Economic outlook: Britain has exorcised the inflationary demons of our past

Globalisation has reduced workers’ bargaining power around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The big economic news last week was the decision by the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to continue with its asset-purchase program of $85bn (£53.32bn) a month made up of $40bn of Treasuries and $40bn of mortgage-backed securities despite the evidence that the US economy is slowing. It is clear to everyone that the committee was absolutely right to not taper at its last meeting: expectations are that tapering won’t start for some time and if the US economy continues to deteriorate, the next move could be to do more quantitative easing, not less.

There was evidence from the latest, delayed labour-market release that job creation had slowed, with private-sector payrolls up by a less-than-expected 148,000 in September. Slowing in the labour market was confirmed by the latest ADP National Employment Report which again was soft at 130,000 in October, broadly in line with expectations.

Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, argued that “the government shutdown and debt-limit brinkmanship hurt the already-softening job market in October. Average monthly growth has fallen below 150,000. Any further weakening would signal rising unemployment”.

The government shutdown appears to have also resulted in a major hit to consumer confidence; the Conference Board’s consumer confidence index, that had declined moderately in September, declined sharply in October. The index now stands at 71.2 (1985=100), down from 80.2 in September. The present situation index decreased to 70.7 from 73.5, while the expectations index fell to 71.5 from 84.7 last month.

The concern, of course, is that a slowing US economy spills over and chokes off the early stages of recovery we have seen in the UK economy, just as it did in 2008.

Declines in consumer confidence in the US presaged similar declines in consumer confidence in Britain, just a few months later.

Of interest also was the publication by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of real hourly and weekly earnings data in the US which by rose by 0.9 per cent on the year. This contrasts with the UK where real earnings are falling at around 2 per cent per annum. The other number of note was the US consumer price index (CPI) for September which rose by 1.2 per cent on the year compared with a 2.7 per cent rise in the CPI in the UK which is the highest rate of any major Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country (eg. Australia 2.2 per cent; Germany 1.4 per cent; France 0.9 per cent; Netherlands 2.4 per cent; Italy 0.9 per cent; Sweden 0.1 per cent; Greece -1.1 per cent).

So the FOMC is loosening monetary policy with real wages growing at 0.9 per cent with an unemployment rate of 7.2 per cent and a youth (under 25) unemployment rate of 16 per cent. At the same time, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is sitting on its hands with real wages falling at 2 per cent with an unemployment rate of 7.7 per cent which is set to rise over the next couple of months and a youth unemployment rate of 21 per cent. Plus the US economy grew by 6.2 per cent over the last three years for which we have data, compared with 2.5 per cent in the UK. Unsurprisingly the pound continues to appreciate. Interesting.

Over the last year the CPI has been pushed up by government or regulatory decisions and once you take those out inflation is below the MPC’s target of 2 per cent. In its February 2013 inflation report, the MPC estimated that the contribution of these administered and regulated prices in the fourth quarter of 2012 amounted to 0.8 per cent, made up of 0.4 per cent from education due to the tuition fee rise; 0.1 per cent due to electricity, gas and other fuels and 0.4 per cent to “water supply; passenger transport by road and by rail; sewerage collection; dental services; and air passenger, alcohol, road fuel, tobacco and vehicle excise duties and insurance premium tax”.

The other main drivers of inflation have been meat, fruit, vegetables, alcohol, tobacco, electricity, gas and air transport. On the year the price of education is up 21.4 per cent. But some prices have gone down including photographic equipment, housecontents insurance, etc.

When prices of a product rise consumers can switch what they buy; if the price of red wine rises, then buy white wine and so forth. The difficulty arises with basic products like food and fuel as there are no close substitutes. Some price rises can be avoided, including the rise in tuition fees which discourages youngsters from going to college and likely raises the youth-unemployment rate. Most people though are not directly impacted by the tuition-fee rise. The quality of some goods, especially electronics, rise and that improvement is adjusted for using so-called hedonic methods. The reality is that people can’t easily calculate the inflation rate in their heads.

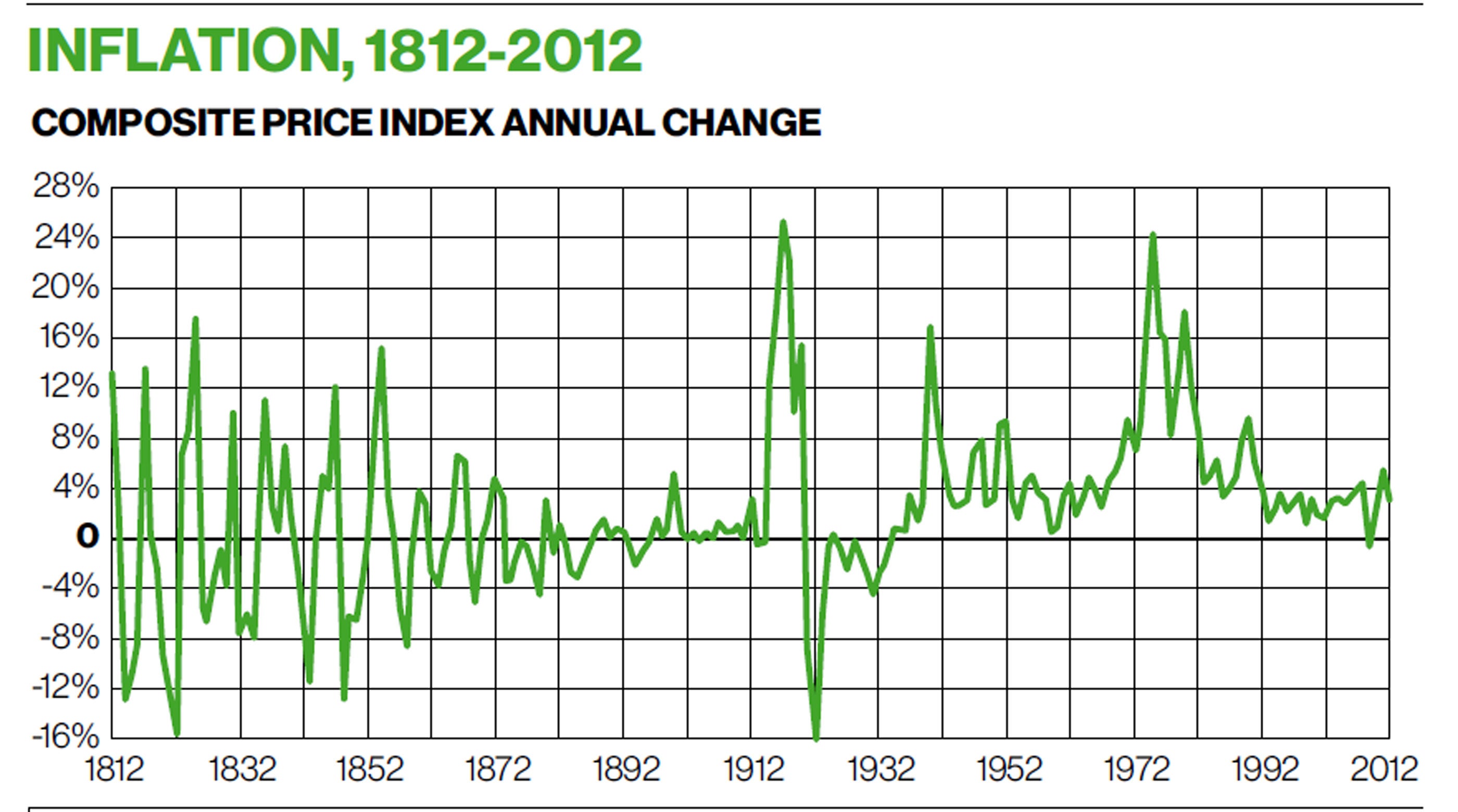

The graph puts the recent inflation experience into historical context. It reports two centuries of data, from 1812 through to 2012 on a composite index constructed by the Office for National Statistics based around the retail price index which is 3.2 per cent currently. It makes clear that the current inflation “problem” bears little relation to the inflation problems of the past.

For the first 100 years of highly volatile data, bouts of high inflation were followed by major deflationary spells. The pre-First World War spike in inflation was followed by deflation in 1921 and 1922. Since then there have been four major spikes hitting a high of 16.8 per cent in 1940; 24.2 per cent in 1975; 18.0 per cent in 1980 and 9.5 per cent in 1990. Deflation occurred in every year from 1921-1933 with the exception of 1925 and then did not happen again until 2009.

It is quite clear that the days of high inflation have gone and Britain has clearly exorcised its inflationary past; this is nothing like the 1970s or 1980s and since 1990 the series averages 3.3 per cent. Globalisation has reduced workers’ bargaining power around the world; union density rates have fallen internationally. Inflation is no longer the great demon, but it is true that energy and food price rises really do hurt as there are no close substitutes. The Government could help, especially with energy prices, but that’s for another day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments