Boutique hotels: 30 years of Schrager's blueprint

As Morgans, the self-proclaimed 'first boutique hotel', celebrates a milestone, Mark Jones charts the rise and rise of a hard-to-define accommodation concept

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.My room overlooked the swimming pool. It was early evening and a DJ was playing some thumping house music. The phone rang. It was Ian Schrager calling from New York. But in a way it was also Ian Schrager by the swimming pool. I was staying in Abu Dhabi's most monumental hotel, the Kempinski Emirates Palace. In 2014, it seems quite normal that a state-owned Arabic hotel run by a conservative German hotel chain should have a DJ playing house music by the pool, but it wasn't always thus. The idea of hotel-as-club, as curator of chill, jazz, dub and funk – that's a boutique hotel thing, and thus a Schrager thing.

The hotel he founded in New York 30 years ago, Morgans, also started the trend for hotels producing their own CD compilations. Some of Morgans' early ones by producer Ernie Lake are highly sought-after. So I apologised to Schrager if he couldn't hear me properly. "Mind," I said, "it is your fault".

"I take the credit," said the gravelly voice at the other end of the line. "And yeah, okay, I take the blame too. I guess it would have been unthinkable a place like that would have music by the pool."

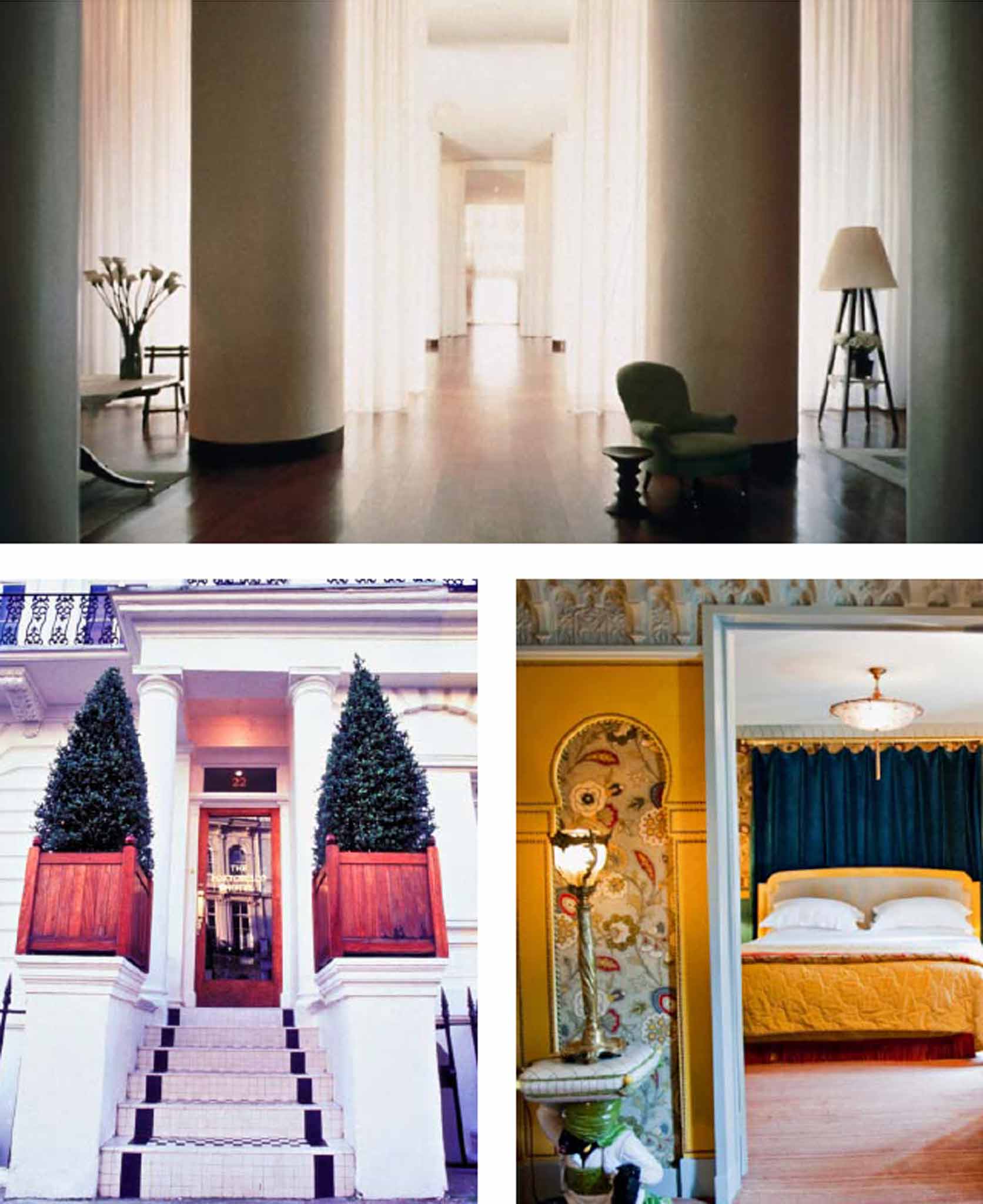

He can take the credit and blame for a few other things too. Attractive young hotel staff in suits that cost more than yours. Backlit bars. Foyer exhibitions. Antique chairs on cubist rugs. Front of house staff with curly earpieces. Noisy brasseries. Clashing fabrics. Haute luxe in small spaces. Mood lighting. And, of course, the re-invention of the word "boutique".

Schrager himself hates the idea that the boutique hotel can be reduced to a list of clichés. To him, every hotel should be different. But there is no doubt that Morgans launched an aesthetic that, three decades on, is stronger than ever. That's why an upmarket supplier of cocoa solids becomes Hotel du Chocolat and why they sell shaggy cushions and velvet throws in Tesco.

But who first used the phrase "boutique hotel"? Schrager describes the origin like this. In 1982-83 or thereabouts, his business partner, the late Steve Rubell, was trying to explain to the media what this new hotel was all about. The media were all over them. After all, these were the guys who launched Studio 54. You can't write an article or do a documentary about Seventies Manhattan excess and hedonism without mentioning that discotheque. It's on the statute books; a rather different kind of excess had landed them in the pen for tax evasion. These guys were hot; but hotels were kind of boring.

"So Steve says, 'Hotels are like department stores. They're trying to be all things to all people. This is different. It's like a boutique'."

And so it was that the pair appropriated a slightly dated term and launched a multimillion dollar category ... and a debate: what is boutique?

Schrager says: "It's a hotel that has a view. If you don't stick to an idea – don't have a specific attitude – that's the moment you become generic. A commodity. The only way of distinguishing yourself from the competition is by price."

A quick online search will tell you that lots of people – some formal lexicographers, some whose qualifications are a bit more open to question – are trying hard to define this thing. Three words recur, however: "small", "urban" and "individual".

Of these, Schrager entertains only the third. As long as you have the attitude and the individualism, he reckons, you can be a 1,000-room boutique hotel in the middle of the desert.

The question is, though, was Morgans really first? Actress-turned-designer Anouska Hempel opened Blakes in London in 1978, setting out to break just about every rule of hotel-keeping. "We didn't have any hard and fast rules. If you wanted to sit in the front steps or have a party in your room you could. If someone couldn't pay their bill we'd often ask another guest to pay it – or pay it ourselves. It attracted a certain kind of creative person," she says.

Small. Urban. Rock and Roll. A fashionable, bohemian crowd. For years, Blakes was in a category all of its own. "They didn't know where to put us," Hempel says. She no longer owns the place and I got the impression, though she was too polite to say so, that she thinks it's not the maverick, joyous thing it used to be. Boutiques are big business, and though Hempel herself never used the word to describe it, the hotel she founded now markets itself as "the world's first luxury boutique hotel". Her thoughts on the term? "It's been overdone. We need a new name."

The concept, however, could be traced even further back than Blakes. London has long had what could in today's terms be described as boutique hotels; in 1812, as Europe opened up for travellers and the very word "hotel" began to come into vogue in London, a small place called Mivart's opened in Brook Street. It was later taken over by a Mr and Mrs Claridge. The hotel bearing their name is still around, still in Brook Street, but is now by no stretch of the imagination a "boutique".

And seven years before Hempel's hotel launched, in 1971, a small place called the Portobello Hotel opened in Notting Hill. It was a landmark for a once distressed area of west London, and a small, largely unobserved sign that the innovative small British hoteliers, who had led the way in the 19th century, had got their mojo back.

Schrager knew about the Portobello. He also knows his hotel provenance. "London has a history of townhouse hotels," he says. "11 Cadogan Gardens was an inspiration too." He also namechecks L'Hôtel in Paris, the small temple of decadence (then L'hôtel d'Alsace) where Oscar Wilde checked out with two final bons mots: "I am dying beyond my means" and "Either that wallpaper goes or I do".

Interestingly, L'Hôtel is now part of The Curious Group, which also owns the Portobello and Cowley Manor, itself at the forefront of the rural-boutique trend that transformed Britain's weekending scene in the 1990s.

Today, the most high-profile players in the global boutique space are W, Andaz and Hotel Indigo. They are owned, respectively, by Starwood (owners of Sheraton), Hyatt and IHG (InterContinental Hotels Group).

In 2001, with Morgans already well established and Schrager blazing a trail with other properties such as New York's Gramercy Tavern, London's Sanderson and Miami's Delano, he told an interviewer it was "all over" for the mainstream hotel brands. Morgans, he said at the time, was conceived as "the anti-Marriott".

He denies that the exclusive, hip air of the new boutiques was an extension of the roped-off, no suits/no bores ways of Studio 54. "We're in business!" he says. "We can't afford to exclude people." But then he tells a story that seems to imply the opposite. A Midwestern couple at Morgans were struggling to find the lift button in the hotel's mood lighting. "The guy says, 'this is the hotel from hell'." The Schrager of those days was delighted his hotels were the Midwestern version of hell.

His latest enterprise is more "refined gritty" and "tough luxe", according to a recent press statement. 215 Chrystie, a collaboration with architects Herzog & de Meuron, is due to open in Manhattan in 2016 – a 370-room hotel topped with 11 one-of-a-kind residential units. So far, so Schrager.

In the accommodation business, though, you end up making accommodations. His next project to open is a hotel in Miami, which launches in November. It's the most recent in the Edition collection, following on from the success of the London Edition, which opened in 2013. Only it's not Schrager's hotel – Edition is owned by Marriott.

"They said 'we've forgiven you' – we laughed at it," says Schrager. "It's like the girl you didn't like when you were a kid and suddenly you find yourself wanting to marry her."

Five stars: Heroes of the boutique concept

Andre Balazs

Hungarian-born Andre Balazs is the brains behind Standard Hotels, which include the flagship Standard High Line in New York's Meatpacking District. Also in his portfolio are the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood: a venue so popular with the rich and famous that visitors are banned from taking photos inside. Following in the Chateau's exclusive footsteps is Balasz's latest venture, the Chiltern Street Firehouse, which has fast become London's celebrity hotspot du jour.

Wade Weigel

The first Ace Hotel opened in 1999 after Wade Weigel and the late Alex Calderwood bought a halfway house in Seattle and transformed it into an affordable hotel with luxury suites alongside budget bedrooms. Calderwood said at the time: "In a deck of cards the ace is both high and low." Ace Hotels have since set up camp in Portland, New York, LA, Palm Springs and, most recently, Shoreditch.

Priya Paul

Thrust into the business at a young age, Priya Paul took over the India-based Park Hotels aged just 23. Since then the chain, whose locations include New Delhi and Kolkata, has undergone a major reinvention with hotel bars and restaurants becoming more youth-focused, hosting music and fashion events. New properties are on the way in Pune, Kochi and Jaipur.

Rattan Chadha

Having moved into hospitality from fashion (he founded the Mexx clothing company), Rattan Chadha launched his first CitizenM hotel in Amsterdam in 2008, and has since added locations in London, New York, Paris, Glasgow and Rotterdam. The concept is high-tech and low-budget, cutting down on arguably unnecessary services (there's no restaurant, no concierge, no reception – check-in is DIY), but with modern essentials such as free Wi-Fi and blackout shades.

Robin Hutson

Starting out as a waiter at Claridge's, Robin Hutson went on to found the Hotel du Vin chain in 1994, turning a Georgian building in Winchester into a 24-room hotel. He has since chaired the Soho House Group, opened the luxury Lime Wood Hotel in the New Forest, and set up the Pig mini-chain in the South West.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments