Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

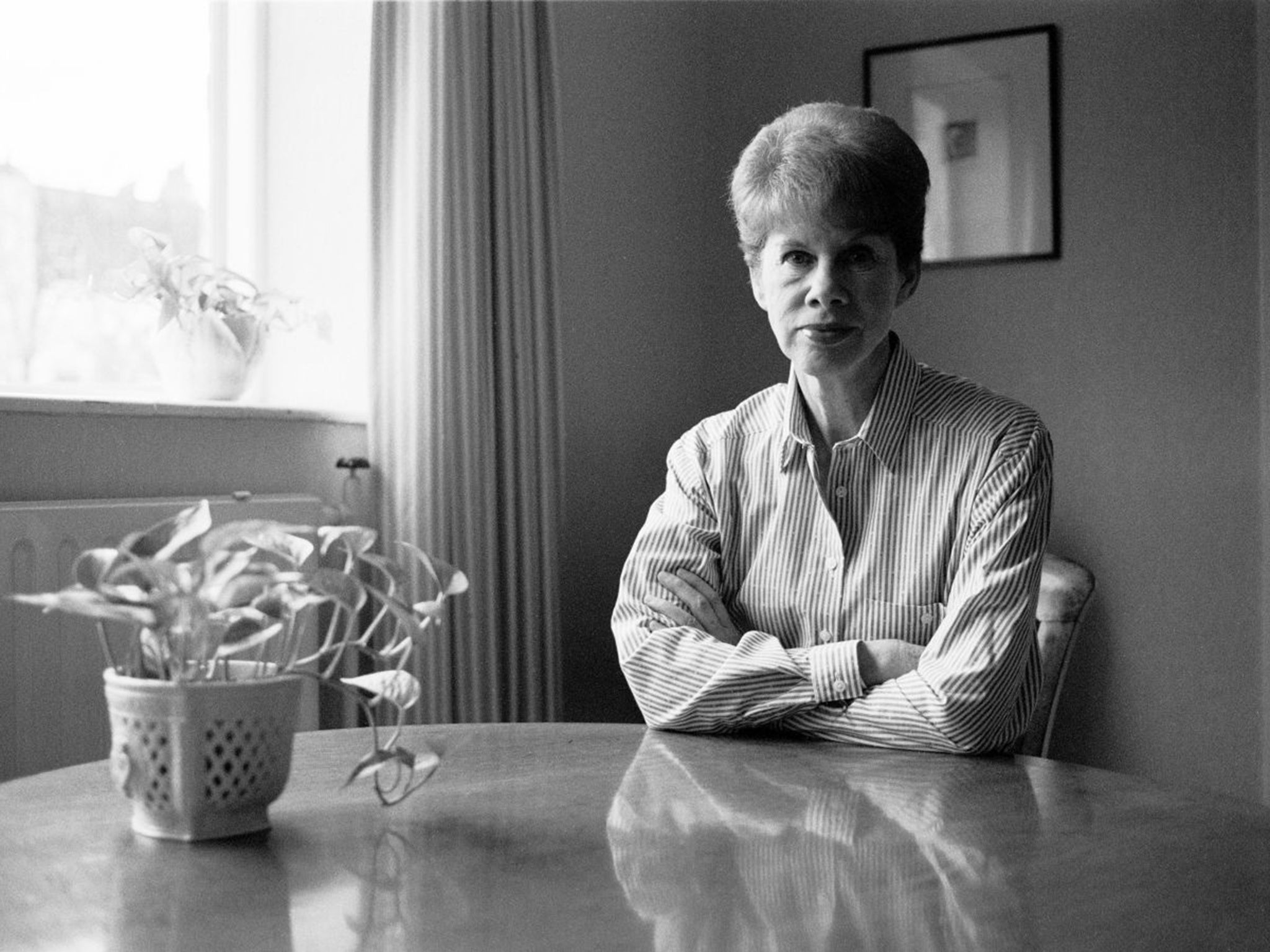

Your support makes all the difference.I only once set eyes on the distinguished novelist Anita Brookner, who died last week at the age of 87, at a party held some years ago at The Spectator’s offices in Old Queen Street. She said little, shook hands in a rather stricken way and left early, leaving the celebrations to continue without her.

As Dickens remarks of Cornelia Blimber, the bluestocking schoolmaster’s daughter in Dombey and Son, there was none of your light nonsense about Miss B. On the other hand, there is evidence that she possessed a slightly more worldly side. Her fellow writer Jonathan Coe remembered coming across her once in the fiction section of a west London library, he searching for copies of his novels under “C”, she looking for copies of her own under “B”.

If Miss B was not above checking out her availability on the bookshelves, then her many obituaries seemed to confirm a reputation for personal austerity and self-effacement. She began writing as late as her early fifties – an age when many novelists have a dozen or more books behind them – regarded what she produced as “displacement activity” and once commented that she wrote to stave off boredom.

The great advantage of putting words on paper, she confided to an interviewer from The Paris Review, was that it had “freed her from the despair of living”, to become , in the end, a way of “editing” a life that had begun, as she discreetly put it, “on the wrong footing”.

As far as one can make out, the roots of this dissatisfaction lay in the circumstances of her upbringing. The solitary child of Polish immigrants – the patronym was Bruckner – growing up in a household that constantly expanded to take in displaced Jewish relatives from Mitteleuropa, she swiftly came to the conclusion that “everybody was unhappy”. Her mother’s life had apparently been blighted by her decision to marry the wrong man. Her parents disapproved of their brilliant art historian daughter’s acceptance of a French government scholarship to study at the Ecole du Louvre in Paris and supposedly “cut her off”, although this did not stop her from taking time out from her job as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Cambridge to care for her mother in her final illness.

All this inevitably leached into the novels she began to write in the early 1980s in summer vacations from the Courtauld Institute, where she was appointed Reader in 1977. A Start in Life (1981), she said, was written “in a moment of sadness and desperation”, when her life seemed to be “drifting in predictable channels”. The success of the Booker-winning Hotel du Lac (1984) made little difference to a modest and unassuming manner of existence whose principal relaxation seems to have been walking the London streets.

Writing, she once confessed, was her “penance” and the isolation in which her books were conceived a terrible strain. She gave few interviews, declared that her ambition was “to be unnoticed” and declined all invitations to appear at literary festivals and radio programmes or take part in academic seminars in which the future of literature is discussed.

Brookner was clearly a rather unusual human being, but she was also a rather unusual artist. Naturally, there have always been great literary, cinematic and theatrical showmen and women – think of Dickens’s barnstorming lecture tours of the 1860s, or Oscar Wilde’s progress around late 19th-century America – but the majority of 20th-century English writers would have thought it “bad form”, to use that ancient phrase from the public-school playground, to go touting your wares and your personality around the country like a commercial traveller.

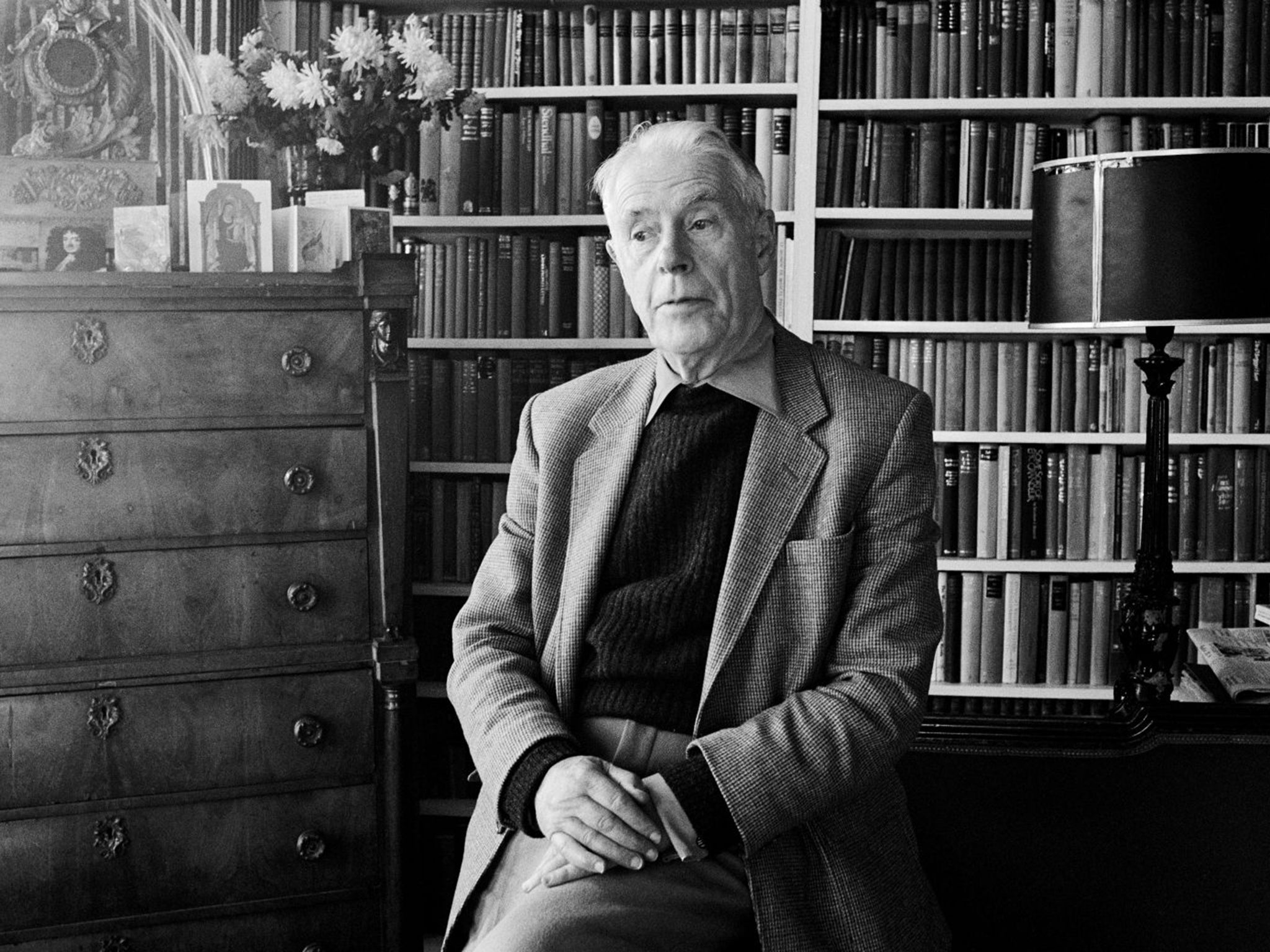

Anthony Powell, for example, would not sign a book for a person he had not met, and you can only imagine the reaction a publicity assistant from Evelyn Waugh’s publishers would have received in the early 1960s had he or she greeted the legendarily cantankerous author of Brideshead Revisited on the telephone with the words “Hi Evelyn, they’d love to have you at Cheltenham, and the people at Essex wondered if you’d like to take part in a sponsored bike ride for World Book Day with Graham Greene and Aldous Huxley”.

Half a century later the writer is essentially a performance artist, judged, in an age where a festival appearance is quite as important as a rave review, for his, or her, ability to sway a crowd, raise a laugh or fan the flames of a controversy. “We had X here last year,” festival organisers will grimly confide in town-hall green rooms as the Tannoy crackles overhead and the queue winds round the corridor to the signing tent, “and he was awful. Didn’t look up from the lectern, mumbled over his reading and wouldn’t answer a chap who asked if the woman in his new book was his ex-wife.” The fact that X, author of that Costa-winning slice of East Coast noir, Cleethorpes Confidential, might be terrified of appearing in public and pining for the solace of his hotel-room mini-bar, is irrelevant. To be able to sing for your supper is at least as important as the sparkle, or otherwise, of your prose.

None of this cut any ice with Miss Brookner, who, as far as we can make out, distrusted flamboyance as much as she (eventually) came to distrust her own talent. A prolific author, who produced a novel a year until she reached her eighties, she thought she should have stopped with Latecomers (1988) and judged that she had won the Booker with the wrong book. But what she also distrusted, as her obituaries made clear, was that widely held contemporary belief about the absolute importance of “having it all”. Close to marriage several times, but always ultimately evading it, she found herself caught in an unenviable Catch 22 – writing her books to free herself from despair, longing for “ideal company” but fearing that the demands of a relationship would have impinged on the work that acted as its substitute.

“I could get into the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s loneliest, most miserable woman,” she remarked in 1984. This may, or may not, have been meant as a joke, but in either case it was not something you could imagine any of her contemporaries owning up to. On the other hand, by sticking, however unhappily, to her guns, and pursuing an undeviating aesthetic line she produced a body of work that may well last longer than much of the stuff written by the modern performance artists. There is a moral here somewhere. Meanwhile, I calculate that this is the 375th column I have written for this newspaper in the past seven and a half years. It is also the last. My best wishes to readers past and present, and thanks to the editors who have indulged me for so long.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments