The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Bill Gates, impact evaluation, and why anxiety is a catalyst for more effective social change

The ex-Microsoft CEO says measurement is key to "improving the human condition"

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A man named among GQ’s “15 worst dressed” in tech, who once matched a polo-neck with a diamante blazer, Bill Gates nevertheless – in matters outside of fashion – has a sharp eye for the zeitgeist. A computer on your desktop? That’s a Gates trend, from the 90s Microsoft era. Moguls pledging $1bn plus to charity? That’s a more recent Gates-led vogue. Now the world’s number one philanthropist – speaking as chairman of his eponymous and hugely influential charitable foundation – has picked a further trend to back. Measurement. Specifically, the scientific evaluation of programmes designed to tackle tough social problems.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal this weekend Gates notes “how important measurement is to improving the human condition”.

He talks of making sure money given in aid has a significant impact, of measuring its effects on the target population through extensive tests. Much as it might sound like a no-brainer, eulogising data in this way is in fact the tip of a controversial and relatively new area for humanitarian interventions. Previously, do-gooding had something of a hit-and-hope mentality. Gates’ op-ed follows a period of rapid change, in which the NGO community, led by the Against Malaria Foundation and GiveDirectly, has been falling over itself to move away from “qualitative” reporting – pictures of smiling healthy children with a quote or two – to “quantitative” data-fronted reports, sturdy enough to convince business-people (and government) that good intentions are being matched with good outcomes.

More than a punt

This shift is profound, and runs parallel to a similar transformation in Western governments. Under President Obama’s watch “evidence-based policy” – i.e. making sure your vastly expensive teaching programme is more than a punt - has jumped up the agenda: from 2014, policy initiatives signed off on by the treasury will have to be supported by evidence. Same goes over here. Former Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell (known as “GoD”) set up the Behavioural Insights team in 2010, a unit whose MO is heavily reliant on trials and pilots, and whose task is to “nudge” citizens to do things they might not naturally want to, like pay fines.

To people who have fallen out of love with politics, but still feel passionate about large-scale social change, news of these measurement efforts is like a siren-call. Instead of having to put faith in politicians’ or aid workers’ promises - knots that so often disappear when tugged - the impersonal force of numbers, of calculated success in transforming lives, can be put on a pedestal. Ideology gets defenestrated. In its place arrive cold hard facts and a “talk to the spreadsheet” mentality.

There are of course drawbacks. Before getting to them, however, two examples of impact evaluation – one from government, the other foreign aid – show why excitement levels currently run so high. The Nurse Family partnership has been operational in America for almost forty years. It assigns midwifes and nurses to low-income and vulnerable mothers for a period of two years. The results – measured over decades by “the strongest study design” possible – show that children whose mothers benefited from the programme are 58 per cent less likely to have been convicted of a crime by age 19. They also demonstrate a 5 to 7 point IQ boost. Britain is now running its own randomised trial of this programme, with results to be announced in 2013. Interested spectators shouldn’t have to cross their fingers too hard, given the successful replications throughout America.

A stats-heavy approach to change has been put to work in the developing world by groups like Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA). Gates writes in his op-ed of how, “if I could wave a wand, I'd love to have a way to measure how exposure to risks like disease and malnutrition impact children's potential”. A wand is hardly necessary. IPA highlight how de-worming children in schools in Kenya, killing the parasites that steal the nutrients from their stomachs, reduces absenteeism by 25 per cent and leads to higher earnings in later life.

But onto the misgivings. Paradoxically, success has proved a double-edged sword. With their measurably high impact, some worry that programmes like de-worming and the Nurse Family partnership will attract a disproportionate level of funding, leaving others with less easy to quantify results in the cold. A focus on numbers may lead to an emphasis on “easy-wins” - it being a lot harder to show numerical success dealing with the chronically homeless, say, than school-children, whose academic progress is monitored and marked over the years.

The debate will go on. But in the long run, more numerical accountability for social initiatives can only be a good thing, for two reasons. First, it should decrease the risk of waste (evaluations show that all but one of ten major US federal initiatives to help the needy have modest or no impact). Second, it should make governments and charities more responsible to the people they’re trying to help – boosting trust in the organisations themselves.

The right kind of worry

When I worked for London-based NGO Greenhouse, the first time I saw anxiety grip my boss, a ferociously competent former Teach First executive, was during the week before results of an impact evaluation came in. (“Will we see the right figures?” he asked “Are we working with the right kids?”). Professional fear and anxiety are emotions that can be absent in third sector workers. They are also the kind of emotions that ensure, as in the culture of high finance, standards do not drop.

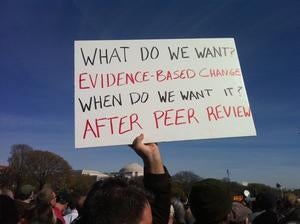

It’s worth closing on a comparison. Before the 1960s drugs and medical treatments did not have to go through a particularly strenuous series of tests. Peer-reviewed literature, randomised control tests and other bulwarks against malpractice were yet to become an essential part of medicine’s framework. Now, the idea that any drug could come to market or be tried in hospitals without exhaustive proof is difficult to imagine. Social programmes will never be measured with the same level of objectivity – there are simply too many variables – but a future where humanitarian work is rigorously evaluated will unquestionably be a better one.

And so long as Bill Gates is in the vanguard, he can dress in as many lemon-yellow jerseys as he pleases.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments