The pound has hit a 31-year low – it's time to accept that Brexit will definitely make us poorer

The Leave.EU website said leaving the EU 'would mean money in your pocket'. It didn’t say anything about that money in your pocket being worth less.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1985 Nigel Lawson believed sterling was so weak against the dollar that a major market intervention by central banks around the world was justified.

The then Chancellor signed the “Plaza Accord” in September of that year in New York on behalf of the Thatcher government. That landmark deal was designed to bring down the value of the US currency against a host of other major currencies, including the pound.

Fast forward 31 years and sterling is back down to those feeble 1985 levels against the greenback thanks to the Brexit vote – a cause for which Lord Lawson was a leading champion. Yet times change. Lord Lawson, today, seems content with sterling’s low level.

Other prominent Brexiteers are equally relaxed. Some have suggested sterling was overvalued going into the 23 June referendum – and that what we are witnessing today is merely a natural correction. Yet this was not something they said before the vote.

The strikingly optimistic GDP forecast from the maverick Economists for Brexit group presumed the level of the trade weighted sterling index would be 89.8 in 2016, moderating only slightly to 88.2 in 2017. The current level? 76.5.

In fairness, Nigel Farage did countenance the possibility that sterling could fall “a few percentage points” after a Brexit vote. The decline is, in fact, more than 10 per cent against sterling and the euro and still dropping.

It’s worth reiterating the implications of sterling’s rapid depreciation. It means more expensive holidays for Britons heading abroad – as many travellers will have already discovered the hard way.

Down the line it is likely to push up inflation sharply as the price of imports rises. This will squeeze the purchasing power of people’s wages. The Leave.EU website said leaving the EU “would mean money in your pocket”. It didn’t say anything about that money in your pocket being worth less.

There are, granted, countervailing positive economic effects too. Sterling’s depreciation has already increased the price competitiveness of the exports of UK businesses – and this seems to have boosted manufacturing order books since June.

But there are negative impacts on importers too. The cost of the dollar-denominated raw materials that many UK factories and business need is rising fast. And these costs will be passed on to British consumers in the end.

It’s also worth remembering that the large depreciation of sterling in the global financial crisis of 2008 was much less of a stimulus to our domestic exports than we hoped.

The truth is that it’s difficult to say with any degree of certainty what the net impact of currency depreciations will be for an economy and the living standards of its population.

A more useful exercise is to consider why the currency markets are reacting in this way, sending sterling down to a new 31-year low this week.

Is it because currency traders are embittered Remain supporters, selling the currency out of pique? This doesn’t seem very plausible given their job is to make money by anticipating changes in the market price of the currency.

Could financiers be manifesting their narrow worries about the survival of the City of London’s “passport” to sell services into the rest of the EU in the wake of Brexit? Are they allowing personal fears about the dire prospect of having to leave funky London to work in boring Frankfurt skew their judgement? Again, that doesn’t seem very plausible given they are liable to lose money if they trade on emotion.

Granted, markets can get things wrong. And they can overshoot. And it’s true that many things move currency markets, from domestic interest rate expectations, to money printing by central banks, to divergences in monetary policy between different states, to even big foreign takeovers.

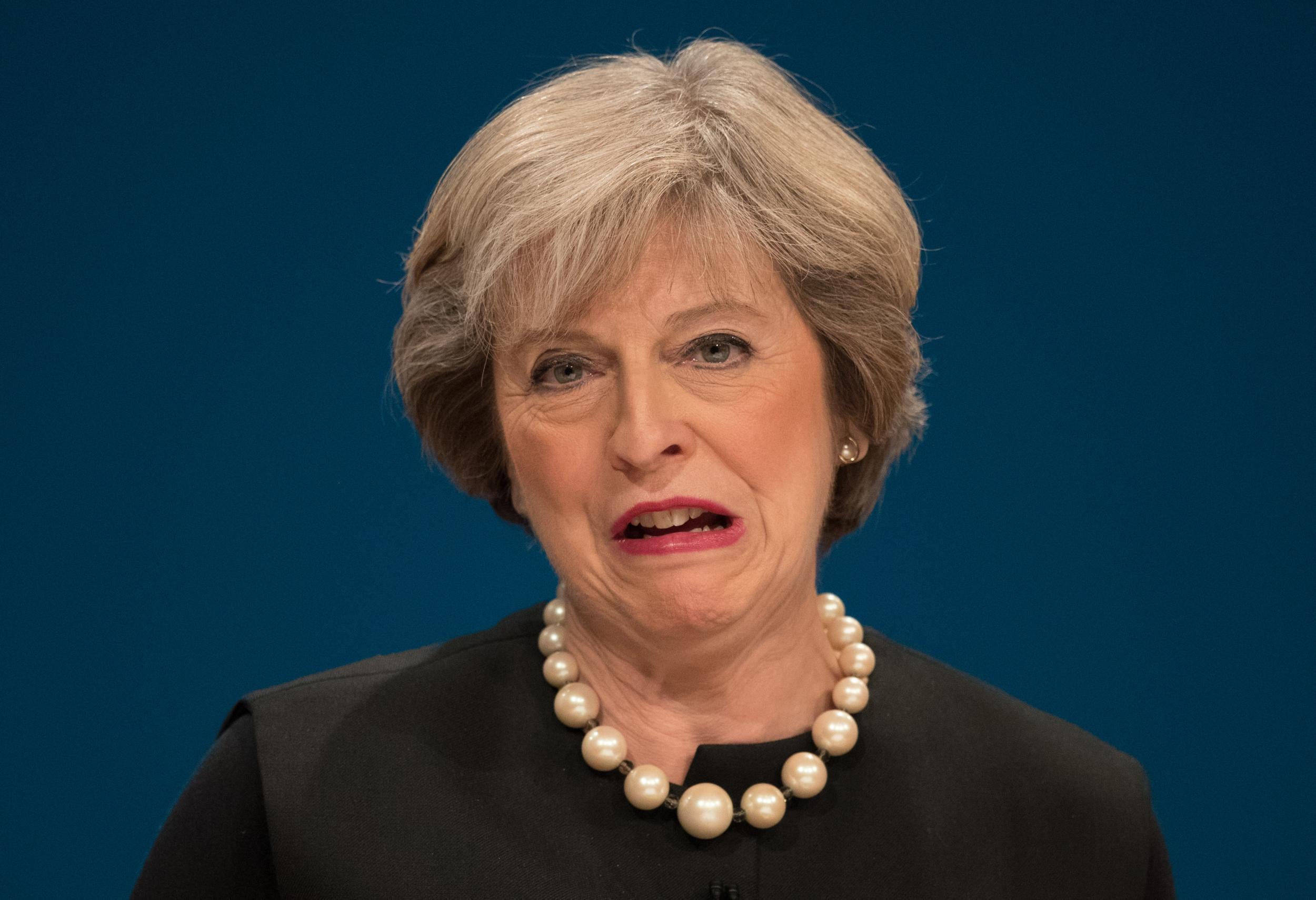

Yet there was only one big piece big news on 23 June when sterling haemorrhaged all that value: the Brexit vote. And this week’s renewed downward lurch has coincided with Theresa May saying she will trigger Article 50 before next March and making it clear that she will not compromise on curbing EU immigration to the UK, something that strongly implies Britain will be out of the single market by 2019.

The fundamental reason for sterling’s descent is that traders believe there will be lower demand for sterling assets as a result of Brexit – that we will ultimately do less trade with the rest of the world and that we will be poorer as a result. Argue the markets are wrong if you want to – but recognise what they are saying.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments