Edith Piaf's Paris: In search of La Vie en Rose

The singer died 50 years ago this week. Jonathan Lorie pays homage in the place of her birth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a cellar theatre in an alley in Paris, the singer steps up to the microphone and steadies herself. She's wearing a short black dress and very high heels. "Let me take you to a place not far from here, to Ménilmontant," she whispers, "let me tell you the story." As the piano rolls a thunderous refrain, she clasps her hands in prayer and hurls out a song that captures all the longing and loss of a desperate life.

"Mon Dieu," she roars at the bare ceiling, "leave him with me a little longer – one day, two days – to fill my life a little, to begin or to end, to brighten or to suffer …." With the piano pounding behind her, she belts out the final plea of a broken woman – "Even if I'm wrong, leave him with me a little longer" – and steps out of the spotlight, exhausted.

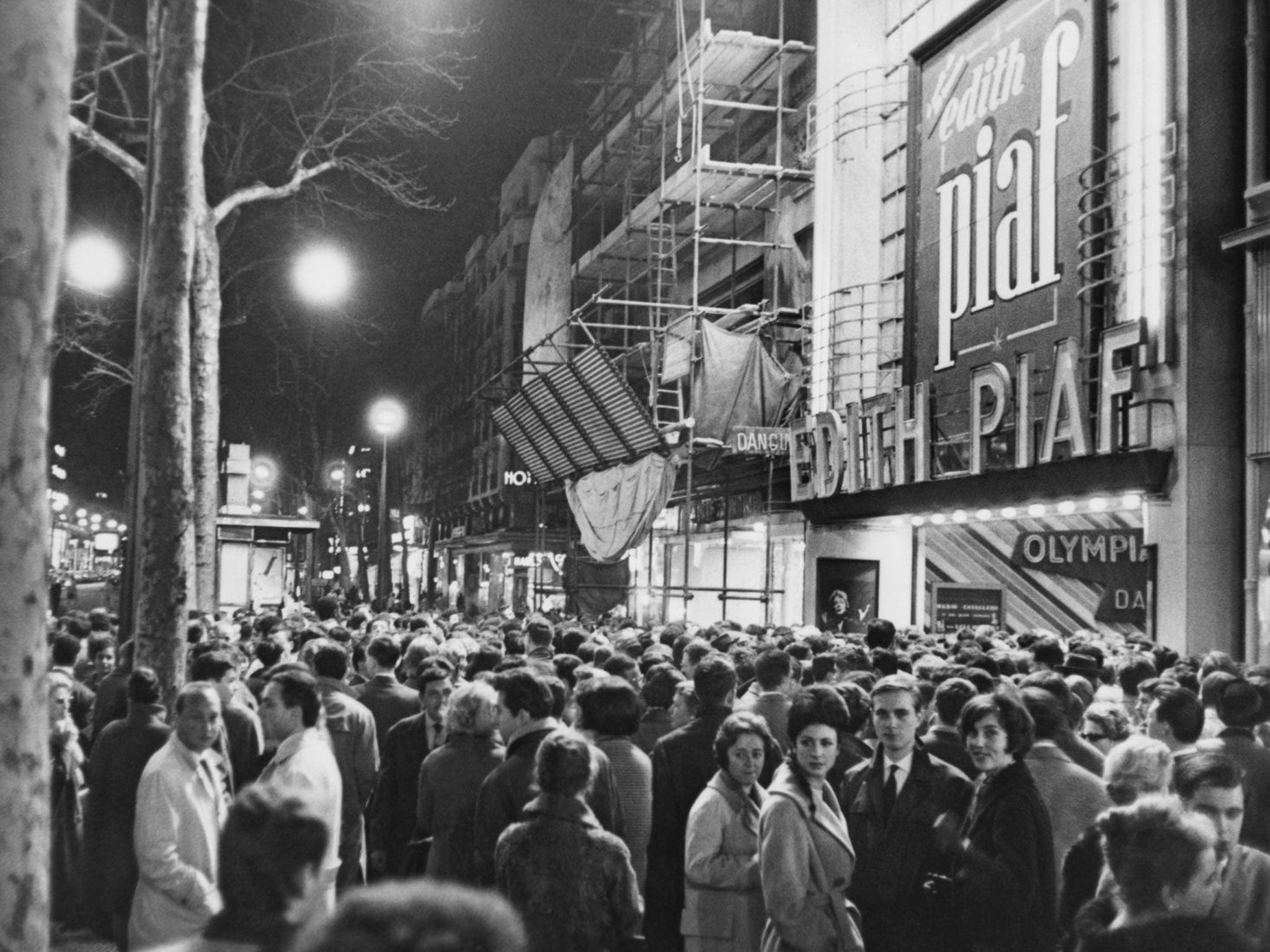

Fifty years ago, on 11 October 1963, the original singer of that song, Edith Piaf, died. She was the most popular – and perhaps the greatest – singer France has ever known. Her funeral procession in 1963 was attended by more than 100,000 people and stopped the traffic across Paris. Tonight her songs and her story are being revived by the jazz singer Caroline Nin, in the kind of dim-lit boîte where Piaf might have sung. Every song is an anthem of heartbreak and hope, of an era and a spirit in this city. And I've come here to discover Piaf's life and her Paris.

I step into her world next morning at La Coupole, the great Art Deco brasserie where Piaf sang in 1934, aged just 19. It's a glittering palace of the period with walls lined by mirrors and photos of the musicians and artists who made its great. Here Kiki de Montparnasse bathed naked in the central basin, Josephine Baker brought a cheetah to the table, and Giacometti sketched on the tablecloths.

These days it's a more restrained affair, where waiters carry trays of lobster and langoustine on crushed ice. I order lunch, an elegant sequence of champagne, poached salmon and peach salad – classic French cuisine, delicately done. Wondering where Piaf actually performed, I head downstairs and find a 1920s ballroom, complete with pillars carved like palm trees and a bar long enough to keep any party going.

But her life wasn't always glamorous. She was born in 1915, so legend says, in a doorway in Belleville, a rough part of town where her father was a busking acrobat. Her mother was a café singer of Berber origins who left when she was two. She was brought up by her grandparents, who ran a brothel. There she caught an eye disease that nearly blinded her. At the age of seven she was singing in the streets in her father's act – and earning more than him. The power and pathos of her voice always drew a crowd.

By her teens she was singing at the sleazy cabarets of Montmartre and Pigalle – such places as the Moulin Rouge, whose libertine atmosphere had been caught 20 years before by Toulouse Lautrec. She lived with a pimp, who tried to shoot her when she left him: the bullet grazed her neck. The pain in her songs starts somewhere in all this.

There's a choice of ways to get a sense of such things today. One of the nicest is to stay at l'Hotel, a boutique hotel on the Left Bank that was actually a brothel around the time when Piaf was born. Today, it's one of the finest hotels in Paris, with a Michelin-starred restaurant, but its Belle Epoque style is straight out of Lautrec – plum velvet drapes and gilded chandeliers, green silk wallpaper, and deep chaises longues. The music in the bar is Piaf.

In the brothel days, Oscar Wilde stayed here – and died in room 16. His still unpaid bill is framed on the wall, but the wallpaper he detested has been changed. Further along is the Mistinguett Room, dedicated to the cabaret singer whose legs were insured for 500,000 francs in 1919. It's a shrine to Art Deco, with her mirrored bedhead and dressing table, and lively posters of her shows at the Café de Paris and the Lido. In one she perches on a stool, wearing little beyond a string of pearls.

Intrigued by this, I head out in the evening to the Lido, one of the great cabarets of Paris. It seems a bolder way to enter Piaf's world. I don't quite know the form in such a place, but they seat me at a private table above the stage and produce an ice bucket of champagne, and I don't ask too many questions. There are 1930s lamps and a red beaded curtain across the stage. And then the show begins.

A giant egg festooned in purple feathers descends through the air and pops open to reveal a singer. Hordes of women dance synchronised numbers in fabulous costumes that seem to stop just below the bust. An acrobat does impossible twists on a length of white cotton dangling from the ceiling. The main temple of Angkor Wat rises through the stage and its stone dancers come to life. A mechanical elephant rolls into view. At the finale, those strings of pearls make their strategic appearance, and then the entire cast turns towards a screen at the back, where a film shows Edith Piaf singing "Hymne à l'amour".

I stumble out at 1 am, into the dark of the Champs-Elysées. Car lights spin around the Arc de Triomphe. I circle it to Avenue Mac-Mahon and turn off. At a junction with Rue Troyon, there's a triangle of pavement. Here Piaf was busking in October 1935, when a well-dressed man emerged from the crowd and gave her his card. You'll ruin your voice if you sing like this, he said, and asked her to audition at his nightclub. It was the break that changed her life. Louis Leplée took her on, trained her up, and gave her a nickname – Piaf, or sparrow, because she looked so frail. She was just 20.

Near here, too, in a café on the Champs-Elysées 10 years later, she wrote on a tablecloth the song that became her signature tune: "La Vie en Rose". Countless stars and films have used it since, but it was her vision of the highs and lows of life, from the gutter to the glitter, that make it soar.

Next morning, later than planned, I walk the streets of Belleville and Ménilmontant, looking for Piaf landmarks. It's still a run-down area, with a market selling second-hand goods off Rue des Pyrénées. I order coffee at the bar Aux Follies, where she sang before her break. It is wonderfully intact. Swirling neon lights announce its name across the white ceiling and walls, a cubist mosaic decorates the floor, and little iron pillars are plastered with ancient playbills.

Further uphill is a plaque marking the doorway where she was said to have been born – though more likely this was in the local hospital. In a backstreet nearby is the Musée Edith Piaf, in a two-roomed flat where she once lived. The displays include her black dress and the boxing gloves of her great love, Marcel Cerdan, who died in a plane crash in 1949. His death triggered a decade of alcoholism and drug addiction that wrecked her health. On the night after he died, she insisted on going onstage and singing "Hymne à l'amour", an ecstatic song she had written for him: she collapsed as she reached the chorus. Beyond here is the cemetery of Père Lachaise, where fans still lay flowers on her black granite grave.

For one last glimpse into Piaf's world, I go that night to the oldest cabaret in Paris, Au Lapin Agile. This tiny one-room club perches on a cobbled street in Montmartre, and has hosted singers since 1860. The Impressionists drank and danced here, and little has changed in the dark wooden room with its clutter of benches and paintings.

"Yes, Piaf sang here before she was famous," says Yves Mathieu, the 85-year-old owner. "She lived in the next street." His blue eyes go misty. "I met her. She was very natural, very open, and she did a lot to help others. People loved her because she was very French, very Paris, very street."

There's a hush in the club and a young woman steps into the spotlight. Malaurie Duffaud has dark hair and big eyes, a splash of red lipstick and a little black dress. She raises a finger and launches into a chanson of romantic defiance, "Je M'en Fous Pas Mal" (I Don't Give A Damn). It's a classic Piaf number, ending with anguish at the loss of a lover. As Malaurie croaks out the final notes, the room is silent and her eyes brim with real tears. She is living this song. She holds our silence for 10 more seconds. Then the audience goes wild.

It's the closest I'll get to how Piaf must have been. I slip out and wander across the ancient cobbles, to Sacré Coeur with its glittering view of the city in the night. An accordionist starts to play a haunting refrain. It is "La Vie en Rose".

Travel essentials

Getting there

Jonathan Lorie travelled as a guest of Eurostar (08432 186 186; eurostar.com) from London St Pancras to Paris Gare du Nord. Return fares from £69.

Staying there

He stayed courtesy of l'Hotel (00 33 1 44 41 99 00; www.l-hotel.com), which offers doubles from €295 (£246), room only; and of Le Burgundy (00 33 1 42 60 34 12; leburgundy.com), which has doubles from €420 (£350), room only

Eating there

La Coupole (00 33 1 43 20 14 20; lacoupole-paris.com). Prestige menu, €56pp (£47), including a glass of champagne.

Visiting there

Carolyn Nin's show Hymn A Piaf is at the Théâtre de l'Essaïon in Paris until 9 November It then transfers to London's Hippodrome on 15 November (carolinenin.com).

Au Lapin Agile (00 33 1 46 06 85 87; au-lapin-agile.com). Admission €24 (£20), including a drink.

Le Lido (00 33 1 40 76 56 10; lido.fr/us).

Admission €95 (£79) for show and champagne.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments