Children's TV shows like Grange Hill used to connect us to the real world

The death of Terry Sue-Patt has reminded me of how easy it is now for someone to slip downhill unnoticed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

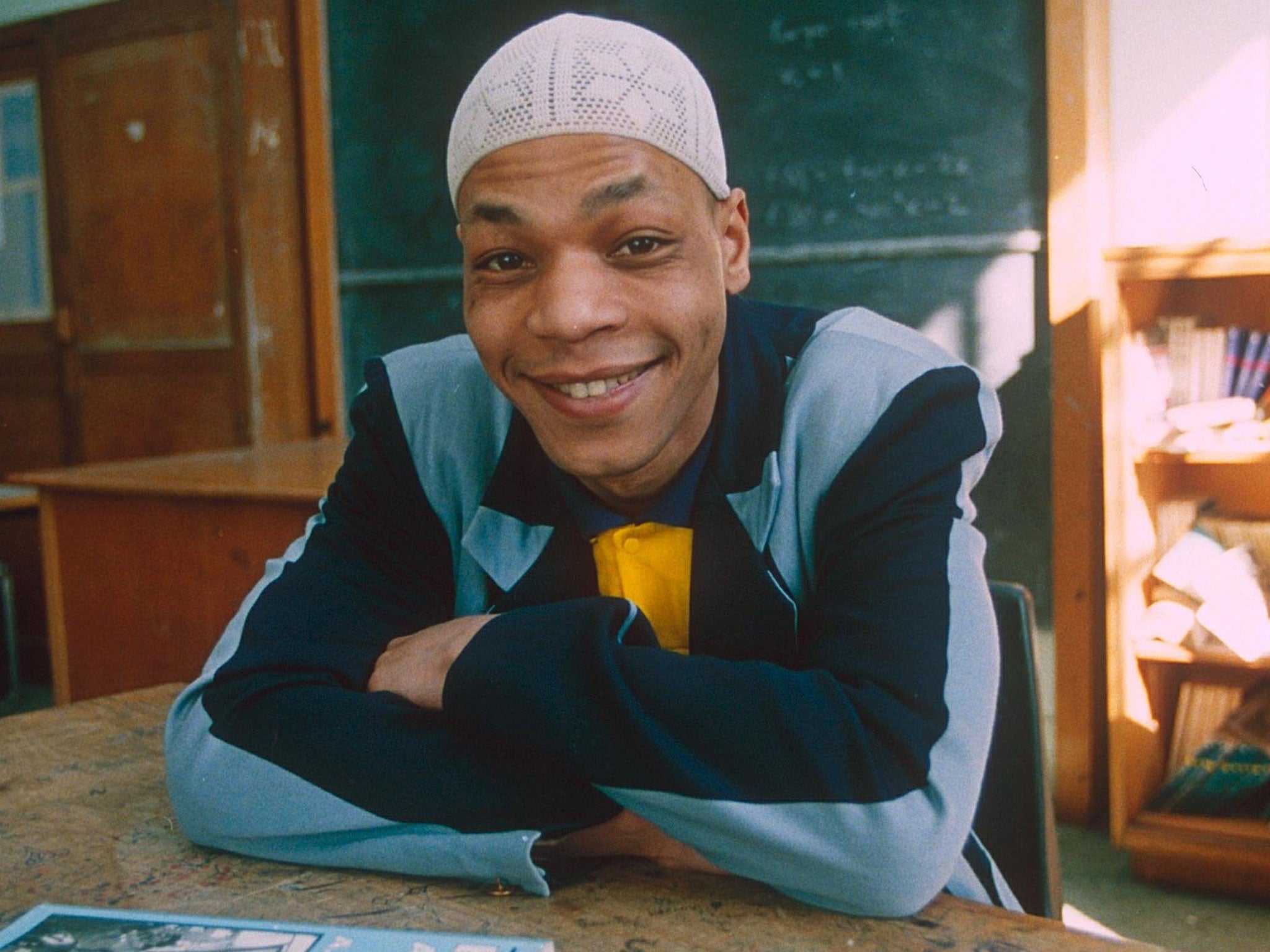

Your support makes all the difference.It was with a sharp and peculiar sadness that I heard of the death of the actor Terry Sue-Patt. I didn’t know him at all, but certainly felt I knew Benny, the character he played in yesteryear kids TV drama Grange Hill. Little Benny who hung about with cheeky and dishy Tucker and loveable lump Alan. Brave Benny who fronted up to vile Gripper Stebson when he was monstering poor Roland.

To me, Benny felt like a good friend I’d fallen out of contact with. The thousands of messages mourning the loss of Sue-Patt which lit up social media this weekend – from Tweeters-of-a certain-age – indicated I wasn’t alone.

Of course, the roaring myth about Grange Hill was that it was heavily controversial, encouraged bad behaviour and was forbidden viewing in many households. This tells us much more about the social class of journalists covering pop culture in the Seventies and Eighties than the show itself.

Yes, perhaps the odd middle-class mother from leafy Seventies Surrey banned Grange Hill before ringing the Beeb, boohooing as a fictional kid with a non-RP accent was gobbing off to a teacher. However, in the rugged North, I never ever met or heard of anyone on a Tucker and Benny ban.

Instead, most Seventies working-class kids were allowed – nay, encouraged – to stare goggle-eyed and unmonitored at absolutely anything on BBC1’s 3.30-to-6pm kids’ slot as long as we shut up, drank our Kia-Ora, and stopped hitting our brothers. Our parents were the first generation to be given television as a free baby-sitting option and took advantage of it shamelessly. Luckily, parent-shaming for not keeping your kid cerebrally stimulated with play dates and after-school Cantonese classes had not been invented.

So we gobbled up Grange Hill, Willo the Wisp and Ivor the Engine. We committed earnestly to the Blue Peter bring-and-buy appeal, ransacking our homes for stuff to sell. We shrieked with glee when Captain Caveman’s power petered out mid-flight during 87 different but completely-the-same Hanna-Barbera scripted tales.

We stared dumfounded when A Flock of Seagulls played synths on Cheggers Plays Pop and we humoured Bagpuss with his narcolepsy issues. It is hard to express the excitement I felt during Friday afternoon’s Crackerjack when Stu Francis handed out cabbages, and I have yet to feel this sort of unfettered joy in adult life.

And, crucially, at a time before iPlayer, YouTube or even VHS recorders, we only got one chance to see these things happen. Miss it and you missed out, so we tried not to miss a second. There was one showing only of Grange Hill’s anarchic “Bring Back Scruffy McGuffey” protest, or Zammo’s overdose, or Danny Kendall’s demise in Mr Bronson’s car.

Grange Hill – with Sue-Patt, playing Benny, being the first boy to walk through the gates – was an attempt to give an entire generation of non-privileged, everyday kids a chance to think about playground politics. They forced us to face up to bullying, racism, sexual awakenings and financial inequality.

Benny, whom we loved for his soft-hearted cheekiness, came from a family with so little cash they couldn’t afford his uniform. He excelled at football, but had no way of buying boots. Grange Hill’s writers gave us tricky dilemmas to get our little heads around. They tried their damnedest to teach us that life is bloody unfair, but with good friends, tenacity and the odd understanding adult, all lives have scope to be better.

I hope Sue-Patt knew the positive part he played in so many childhoods. A very sad footnote to this story are reports that Terry died in his home in Walthamstow and was undiscovered for a month. “He had fallen off Facebook recently and I had begun to wonder if he was OK,” said a friend who had known him for decades.

If Sue-Patt’s death reminded me of much simpler times, it also made me think of today’s hectic, overstimulated world where oversights like this can easily happen. A world where we all – apparently – have dozens, hundreds, thousands of “friendships” which we administer on-line via the dispersing of “likes” to Facebook comments or the sprinkling of red hearts on their latest Instagram picture of a salad. We’ve eschewed the art of unscheduled knocking on each others’ front doors to see if we’re coming out to play, or fancy a coffee, although, ironically, as a human race we’ve never been more connected.

But in the current social climate it is perfectly feasible for a friend to be slipping downhill quickly while maintaining a presence online that says everything is business as usual. “But I heard from her last month,” one might say with a straight face. “She liked my picture of pasta and left the comment, ‘When iz Wine o’clock pls?’ so she must be fine.”

And even if a friend did “fall off” the internet, well, did you really know them anyway? Or was it someone you met in Croatia at a forest rave in 2005 who you mainly follow on Facebook because they have a lot of arguments with people and you can’t quite stop looking? Do you have their telephone number? Would you pick up that number and be as potentially intrusive as to call if they stopped posting? Would you demand to see them with your own eyes?

A lot of things– in fact, almost everything about the Eighties – were worse than they are now, but the art of friendship was not. After I watched Grange Hill back then I would walk out into the street, look my friends in the eye and say directly to them: “Did you watch Grange Hill? It was brilliant!”

It was similar to pressing like on Facebook, but in this case I actually meant it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments