributed to the previous Labour government.

Mr Williamson made use of three business surveys — the purchasing managers indexes (PMIs); the British Chamber of Commerce quarterly survey (BCC) and the KPMG/REC survey of job hires, also conducted by Markit.

The PMIs cover construction, manufacturing and retail, and exclude agriculture and private household workers. The BCC survey covers manufacturing and services while the REC survey samples job hires through recruitment agencies. Importantly, the three surveys accurately tracked official data prior to 2010.

Since 1999, for example, the PMI survey’s indicator of employment growth across manufacturing, services and construction has exhibited a correlation of 94 per cent against the ONS Labour Force Survey estimates. However, since 2010, the relationships between the ONS data and all three surveys have broken down.

Using the data from these three surveys, Williamson calculated that the ONS’s estimate of a 1,186,000 increase is 921,000 higher than the average of the survey based estimates. Based on the PMIs, private-sector job growth was 258,000, slightly higher at 308,000 using the BCC and only 174,000 using REC. The chart above presents the private-sector numbers. For consistency over time, it adds back the RBS workers and excludes the education workers so that in June 2010 there were 23,057,000 workers compared with 24,225,000 in June 2013.

How to explain such a big difference of nearly a million additional private-sector jobs? A part of the explanation is that the surveys exclude self-employment, which is up 210,000 over this same period; that leaves 710,000 to explain. A further possibility is that the 437,000 public sector workers who lost their jobs over this period have simply been reclassified into the private sector and have not been picked up by the surveys. So there may be an issue about the representativeness of the qualitative surveys. Another possibility is that the Labour Force Survey is overstating the amount of job growth.

The business surveys suggest that output growth has been higher but employment growth lower than the official estimates suggest. These are important puzzles that need resolving. What a mess. The worry is this little burst of growth isn’t going to be sustainable. Watch this space.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments