England is moving away from Scotland rather than the other way round

One Tory minister from the last parliament has already made a list of what was blocked then and can go ahead now

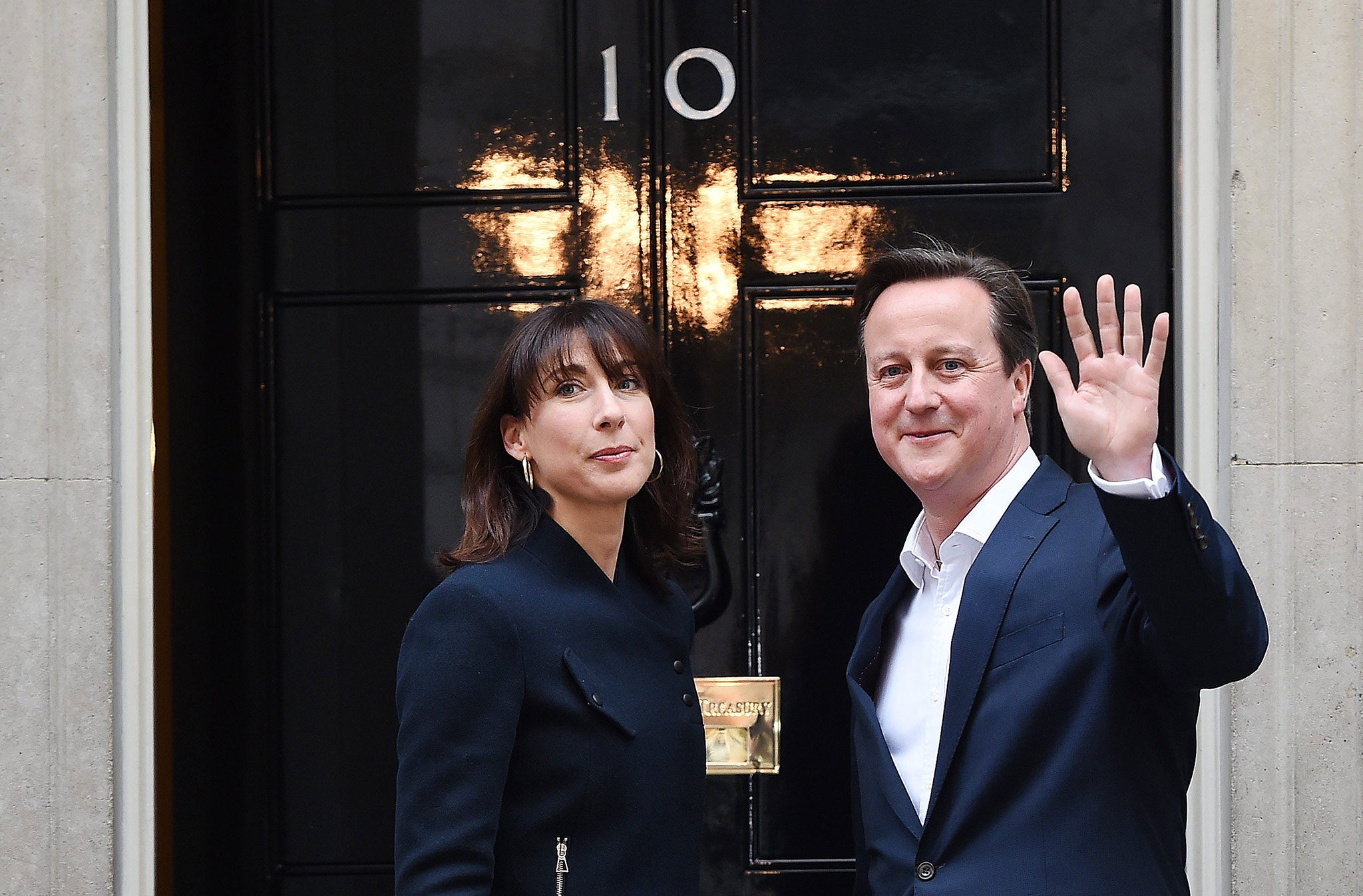

The result was so unexpected it distracts from the wild storms that lie ahead. With endless opinion polls wrongly suggesting a close outcome, David Cameron justifiably claims a big victory. But he has a tiny majority in what will be a febrile House of Commons.

Expectations determine how we view what has happened. Cameron has roughly the same tiny majority as the one Harold Wilson secured in the October 1974 election. Then some polls had suggested Labour would win by a fairly big margin. As a result Wilson was despondent about an outcome that gave his party the same tiny majority that the Conservatives are now celebrating. His despondency proved to be justified, as the fragile Labour government endured a helter-skelter parliamentary ride. Similarly, for all the Tory euphoria, Cameron will feel very fragile quickly. He had a bigger majority when he was Prime Minister of a coalition. No wonder one of Cameron’s first moves was to invite the senior backbencher, Graham Brady, for a cup of tea. Brady and others could cause trouble very quickly if they feel inclined to do so.

But for now unsurprisingly some of Cameron’s more ideological ministerial allies are excited by their unexpected freedom as a one-party government. Already they speak enthusiastically of ruling unleashed. At last their frustrated Thatcherite ambitions can be realised even more fully, or so they hope. Those ambitions include reducing the size of the state, a referendum on Europe, a right to buy and other 1980s echoes.

Nick Clegg made some fatally naïve errors when he took his party into coalition with a party of the radical right in 2010. Nonetheless Clegg’s critics will soon realise how much he constrained some of the Conservatives’ more extreme policies as they are implemented in this parliament. One Tory minister from the last parliament has already made a list of what was blocked then and can go ahead now.

Such zeal explains why England moves away from Scotland rather than the other way around. Scotland has not opted for NHS reforms that are costly and lead to such a convoluted hierarchy of controls no one is quite sure who is accountable to whom. Scotland has no tuition fees. Schools in Scotland are not subjected to the fractured reforms in England that are both acts of centralisation and anarchic. England will move further away unless Cameron means what he said in his gracious victory speech when he advocated vaguely a “one nation” Conservatism. Arguably Cameron has more authority over his party than he has ever had in the immediate aftermath of this unexpected victory. Perhaps he can do what he pledged to do in 2005 and seek to widen the Conservatives’ appeal by moving away from reheated Thatcherism. He has a brief opening to do so.

His authority may be challenged soon. Already current affairs programmes are inviting some of Cameron’s Euro-sceptic MPs to outline their hyperbolic demands for his renegotiation of the UK’s membership of the EU.

Polls suggest that a growing number of voters want the UK to remain in the EU, but a midterm referendum is a risky proposition. If the UK leaves the EU the SNP leadership will probably seek a second plebiscite on independence, an apocalyptic sequence that will make yesterday’s political drama seem tame.

For Labour and the Liberal Democrats there are more immediate hurdles to face, all of them intimidating. For Labour to leap over them without some of its most formidable figures makes the task more daunting. The traumatic shock of defeat yesterday was as great for Labour as in 1992, the last election when the opinion polls were wrong. The setback is even greater. In 1992 most of Labour’s stars survived the electoral wreckage. On Thursday all its heavyweights from Scotland fell. The shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls, also lost his seat. Balls would have been a commanding chancellor. As arguably the third-most influential figure in the New Labour era Balls has already made a significant contribution to public life, but the fall was brutal.

Now Labour’s leadership contenders will have to revive their party without him, Douglas Alexander and other experienced figures, framing a message that resonates in Scotland and England, on the surface at least two very different target electorates. Labour needs to reflect far more deeply than it did in the aftermath of its 2010 defeat.

At least it is still a political force. As a parliamentary party the Liberal Democrats are almost wiped out. Arguably they faced doom from the moment they formed the partnership with a right-wing Conservative Party. Signs of Thursday’s collapse were right in front of their eyes if they had chosen to look, the humiliating lost deposits in by-elections and the bleak poll ratings. For all the talk of multi-party politics perhaps the 2010 Coalition will be seen as a freakish one-off rather than the start of a pattern.

One party rules in Scotland too. The SNP dominates the Edinburgh Parliament and will be players in Westminster. With England electing a Conservative government Nicola Sturgeon has the ideal political context in which to make her next moves.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies