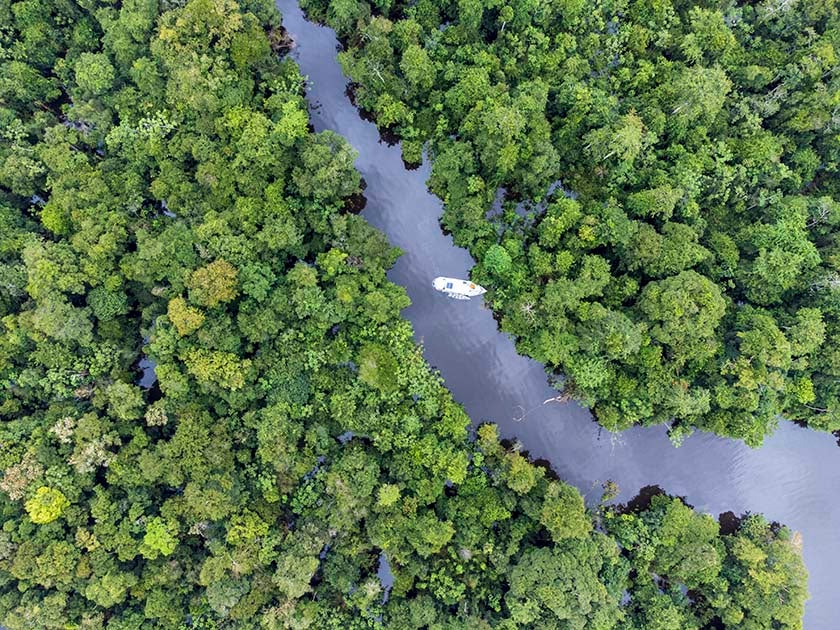

Brazil’s Rio Negro: Exploring the largest swathe of protected rainforest in South America

The Amazon is soul-quaking in all its forms, but to see true, pure, untouched rainforest with maximum wildlife – and minimum crowds – it has to be an eco-conscious tour to the Rio Negro, writes Alex Robinson

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Saro grabbed my arm and pointed into the flooded forest where the creek spread mirror-calm through endless trunks into darkness.

“Shhh!” he said, cutting the boat engine. We stopped talking and drifted slowly, like a fallen petal on the current. With the outboard silent, I noticed that the forest was alive with sound – the whirr of cicadas, the chic-chic of kingfishers, the chirrup of frogs. A pair of metre-long blue-and-yellow macaws flew over us, screeching raucously.

But I still couldn’t see what he was pointing at. I shielded my eyes from the sun and squinted into the gloom of the flooded forest. Handkerchief-sized, electric-blue morpho butterflies floated between the trees. A purple gallinule – like a giant, regal moorhen – waded over a bed of water hyacinth on spindly yellow legs. Then I saw a flicker; an undulation of something man-sized, swimming between the trunks. Then a sheen of wet, waxy fur flashed out of the water, illuminated in a shaft of light that pierced the canopy. There was a snort, followed by the sound of rapid breathing. Whatever it was, it was coming closer.

“Ariranha!” whispered Saro.

Now it was right by us. Something broke the creek’s surface a few metres in front of our prow: inquisitive, dark eyes; a sleek brow; and a face that came clear of the river, beady eyes staring right at us, with a dab of white under a big whiskered mouth filled with sharp teeth. I gasped.

“Ariranha!” repeated Saro softly, “A mother giant otter! She will call her cubs to come close. Watch!”

The mother let out a rasping cry, then three smaller faces bobbed behind her. They stared, inspected us from afar, as curious as cats, as cute as puppies – though each was as long as an adult labrador. Their mother cooed, played with her cubs and then suddenly remembered herself and barked sharply. An alarm warning. “Not food,” she seemed to call, “but danger!” Just as quickly as the family had appeared, they vanished, beneath the water and back into the trees.

I pinched myself. A giant otter in the wild! After decades of hunting, these spectacular animals have been pushed to the brink of extinction. To see one outside of a wildlife documentary was nothing short of extraordinary. To see a whole family filled me with hope. It was a sign not only that we were in the depths of the Amazon’s wilderness, but that, despite the ravages of Brazil’s Bolsonaro government, there are still large areas of the rainforest that remain well preserved.

There were a handful of us on the boat tour through the Rio Negro Environmental Protection Area – Brits drawn by a yearning for nature after a long stint in Covid-struck cities. But even pandemics have silver linings. I wouldn’t have found this astonishing Eden if it weren’t for those long, dull days searching the internet for dream journeys. On one I’d discovered Aracá Expeditions, a new boat tour company run by an indigenous Amazonian, Saro Munduruku. He promised to take visitors to the Amazon of his childhood, where wildlife was still thriving, water was still pure and landscapes magnificent. It was a crucial time, said Saro. Careful wildlife tourism was vital to keeping the rainforests he loved preserved.

Aracá is the only indigenous-run operator in the Amazon region. All the guides are local, with most being indigenous Amazonians. Money from my trip would go towards a reserve that Saro has purchased to reforest an area of degraded jungle around Novo Airão, and to collecting rubbish from the local waters. He strongly believes that tourism is essential to drawing attention to this pristine and beautiful area, and to showing that tourism can be a sustainable source of income for riverine people.

Saro, I soon discovered, was a local legend in Manaus, the capital city of Brazil’s Amazon, where most tours begin. Born into a family of fishermen in an Amerindian village in the 1960s, he had taught himself to read and write and to speak English and Spanish. He’d worked for 20 years as a guide in the many jungle lodges near the city, and as a fixer for wildlife documentary crews. But jungle lodges and short river cruises, Saro told me, sell visitors short.

“Tourists who fly in for a couple of days in a lodge or on a boat near the city have no more seen the Amazon than visitors to Miami have seen the Everglades,” he told me before my trip. “I take people to table-top mountains and giant waterfalls, clear-water rivers teeming with life, and floating forests where you can pick wild fruit right off the trees as you canoe.”

He was the one who suggested a river trip through the Rio Negro Environmental Protection Area, the largest, wildest protected swathe of rainforest in South America. We would visit the most remote mountain in the tropical world – the peak that gave Saro’s company its name: Aracá. Visits were important, he told me. They would help local politicians value and preserve the upper Rio Negro as an ecotourism draw, just as politicians in Costa Rica had learnt to protect its forested interior in the 1990s.

It sounded wonderful. But was it safe?

“The Rio Negro and Aracá mountain are as far away from the dangerous parts of the Amazon as London is from Cairo,” Saro told me. “There are no loggers, miners or cattle ranchers where we are going. And no mosquitoes.”

And he was right. I hadn’t felt so much as a nibble since we joined the boat in Novo Airão that balmy June, arriving when the rains were at their lowest and the rivers high enough to reach the mountain. This little port village sits 200km (124 miles) north of Manaus city, on the banks of the Rio Negro, the Amazon’s largest tributary. And not only were there no mosquitoes, the boat was luxurious: a beautiful river cruiser with air-conditioned cabins decked out in lush, polished wood and with a big, shady, hammock-slung observation deck. We had private showers, our own boat captain and a cook, Dona Zi, who welcomed us on board with icy caipirinhas. Soon we were puttering away from the jetty in warm, golden, late afternoon sunlight to cruise up the coffee-black Negro.

Even in Novo Airão, 1,500km from the sea, the river felt vast. What I thought was the opposite bank when we boarded was in fact a large forest-covered island – one of hundreds in the world’s biggest river archipelago, the Anavilhanas, a World Heritage site at the southern end of Earth’s largest area of protected tropical forest. As we headed west, the view of the Anavilhanas opened up: thousands of islands scattered the Negro, which stretched 30km wide. The scale and beauty of the landscape was overwhelming.

“Local people,” Saro told us, “don’t see the Amazon as a river – it is a vast, flowing, freshwater sea.”

Two fellow guests – Rob, a professional cartoonist from Battersea, and environmental scientist Raphael – were transfixed, staring at the vast dome of sky, where thousands of swifts and swallows flicked past on their way to their evening roost. For half an hour we watched in silence as the sun set golden, sending shimmers over the rippling water, silhouetting the trees on the islands. The mackerel sky above us pinked and tens of kilometres away, on the far horizon, lightning flickered under an anvil of cloud.

For two days we cruised through Anavilhanas, as the forest got wilder and wilder. We passed tiny villages with huts clustered around blue-and-white painted Catholic churches. Bubblegum-pink river dolphins played around our prow. Hawks as big as turkeys sat in the crowns of giant waterside trees. Our boat pulled a smaller launch, on which we took trips off the main river up spindly creeks and oxbow lakes covered in lilies, spying troops of gibbon-like black spider monkeys swinging in the branches, vast flocks of cackling parakeets and our family of giant otters.

On the third day, we left the Negro for the Danube-sized Demini on our way to Aracá mountain. Sat on the hammock deck under the stars, Saro shared some of its secrets with us. Aracá, he told us, is more ancient than the forest, older than life itself. An isolated, flat-topped tepui or meseta (plateau) that is over 1.5 billion years old, whose sheer walls rise right out of the forest.

The next day we stopped at the confluence of the Demini and the Aracá river, which flows right off the mountain. A tributary of a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, it was still twice as wide as the UK’s Thames river.

“Come!” said Junior, one of the boatmen. “We’re going to collect camu camu,” he said, throwing us a bucket. We sped away in the launch to a patch of floating trees. Coming closer, I saw that they were covered in dark berries as big and juicy as autumn grapes. In half an hour we had filled the bucket.

Back on the big boat, Dona Zi presented us with glasses of dark purple, tangy Camu Camu juice. “There is more vitamin C in this,” she told us “than in one of those fizzy tablets you buy in the pharmacy.”

The next morning, after a night of cruising, the Araca River looked half the size it had the day before. It was time to leave for the mountain. We moored in a natural harbour under giant trees, then headed upstream on the launch, cutting into a creek fringed with beautiful, pearl-white sandy beaches. There were birds everywhere: tanagers flitting across the water, more flocks of macaws, wading night herons and snow-white egrets. Saro pointed out a huge black-and-white king vulture drying its wings on a high branch. In places, trees had fallen across the creek, forcing us to pull the boat out over the beaches and back into the water. At last, coming round a bend in the river, we finally saw Aracá – a wall of rock capped with wispy cloud. It looked primordial in all the jungle, Jurassic.

“See that crack,” said Saro, pointing to a fissure in the face of the mountain, filled with scrubby forest. “We hike up there.”

We balked. It looked tough and steep, and I was no mountain climber. But Saro just laughed. “Don’t worry, it’s easy.” We tied the launch to the riverside, slipped on our packs and hiked for several sweaty hours along a path. Saro pointed out fresh jaguar footprints in the mud. We crossed a tiny stream on a wooden log bridge and stopped at a rushing clear-water stream for a cooling bathe in the mountain’s mineral waters.

We reached the base of the mountain and our camp for the night with aching muscles and fell asleep in hammocks to the lullaby of tree frogs and crickets. I slept lightly – nervous about the path up the mountain, scared of steep drop-offs and precarious ridges. But Saro was right: when we reached the trail after breakfast, it was surprisingly easy. We scrambled over moss-covered boulders and heaved ourselves up short sections using a rope – for psychological more than physical support. The forest around the path was splashed with colour from dozens of blue, pink and red orchids and bromeliads. A hummingbird whirred past, before I spotted a leaf-lounging beetle as bright as a club dancer caught in UV light.

After three hours we were on the top of Aracá itself. And we shared a view that only a handful of people see every year; a view that will never leave me, which filled me with energy and life after the long pandemic. It was as if we’d stepped back into a world as old as Eden. At our feet forest spread as far as we could see to every horizon – a green lawn of ancient life cut by sinuous rivers. There was no hint nor sound of humanity; not even a jet plane high in the sky. Only falcons soared over the trees far below us, and the air was thick with oxygen and the smell of streams. The sheer walls of Aracá stretched either side of the fissure we had climbed. And in the distance, a river flowed through forest, paused in a pool and fell wispy white into a canyon a quarter of a mile high.

Travel essentials

Getting there

British Airways offers direct flights from London to Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Manaus, your starting point for this tour, is a six-hour domestic flight northwest of Rio and a four-hour domestic flight northwest of São Paulo.

Rio Negro tours

Aracá Expeditions can arrange a 14-night cruise to Aracá mountain from £3,950pp, full board, including all transfers and two nights in Manaus, but not international flights.

Journey Latin America has an 11-night holiday to Brazil with a week-long lower Rio Negro cruise leaving from Manaus, plus time in Rio de Janeiro and Iguazú Falls, from £3,760pp B&B, including flights.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments