Greek cuisine and Nikolaos Tselementes: Visit the birthplace of the nation’s Mrs Beeton on Sifnos

Every Greek kitchen has its Tselementes, a Cooking Guide full of tips and advice as well as signature recipes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

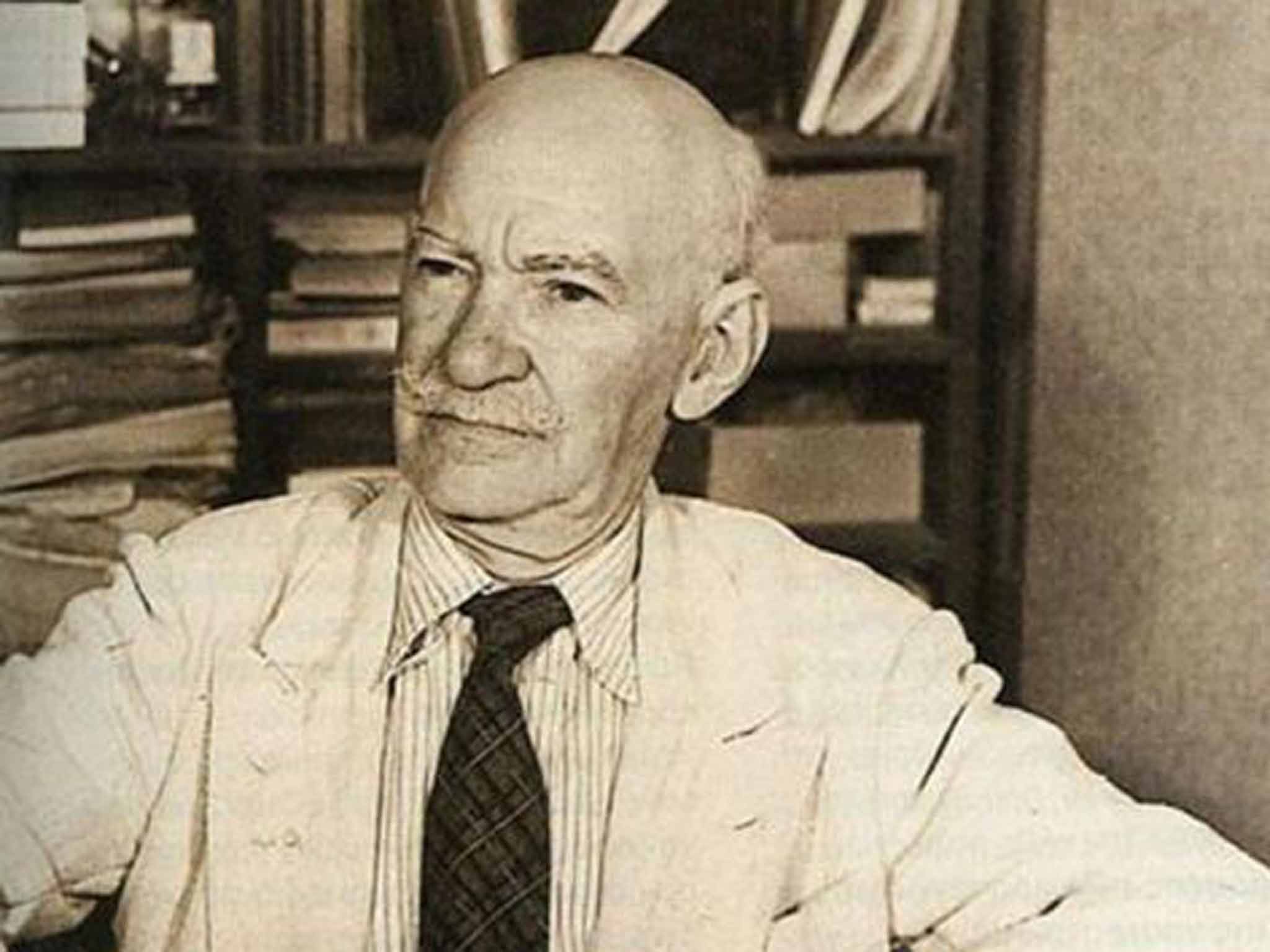

Your support makes all the difference.In a pretty little Cycladic village of whitewashed houses, along a narrow crazy-paved alley behind a blue-domed church, is the birthplace of Greek cooking as we know it. This traditional home, its light-grey door flanked by huge palm trees, was the home of Nikolaos Tselementes, whose name is in Greek synonymous with “cookbook”.

Tselementes started life here on the island of Sifnos, little known in the UK but a popular summer retreat for discerning Greeks. The island is regarded as a cut above, an attitude that may have begun as far as the sixth century BC when gold and silver mines made this one of the richest places in the ancient world – rich enough to build the ground-breaking (and partly surviving) carved marble Sifnian Treasury at Delphi. Visitors also come, of course, for the food linked to Greece’s most celebrated chef.

Tselementes moved from Sifnos to Athens before working in France, Italy and the US, but he often returned to his island home and is still remembered by the oldest of the island’s 2,600 residents as the man who cooked for them when they were hungry children during the Second World War. By this time he was already famous, having published the first Greek cookbook in 1910 (until then cooking had been an oral tradition) and his signature work in 1920.

Just as no English kitchen used to be complete without a Mrs Beeton, so – to this day – every Greek kitchen has its Tselementes. Like Beeton, his Cooking Guide is full of tips and advice as well as his signature recipes which combine traditional Greek cooking with elements from elsewhere in Europe, particularly France. It was Tselementes who brought béchamel to Greece, adding it to, among other things, moussaka.

“Is your cooking still influenced by Tselementes?” I ask the imaginative young chef-owner of Drimoni, an attractive modern Greek restaurant perched above the island’s tiny capital Apollonia. He answers by producing his own copy of the Cooking Guide and saying, as if I should not have needed to ask, “Yes. He was the best.”

Some of today’s Greek chefs think Tselementes’ variations on traditional dishes were vandalism; No Sifnian would be so rude about their most famous son but locals are at pains to point out that Tselementes did not create Sifnian cooking; it created him. Sifnos has a culinary tradition dating back into the mists of time – and Sifnos time goes back a very long way.

Centuries, even millennia-old, paths criss-cross this hilly island, offering commanding views as well as an insight into the island’s natural larder. The aroma of herbs – thyme, marjoram, sage – wafts up as I brush past. Caper bushes erupt from dry stone walls and olive trees drop their black gems on to the path. Mountain goats appear and disappear over impossible ridges. They provide milk for the local cheeses (soft mizithra, and hard manoura preserved in wine) and meat for traditional mastelo.

At Sifnos Farm, in the stone dining room hand-built last winter by farmer and cook George Narlis, we watch as he throws lamb, his own red wine and a fistful of dill he has just picked into a large, unfired red clay dish, a mastelo, before putting it in the oven to cook long and slow. He does the Blue Peter trick, producing one he made earlier, and I enjoy delicious tender lamb that falls from the bone, packed with flavour.

We eat his chickpea soup too; a hearty mix flavoured with olive oil, onion and bay that is Sifnos’s Sunday special. Put in the wood oven on Saturday night it is ready to eat after mass on Sunday. The chickpeas come from George’s “dry” farm. While most agriculture in Sifnos is irrigated, half of George’s smallholding has been returned to methods Tselementes would recognise. Using ancient local seed-types that require little water, George produces fruit and vegetables that are smaller than “wet” produce but more environmentally friendly and “10 times as tasty”.

Sifnian flavour, locals tell me, also comes from the clay pots they cook in, pots that have been produced here “since before Christ”. There used to be over 90 potteries on this 74sq km island; today there are 18 and clay continues to be extracted from the ground some 600m inland of the main tourist beach at Platis Gialos. Here, in his grandfather’s workshop, I find Frantzeskos Lemonis at his wheel. A potter since the age of 11, he conjures clods of clay into large elegant jugs and solid cooking pots.

Piled up next to his kiln, he points out the squat-lidded chickpea pot, the bowl-like mastelo, and the white straight-sided giouvetsi used for almost everything else. He makes little clay stoves too, and the typical vase-like chimneys that decorate rooftops across the island.

Many of these are now ornamental, but by no means all. In Artemonas – Sifnos’s second town – I find the elderly Mrs Theodorou bent over her stone hearths. In her immaculate little house-shop, she cooks traditional sweets: sesame pasteli, almond and honey amigdalota and halvathopita, a subtle nut-nougat between two wafers.

I am munching some of these delicacies on my last morning with a pot of Sifnian mountain tea (made from a kind of sage), enjoying a last look over Sifnos’s pretty capital and its monastery-topped mountains, when the phone rings. The wind is too strong, I am told; there will be no ferry today. This being winter, no-one is phased and I am immediately invited to supper by a sympathetic couple.

Here, I am treated to authentic Sifnian home-cooking: caper salad, rocket with pomegranate, island cheeses and pastitsio, pasta with mince meat and béchamel sauce. Sitting open on the middle of the table next to grandfather’s sweet raisin wine, is – naturally – Tselementes’ book.

Getting there

Ferries from Piraeus (Athens) to Sifnos take around three hours (€50/£40pp, cheaper on slower boats). It can also be accessed by ferry from Santorini in around the same time.

Touring there

Juliet Rix hired a car from Proto Moto Car (00 30 22840 31793; protomotocar.gr) which offers cars from €20 (£16) per day.

Staying there

Inn Athens (00 30 69471 29810; innathens.com). Doubles from €90 (£71) including breakfast.

Petali Village Hotel, Sifnos (00 30 22840 33024; hotelpetali.com). Doubles from €90 including breakfast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments