Cameron and Chakrabarti treat press freedom as sacred, but aren't some things more important?

Whoever believes freedom loses its essential character the minute it admits impediment of any sort is in one sense right and in another dangerously insane

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Let’s begin with a big question. “For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” Should the relevance of this not be immediately apparent, please substitute “freedom of the press” for “whole world”. “For what is a man profited if he shall secure the freedom of the press, and lose his own soul?”

We are temperamentally suspicious, in this column, of absolutes. “Democracy”, “liberty”, “human rights”, “freedom of expression” – invoke any one of these in the appropriate company and it’s tantamount to uttering the holy name of God. Except that God’s name does not carry the solemnity it once did, whereas “freedom” – coupled with whichever activity is most dear to you (freedom of thought, freedom of passage, freedom to ride a bicycle on the pavement, freedom to carry a gun, freedom to publish pap) – goes on gaining in righteousness.

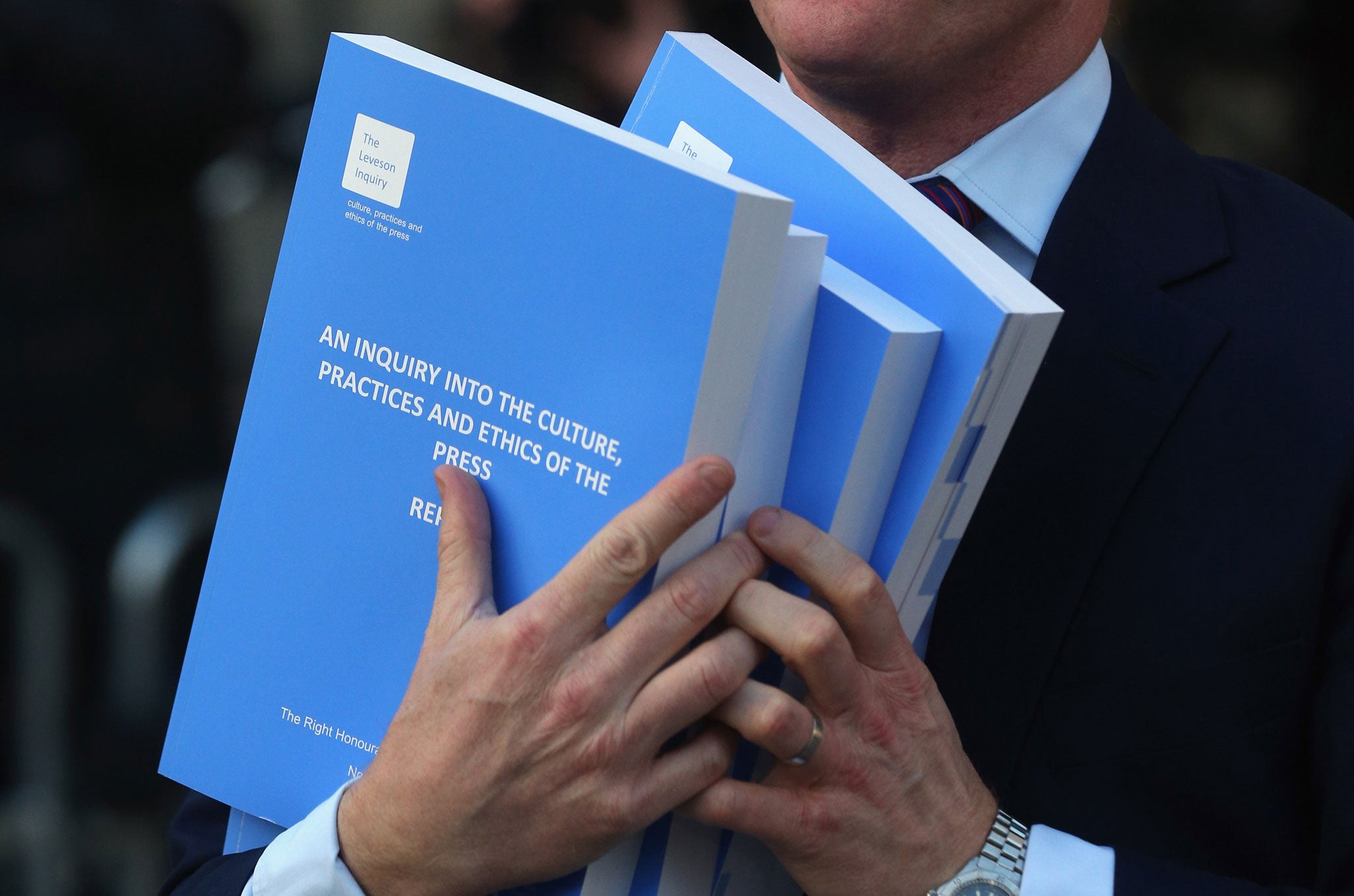

Freedom acquaints us with strange bedfellows. Is that Shami Chakrabarti I see sharing a pillow with David Cameron, no matter that when we last saw her she was under the duvet with Lord Justice Leveson? There are, it would appear, more positions for the lover of liberty to adopt than you’ll find in the Kama Sutra. Take Cameron himself, one minute enjoying cosy text relations with Rebekah Brooks, the next setting up a commission to inquire into precisely such intimacies, now rejecting it, now telling others to sort of accept it, otherwise... well, otherwise something. Freedom, thy name is Inconstancy. Or should that be Opportunism?

Cameron has warned that to accept Leveson is to cross a Rubicon. So? An ominousness attaches to the Rubicon, as though to cross it is to take not just an irrevocable decision but a disastrous one. In fact, Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon was crowned with success. When Caesar approached the Rubicon, Suetonius tells, “He wavered much in his mind... at last, in a sort of passion, casting aside calculation, and abandoning himself to what might come ... he took the river. Once over, he used all expedition possible, and before it was day reached Ariminum, and took it.”

To cross the Rubicon, therefore, in its original application, is to take a risk and achieve your goal. So if we are to talk of Rubicons, Prime Minister, why not let precedence be your guide, and cross?

If the answer to that is a simple “because once you do, there’s no going back”, it has to be asked what we would want to go back to. We did not, after all, much like the scenery or the wildlife on the bank of the Rubicon we’d be leaving. But if the answer is that crossing will shackle the press for ever once we’ve dragged it to the other side, then why was Leveson, whose military campaign this is, so thundering in his warning that no such shackling should be permitted? Is there no statute so subtle, no judicial overseeing so light, that it cannot allow for most of what we mean by freedom and will make its presence felt only when there is nothing to be gained, and everything to lose, by its remaining silent? If you baulk at that on the grounds that “most of what we mean by freedom” isn’t freedom, then we are, I grant you, in trouble.

Whoever believes freedom is absolute and loses its essential character the minute it admits impediment of any sort is in one sense right and in another dangerously insane. All absolutists are pathological. The wise man knows that even when the goal is freedom, certainty is oppressive and completeness a chimera; only fools and tyrants believe in unconditionality.

In every practical aspect of our lives, we accept a necessary imperfection: it’s a free country until the exercise of our freedom interferes with the exercise of someone else’s; we are free to say what we like unless what we say is an incitement to slit throats or throw bombs; we are free to follow our passions and our hearts until the pursuit of either leads us to the unwilling or the under-aged. At which point – and we are likely to have enjoyed an immense amount of liberty before it’s reached – some authority higher than the individual, but ideally encompassing the best interests of all individuals, steps in. So why should the press alone be subject to no authority but the authority of itself?

Freedom matters to the degree that it contributes to the betterment of humanity. Therefore, our welfare must always trump it. However noble Voltaire’s willingness to die so that you, reader, can say something he disagrees with, it is self-defeating to choose extinction over censorship. Citizens of a civilised society weigh principles against practicalities, making choices of which the rigidly principled can be relied on to disapprove. This being a civilised society, we are right to measure the benefits of a free press, which are without doubt considerable, against those intrusions into liberty (freedom is nothing if not paradoxical), those infractions of decency and truth, the wolfishness, the bullying, the monopolising, the pocketing (of men as well as influence), the contempt posing as egalitarianism, the grossness, the sneering, the nihilism, which triggered the Leveson Inquiry in the first place.

At the last, “What does it profit us?” is the only useful question to ask. What does it profit us that we gain press freedom, but suffer a daily diet of sensationalism in which the feelings of the innocent or the marginal are trashed? What does it profit us that the press perpetuates a cynicism that distorts every motive but its own; that dirt-digging alternates with flag-waving to the end of fuelling low curiosity and fatuous nationalism; that a crude, comic-book dependency on the worst that television has to offer trivialises still further the minds of those already mired in it – reader, what, at the cost of losing our souls, do these profit us?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments