Farewell Fat Cat Wednesday, will you come along any sooner next year?

How can it be right that an executive can earn a seven figure bonus after a matter of months?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hats off to the High Pay Centre. Fat Cat Wednesday is a great concept. In case you hadn’t heard, it is the day at which the average FTSE CEO had made what the average British worker makes in a year.

It says it all that it occurred just eight days into the new year.

To be strictly accurate we reached that point by the middle of the morning of January 8.

But if the City is true to form it’ll be Fat Cat Monday next year. Or even Fat Cat Sunday.

The Centre, an independent think tank which campaigns to reduce the income gap between those at the top of society and the rest of us, has been arguing that someone needs to tell top bosses that they have had long enough in the sweet shop.

Please note, this is not a party political thing. It’s just common sense. How can it be right that an executive can earn a seven figure bonus after a matter of months, when their impact on a business can be limited at best?

Improving corporate performance requires the work of multitudes of people. If it happens, they should all share in the rewards. But this is rarely reflected in practice. We have allowed a system to develop where those at the top take all the credit and reap most of the benefit.

This is a nonsense. And potentially a dangerous one. Societies with large income disparities in income tend, historically, to be less than stable.

We’re starting to get to that point. According to the Centre, boardroom pay at Britain’s top companies has increased by 74 per cent over the past decade, while wages for ordinary workers have remained flat at best in real terms.

While there’s been a squeeze on pay generally, even relatively stingy companies (and they’re rarities) say they like to pay something close to the “median” average (in other words, they want to be in the middle) to those in the boardroom. No one ever boasts of being in the bottom quartile when it comes to their execs. Or even the bottom half.

That means that top pay inexorably rises. Because every time there is a review, the remuneration consultant says to the remuneration committee (usually made up of current and former execs who either benefit or have benefitted from the system) your chaps need a rise. They are under paid compared to their comparators.

Along comes the next company, and the same arguments are deployed, rises are handed out, and up goes that median again. Even where that median argument is not stated publicly, it’s used in private.

What’s more, if an executive’s basic rises then everything else rises. Bonuses and long term incentives are all either a percentage, or more likely, a multiple of the basic number.

And so it goes, with those at the top snaffling an every greater share of the wealth that is created by organisations.

Efforts to bring some sanity to the process have so far had little impact. Big institutional investors have proved reluctant to use even the advisory votes on remuneration reports that they have. They claim that it’s more effective to make their concerns known behind closed doors.

The Centre’s figures - culled form companies’ annual reports - show just how effective this “quiet lobbying” is. Not very.

And so the telephone numbers get progressively longer. Can anything change it?

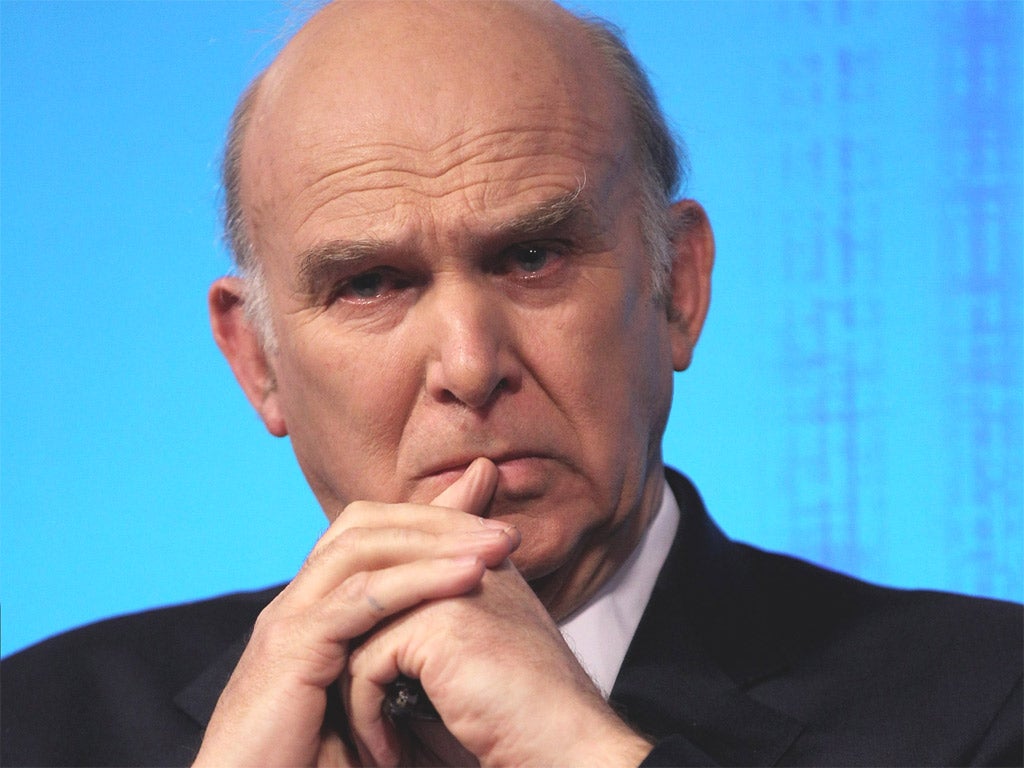

Well, now shareholders have more than advisory vote. Vince Cable has handed them binding votes on pay policy.

So a “no” vote will cause more than just embarrassment. It could force companies to go back to the drawing board when it comes to setting remuneration at the top.

Will it work? We’ll see.

The current pay levels are not in shareholders interests for a number of reasons. It’s not only the inequality that’s problematic, or the fact that the impact a single executive can have on a huge organisation is often grossly overstated.

Making the sort of money that they do means executives have increasingly become divorced not only from reality, but from the customers they serve.

There are a host of other arguments I could call on. You’ve probably read them before. You’ll doubtless read them again when the annual report and AGM season gets into full swing.

The point I’m making here is that shareholders need to use the new power they have been given. The sweet shop needs to close. And if it doesn’t, then Mr Cable needs to take further action. Because it’s just getting silly.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments