The return of the airship: Once the stuff of history, dirigibles are making a surprise comeback - from Nasa to Bedfordshire

Christopher Beanland looks at the rise, fall and possible rise again of the giant dirigible and asks if this comeback will fly

You would be forgiven for thinking that airships lived on only in steampunk fantasies or celluloid – in films such as Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade or The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. But like other forms of transportation technology that we assumed was moribund only to return from the dead like a horror-movie villain – trams, maglevs, double-decker buses, propeller planes – airships are back.

Only last month, Nasa floated plans for the so-called High Altitude Venus Operational Concept (Havoc). The project envisages a space station in the sky, hovering in the atmosphere above the planet Venus, re-supplied by airships that look like Zeppelins. Artists' impressions of the idea scream 1915 more than 2015, but perhaps dreamers such as Jules Verne and the real-life airship pioneers were just way ahead of their time?

At Cardington Airfield, on the outskirts of Bedford, the story has come full circle. It was here that Britain built the R101 airship nearly a century ago. The hangars are being repainted bright green and restored to their former glory. They are so vast that they are almost beyond comprehension – some of the biggest buildings in Britain, they could fit whole cathedrals inside them. The airships constructed here were initially wildly successful – they became symbols of modernism, like the hangars which held them, and began a process of rapid globalisation: the Empire State Building's mast was designed as an airship docking point in Midtown Manhattan. But the R101 crashed in France in 1930, killing 48, and, following the Hindenburg disaster seven years later, when the German airship caught fire and killed 36 people, airships were sidelined. Some returned in later years, mainly as "blimps" designed to hover above cricket or baseball stadiums and film the match.

But now airships are floating back into favour, trying again to conquer the world of cargo – and even passenger – transport. "Twenty-fifteen will be the year of the Airlander," says Stephen McGlennan, the chief executive of Hybrid Air Vehicles, a British company which is at the forefront of this new, yet old, technology. "We've been preparing and paving the way for a rapid-fire series of tests and developments in the next few months and we'll be flying later this year."

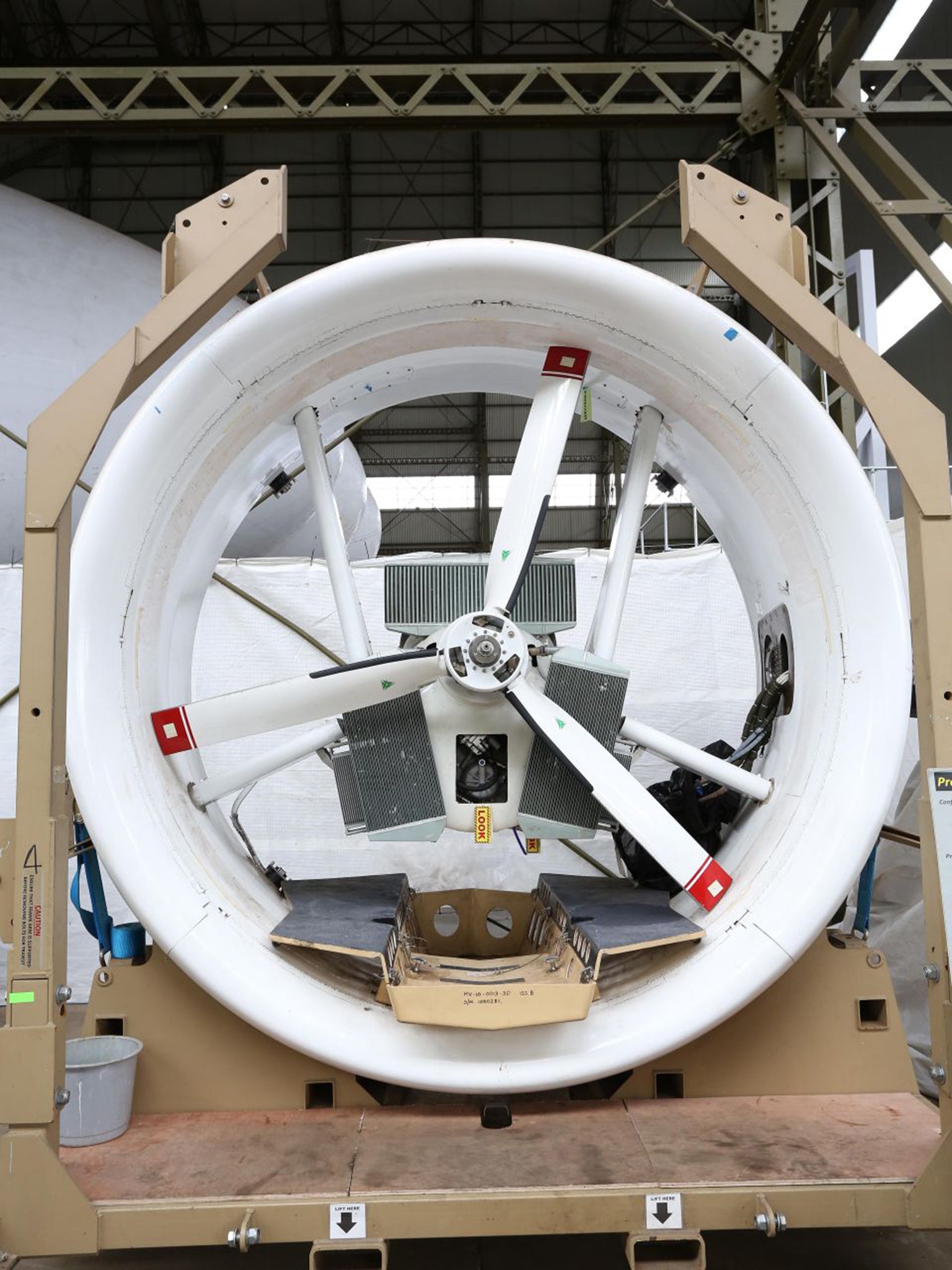

McGlennan hands me a hard hat and a fluorescent jacket and leads me out from the company's small office in one corner of the Cardington hangar, over to where the Airlander is parked. The wind whistles through the hangar; its size is truly monumental. But the Airlander itself is almost as impressive: a huge off-white balloon, its cabin and flaps sit on the floor next to it like a huge Airfix kit ready to be glued together. It looks lo-tech – and its relative simplicity is one of the selling points of the idea. It can operate in the wilderness or in cities; no runway is needed. Yet it takes brains to work out how to inflate it and how to make it fly – and carry 50 tons of cargo or 48 passengers.

"This month we'll be running engine testing on a purpose-built rig, and working with Cranfield University in detailed wind-tunnel tests," McGlennan says. "We'll also be getting our first helium supplies so that we can test our purification equipment. The Airlander is currently filled with air." McGlennan deliberately doesn't call this friendly giant an airship but, like all engineers, instead christens it with acronyms or abbreviations: it is a Hav (Hybrid Air Vehicle) which could also have a military use as an LEMV (Long Endurance Multi-intelligence Vehicle) – a surveillance platform that stays aloft for days. Later this year, the Airlander will be flying in the UK, if the Civil Aviation Authority approves the tests, and in Sweden, where it's being trialled to lift heavy bits of wind turbines over remote forests.

Airships hardly have an unblotted copybook, so I ask McGlennan if this one is safe. "The lifting gas used is inert helium – this is the least reactive element and therefore won't burn, explode or do anything much except ensure that fires or other types of reaction stop instantly." The opposite of the hydrogen used in airships of old.

"The hull has 12 separate compartments that can be isolated from each other. In tests, even when an old airship hull has been pierced by hundreds of bullets, the low pressure of helium inside, and the smart material used, means it's a few hours before enough helium is lost to cause it to start sinking. The Airlander has four engines and is designed to be flown on just one. It will float gently to the ground even if we had a simultaneous four-engine failure."

Could a trip to the Continent one day involve a routine flight on an airship rather than on a Boeing 737? Back in the office, McGlennan points to a huge world map and describes how flying by airship between close cities on the water such as London and Amsterdam, or between hugely congested metropolises near the sea – such as the cities of the Philippines – could make sense. Architects at Hawkins\Brown are big airship fans, and their drawings often invoke the floating beasts in the sky above proposed new buildings. The studio has mooted the idea for building Britain's first airship airport at Heathrow. But is it all hot air? "This could be a good idea," McGlennan says, "or it may be that we use a strip of water – one of the east London docks, perhaps, or even the Thames. Or an existing railway-station roof – we don't need a hugely strong structure to land on."

At first, though, the Airlander is likely to be pressed into service as more of a toy for luxury holidaymakers on safari. David Learmount, the operations and safety editor of the aviation-industry magazine Flight International, believes "the airship will for ever remain an aviation niche product". Hurdles will have to be cleared, but why not a new era of British-designed airships? If it's quiet, safe, cheap and doesn't require the expensive and ecologically damaging infrastructure of new airports, then tomorrow's airships might not be entirely pie in the sky.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments