After Brexit, Britain is free – but it will never be a global power again

Washington is already moving its focus from London to Berlin. This is a dynamic we should expect to repeat itself in every international political relationship the UK has

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The UK’s vote to leave the EU has already had a number of worrying effects. The strength of the pound is in question, and the leadership of the Labour Party and Ukip are still in disarray. For those in the Remain camp, this was all utterly predictable; it is the canary in the coal mine. Those who sided with the Leave campaign, however, are more sanguine.

The current political and economic turmoil will subside, they say, and with time the UK will bounce back with an even stronger economy and greater political autonomy – just some of the many positive by-products of reasserting the national power that had been lost to the much-maligned bureaucrats in Brussels. The logic is simple: although the UK was already in command of its foreign and military policy, by cutting the institutional ties that bound it to Europe it will regain freedom of action over that other major element of great power status – the economy. It will become sovereign once more, and thus able to chart its own course.

But the idea that the UK will gain power by removing itself from the EU is based on a profoundly mistaken understanding of where the UK’s great power status comes from. While it is tempting to reduce state power to military capabilities and economic power, such a calculation fails to appreciate the other forms of power that states can accrue. But while harder to measure, less-tangible sources of power have been the foundation of the UK’s great power status for much of the last 70 years.

In recent years, the maintenance of these sources of power was strongly dependent on the UK being in the driving seat of a continental political entity. So severely will these foundations of power be eroded by Brexit that their loss will far outweigh any putative economic benefits the UK may achieve by leaving. To put it another way, even if the UK’s economy grew as a result of its decision to leave – an outcome few predict – Brexit would still mean the end of the UK as a major power.

It has long been acknowledged that the UK has been punching above its weight on the global stage, but people are less clear as to why this is. Since Anthony Eden’s failed attempt at asserting neocolonialist control over the Suez Canal in 1956, the UK has commanded a declining share of the world’s economy and a declining military budget, especially relative to other great powers. Yet, despite this material decline, it has retained an outsized influence on global affairs.

There are several reasons for this, such as the remnants of imperial relationships including a shared history and culture with the hegemonic US. But, we contend, a major reason has been due to its position as a key player, along with France and Germany, in the EU, a polity that could jostle with the US and China at the top of the global hierarchy. This position generated at least three different forms of political influence that it will now lose.

First, the most obvious benefit of being a senior partner in the EU was that the UK could help to navigate the shape of the European project in a way that met its particular foreign and economic policies. Leavers were certainly right that Britain sometimes had to take deals that did not suit it, but the reality was that the UK was able to set the terms of the EU’s institutional structure. The UK’s presence in the EU helped to steer the project towards being more market-friendly than it otherwise might have been.

UK membership also acted as a brake on the integrating tendencies of the EU, preventing the centralisation of too much power on the continent. Membership thus allowed Britain to help meet two of its longstanding strategic goals since the time of Napoleon: the promotion of European free-trade and the prevention of the emergence of a continental hegemon. Outside the EU, it can no longer meet these goals through institutional design and management. Instead, it must rely on its traditional power capabilities which, when arrayed against the market fortress that is the EU, will have far less impact.

Second, as a consequence of being the 'sceptical' member of the EU's leadership triumvirate, the UK also gained a number of followers inside Europe. Britain’s suspicion of Brussels’ authority and its preference for a more market-oriented union are shared by many other states in the EU, most notably the post-communist Eastern European members who acceded in the last 15 years. As the strongest representative of these shared interests, the UK could credibly act as spokesperson on their behalf. The ability to speak on behalf of many other states (either implicitly or explicitly) meant that the UK had to be listened to and courted by other states. Now that it is headed out of the EU, Britain cannot claim to represent a broader constituency of states.

Of which state is this post-EU UK representative, except itself? Eurosceptic states inside the EU will have to form a new bloc to meet their interests while Eurosceptic states outside the EU will bypass the UK entirely in having their concerns addressed.

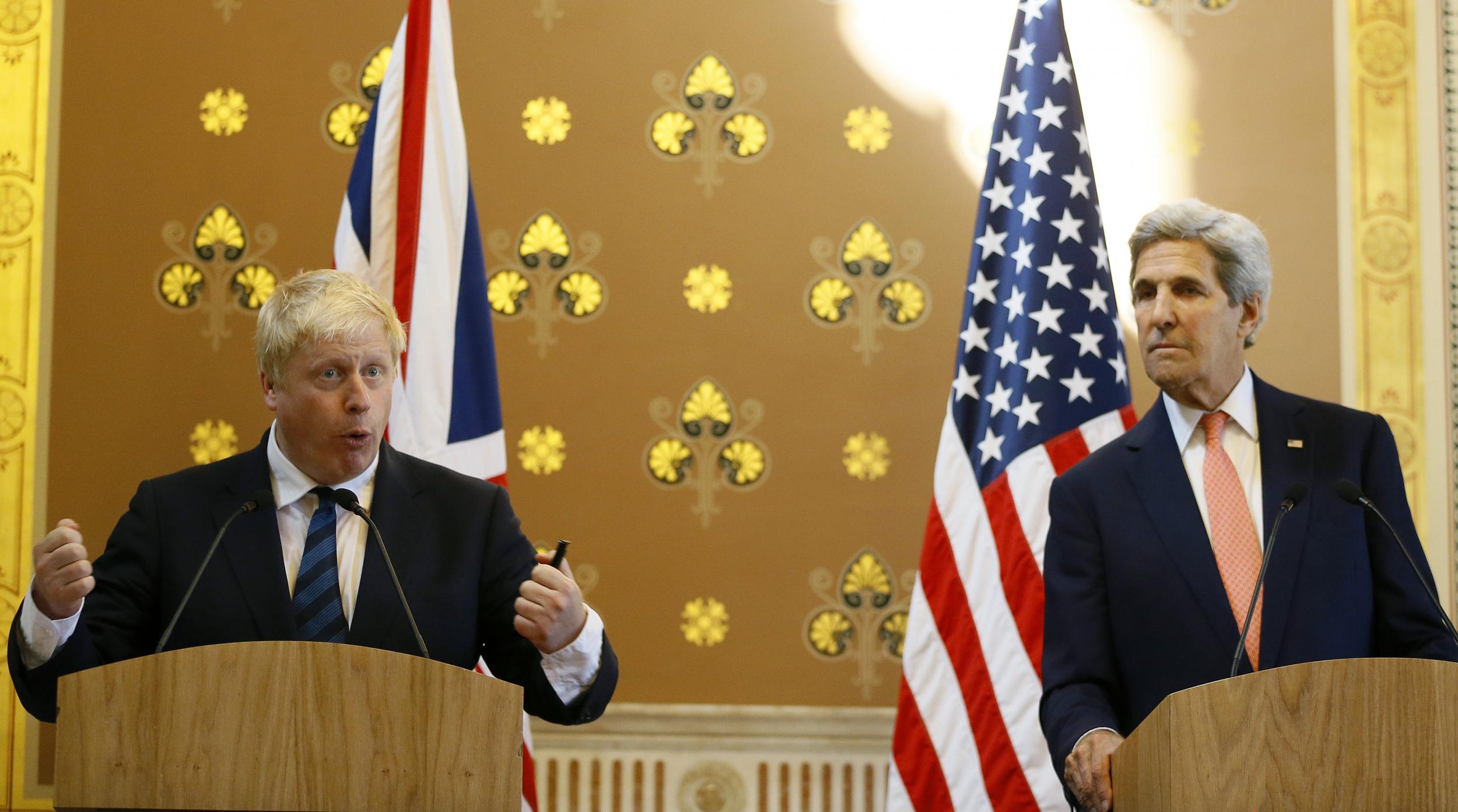

This last point illustrates the final element of British power that has been shattered by Brexit – its position on the global stage. The UK’s privileged position inside the EU meant that it was an important “plug socket” into the EU for outside states. Consider the much-vaunted "special relationship" between the US and the UK. The quid pro quo for this was reasonably clear: in return for American support of British interests, such as in Kosovo in 1999 and in Libya in 2011, the UK would act as an advocate for US ideas and policies inside Europe.

But this relationship was dependent on Britain’s access to, and positions within, the decision-making apparatus of the EU. With its new found “freedom”. the UK is a political outsider, with less political intelligence, fewer British personnel in key positions and less good-will with European officials. Thus it is less able to promote US interests in Europe.

Indeed, Washington is already moving its focus from London to Berlin. This is a dynamic we should expect to repeat itself in every international political relationship the UK has. Its important role as seasoned broker in the UN Security Council will be reduced (most likely in favour of France) when other diplomats realise that Britain will have a harder time bringing the other Europeans along. The same will be true in the G7, the G20, the WTO, the IMF, and of course, the EU itself.

Brexiteers claimed that by leaving the EU they would finally cut the ropes that tied the UK down and prevented it from achieving its potential. But they failed to realise that the UK had already far exceeded the political potential that its GDP and military capabilities suggested it deserved. Rather than binding its political power, the UK’s close ties to the EU helped it to have an outsized influence on the continental and global stage.

Now the ropes have been cut, in this – and far too late – those ropes have been found to be the UK’s political lifelines. For the first time since 1973, the UK will truly be on its own, forced to rely far more on its raw economic and military power than it has for a generation. This does not augur well. In the modern interconnected world naked power is an inefficient tool of statecraft and states more often meet their interests through subtler forms of influence.

Yes, Britain is free of one of the most complicated institutional structures in history. But political freedom can also mean political isolation. Just ask Russia.

David Banks is a professorial lecturer specialising in political history at the American University in Washington DC. Joseph O'Mahoney is a Stanton junior faculty fellow in the Security Studies Program at MIT and an assistant professor in the school of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments