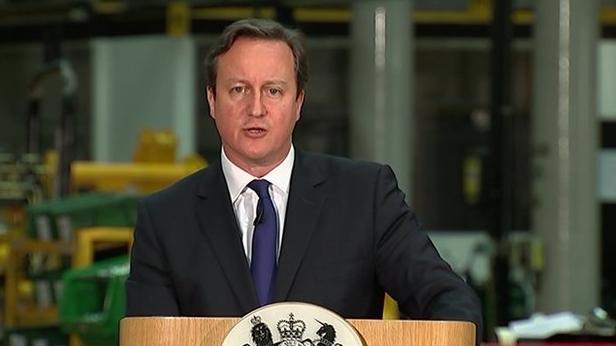

David Cameron’s immigration speech: I broke my promise; this time will be different

The Prime Minister’s speech was brilliantly balanced, but suffered from fundamental flaws

Your support helps us to tell the story

In my reporting on women's reproductive rights, I've witnessed the critical role that independent journalism plays in protecting freedoms and informing the public.

Your support allows us to keep these vital issues in the spotlight. Without your help, we wouldn't be able to fight for truth and justice.

Every contribution ensures that we can continue to report on the stories that impact lives

Kelly Rissman

US News Reporter

This was a speech that tried and failed to bridge the gap between what politicians can do and what people expect of them. It was typical of David Cameron at his best. It was well written, carefully constructed and with a contradiction at its heart. “It boils down to one word,” he said. “Control.”

So it does. That was what he promised on immigration when he became Prime Minister four and a half years ago, and that is what he hasn’t delivered. This week’s figures show that net immigration is running at a higher annual level than that which he inherited from Labour.

So now he is promising it again. “People want the Government to have control over the numbers of people coming here.” And this time they are going to get it – that was the broken message, or the broken-record message, at the core of his speech.

The trouble is that this time round people are more aware of the fundamental problem with such a promise. They know it cannot be delivered while we are in the European Union because of the principle of the free movement of workers. Hence the tricky bit of the argument, much of it iceberg-like beneath the surface of his words.

I will do what I can to restrict free movement as much as possible, he said, without launching a “fundamental assault on the principle”. The two important changes he proposes do indeed shy away from a fundamental assault on the principle of free movement. One is the four-year wait for state benefits that was trailed in all this morning’s newspapers. The other, which he has also talked about before, is to require people from other EU countries to have a job to come to, rather than coming to the UK to look for one. Both of those would make a difference, but only at the margins.

He said in reply to questions after his speech that the “control” he was promising was to “reduce the massive cash incentive for people to come from Europe to this country”. This could be up to – “if they’ve got children – £8,000 a year of in-work welfare”.

This is not what most people think of as “controlling immigration”. It is “influencing immigration”. It is all that a leader who wants to remain in the EU can offer, but the questions come thick and fast. Is it wise to promise to control something that you can only hope to steer from a distance using a system of broken levers and pulleys? How can you enforce a requirement to have a job offer before arrival? Is it humane to deny tax credits intended to keep children out of poverty?

Pro-Europeans may be wringing their hands at this supposed appeasement of the UK Independence Party, but they should notice that Ukip’s success reflects public opinion rather than the other way round, and that it was the Labour Party that started the arms race of extending the period for qualifying for benefits.

Currently, citizens of other EU countries have to wait three months for out-of-work benefits. Labour proposed that it should be six months some time ago and hardly anyone noticed. Last week Rachel Reeves and Yvette Cooper put it up to two years and said it should include in-work benefits such as tax credits and housing benefit. Now Cameron says four years, and everyone agrees that people should not be able to claim child benefit for children who don’t live in this country.

As I say, this was a good speech. It tried to celebrate an open economy and the benefits of immigration, but balance it with the common desire to slow the world down a bit without getting off. The part that was beneath the surface was the argument that the downside of the free movement of workers is a price worth paying for the benefits of the single market, and that if we left the EU we could not be sure that France and Germany would let us back into the single market.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments