Autumn Statement: History shows we can't tax any more so go figure: the only way is more cuts

Our Chief Economics Commentator says there is evidence that the Chancellor may be learning on the job, but the hand he has been delivered remains very poor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So, according to the Chancellor, Britain’s long march is going to take a year longer. I’m afraid it is worse than that. It is going to take at least a decade longer. That is because though the underlying budget deficit may, if the projections are right, be cleared by 2018, the general downward pressure on public spending will continue long after that.

The reason is that debts built up over the past few years – and being added to every minute – will not be cleared until well into the 2020s, unless the governments of the day decide somehow to write them off, that is to say steal the money from savers.

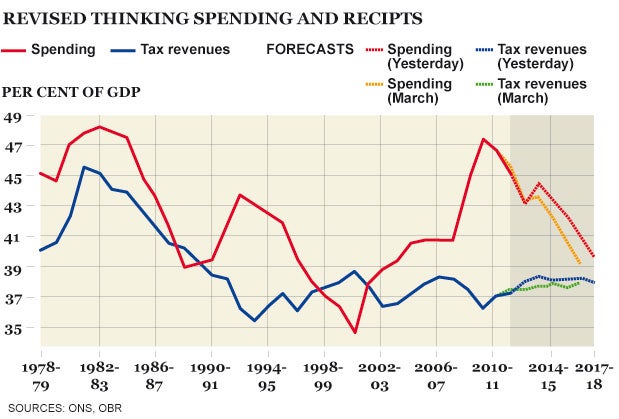

The best way to get one’s mind round what’s happening is to look at the graph above, taken from the Office for Budget Responsibility’s new report. It goes back to the days of the Labour government that fell in 1979 and shows what has happened to public spending (the red line) and tax receipts (the blue line) since then – both expressed as a percentage of GDP. As you can see, the present squeeze on spending runs on longer than was expected last April and the tax take is a little higher.

Come back to that in a moment but, meanwhile, note something else. Tax revenues have been stuck at 38 per cent of GDP since the late 1980s, a generation. Unless you believe that that tax take can be ramped up to the levels they were at during the early years of the Thatcher government, when they were boosted by high North Sea oil revenues and privatisation proceeds, that is what the Government has to play with. But the things governments have to spend on will inevitably rise.

As the country ages there will be more pensioners and higher medical costs. Worse, the government will probably find itself going into the next recession, whenever it comes, with double the debt that it went into the last one. So the squeeze on the rest of government spending will go on, and on, and on. Note that on these figures, public spending will still be higher as a percentage of GDP in 2017 than it was in the early years of Gordon Brown as Chancellor.

So what else can we learn from the great mass of new data?

The forecast first. The OBR has produced a thoughtful, subtle piece of work. Gone are the days when any economic forecaster could produce a set of numbers and expect them to be believed. The OBR wisely acknowledges both the puzzles about the state of the economy now and the uncertainties it faces in the future. The greatest puzzle is the strength of employment, with half a million more jobs now than expected back in March. Half of that increase comes for the self-employed and part-timers but half is full-time. As a result, unemployment is 7.8 per cent against an expected 8.7 per cent. Against that, growth is much worse, with the number this year being minus 0.2 per cent against plus 0.8 per cent.

If there is such uncertainty about the present, think of the uncertainty about the economy three or five years out. The OBR thinks the economy will gradually pick up towards its long-term trend growth in the next few years. If it does, the Government’s finances just about come back on track. If not... well, let’s not go there.

It is a difficult hand of cards to play. If you accept that the macro-economic background is pretty much set, the Chancellor’s room for manoeuvre is minimal. Some believe he should simply borrow more but the plain fact is that every government of every large developed nation is cutting its deficit. Ironically, by rolling things back he has ended up with a deficit-cutting profile that is similar to that proposed by his predecessor, Alastair Darling.

The more telling line of criticism is that he, and indeed the Coalition as a whole, has been getting the detail wrong. Here there are signs that he is learning on the job. On the tax side he has started to focus on tackling evasion, while bringing down business costs. On the spending side, the switch towards investment will have a marginal but welcome impact. Other schemes by the Government, such as those designed to boost investment, are welcome too. But the numbers remain terrible and will continue to do so. All we can hope for is reasonable competence in handling a very difficult situation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments