Philip Larkin's Hull: Marking 30 years since the poet’s death

Stuart Forster follows the Larkin Trail around the city and beyond

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

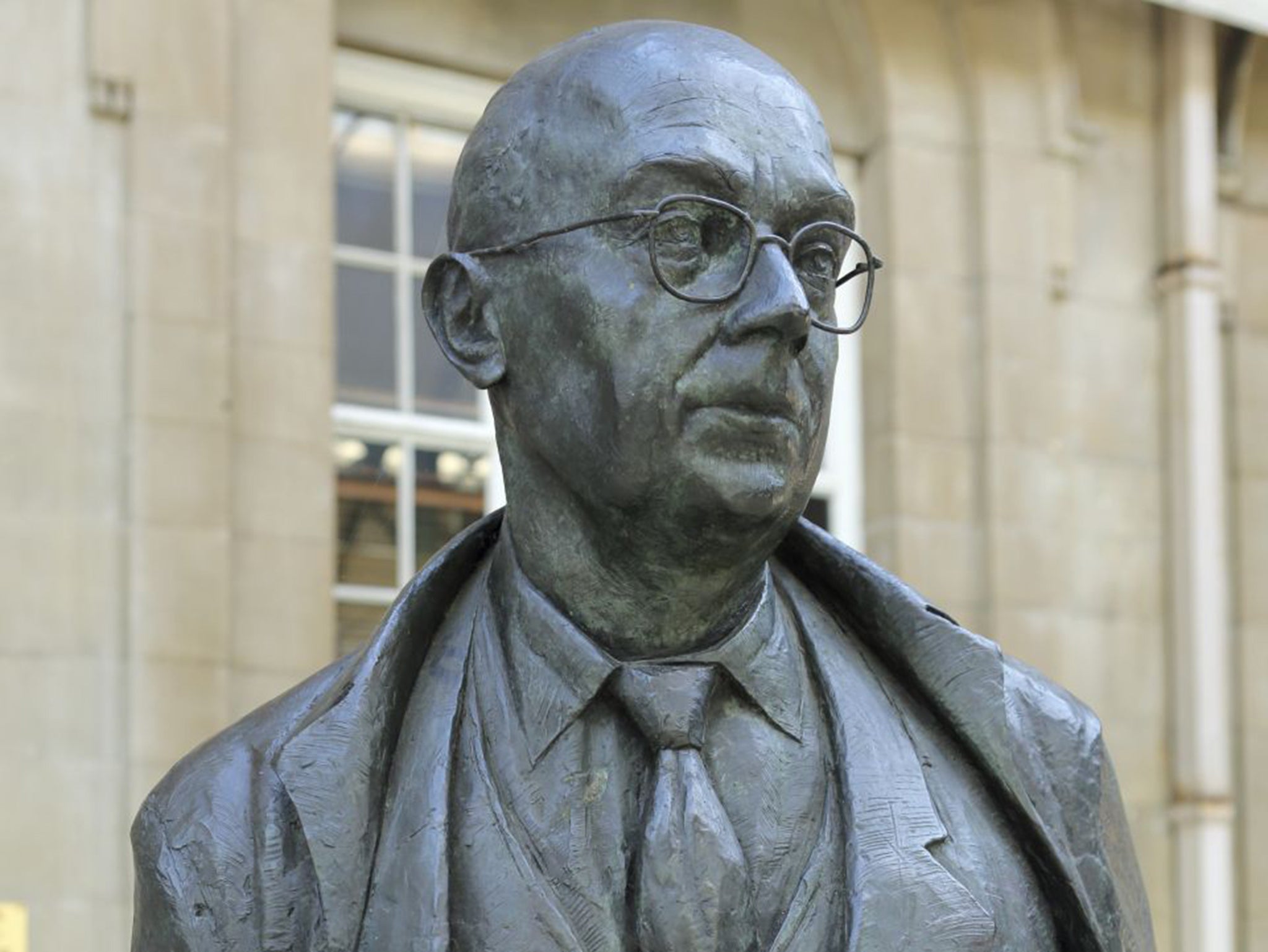

Your support makes all the difference.A lone figure stands on the white concourse at Hull’s Paragon railway station. Stern, bespectacled, and holding a book, the life-size statue depicts Philip Larkin, who lived and worked in Humberside from 1955 until his death in 1985.

The city will mark the 30th anniversary of Larkin’s death today, on what would have been the poet and university librarian’s 93rd birthday. A concert will be held at the Paragon this evening, with new musical compositions due to be played at further sites along the Larkin Trail.

The trail was established five years ago and extends beyond Hull to sites around East Yorkshire, including Beverley, Cottingham, and Spurn Point, on the Humber Estuary. It gives visitors “a feel for what life was like for Larkin in Hull and also the kind of things that influenced his writing,” explains Philip Pullen of the Larkin Society when we meet at the lobby bar of the Mercure Hull Royal Hotel.

Numbered signs mark the route, whose central section can be walked within a couple of hours. They bear geographic coordinates, quotes from the poet, and snippets of information relating to his life. The trail starts at the hotel, the setting of the poem “Friday Night in the Royal Station Hotel”, then heads into Hull Old Town via the City Hall and Maritime Museum, grand Victorian buildings on Queen Victoria Square.

The trail also provides an overview of Hull’s compact, historic core. Despite being one of Britain’s most heavily bombed cities during the Second World War, much survived, including the Holy Trinity Church. Locals claim it’s the country’s largest parish church. The building’s origins date back more than 700 years to the reign of King Edward I, the monarch after whom the municipality was named Kingston-upon-Hull.

It soon becomes apparent that Hull is by no means short of pubs. Larkin enjoyed a drink and the trail skirts by The White Hart and Ye Olde Black Boy. Resisting the temptation to have a pint, I continue past the pleasure boats docked in Hull Marina and on to the wooden boardwalk of Victoria Pier, from where paddle steamers used to cross the broad, shimmering Humber. Its confluence with the River Hull is just yards away. Thanks to the low tide and summer sunshine I see evidence of the “shining gull-marked mud” Larkin described in his poem, “Here”.

“It’s a great description of this area in the 1960s – very evocative of what Hull was like,” says city guide Paul Schofield of “Here”. We walk together from the Museums Quarter to the Queen’s Gardens, a public park on the site of a filled dock that was England’s largest when it opened in 1778. On the way we pass another of the Larkin Trail markers on Land of Green Ginger, the quirkily named street whose George Hotel bears a brass plaque by the slit-like opening of what it claims is England’s smallest window.

At Hull History Centre, an angular contemporary building containing around 12km of shelving, I meet senior archivist Simon Wilson. The archive holds more than 70 Larkin-related collections, including all but one of his workbooks, more than 1,000 of the jazz LPs he used to review, plus letters and items such as his shoes and spectacles.

Anyone can request to view items held in the archive. Larkin was a keen photographer, so I take a look at his cameras before leafing through albums holding his prints within plastic-sleeves. He made photographic studies of people, as well as taking numerous shots of cows in fields. “It adds a dimension to his poetry and the people and places he writes about. We have several shots of a hedgehog in his garden, before the unfortunate encounter with the lawnmower,” Simon jokes – a reference to Larkin’s poem, “The Mower”.

Another section of the trail goes beyond the city centre. It includes locations such as the Nuffield Hospital, where Larkin died on 2 December 1985, and Pearson Park, close to the house in which he lived and wrote “High Windows”. Heading to this part of town takes me towards the university and along Newland Avenue, a street with numerous independent shops and cafés, where Larkin spent time.

One of the trail’s key points is the University of Hull’s Brynmor Jones Library, where Larkin worked and oversaw major structural developments during the 1950s and 1970s. The building hosts a permanent exhibition of British art, dating from 1890 to 1940, including works by Wyndham Lewis and Henry Moore. During my visit, artist Rebecca Dennison is putting the final touches to a maritime-themed work inspired by Larkin’s poem, “The North Ship”. Her “canvas” is one of 31 giant toad figures being displayed in the Toads Revisited public art project, which had its official launch this week.

The event follows on from 2010’s Toads exhibition, which helped elevate public awareness of Larkin in Hull. The projects’ titles were inspired by two of his poems. A handful of the original toads remain on permanent display, including at sites outside the Hull History Centre and Streetlife Museum of Transport.

I make the final part of my journey by car, to view Larkin’s grave at Cottingham Municipal Cemetery. He was a complex, multi-faceted character, yet the austere headstone bears only his name, the years of his birth and death, and one word: “Writer”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments