Cyprus: Bordering on splendid isolation

Forty years ago this summer, Cyprus became a divided island. Julia Buckley strays across the Green Line to explore the once glamorous, now deserted, north

The Mediterranean gleamed salmon pink in the morning sun alongside my hotel, the sand crumbled between my toes and the air was so still that I could hear the wing beats of the sparrows skitting across the beach. It was the perfect resort setting, I decided. Or, rather, it would be, were it not for the neighbours – a macabre ghost town of derelict skyscrapers filing down the sand as far as the eye could see.

On the north-east coast of Cyprus, Palm Beach isn’t your standard resort; it’s a political hotcake at the centre of an unresolved war and four-decade power struggle. And the Arkin Palm Beach – my five-star hotel, which came with impeccable service, Molton Brown toiletries and views stretching towards Syria – is the last hotel standing.

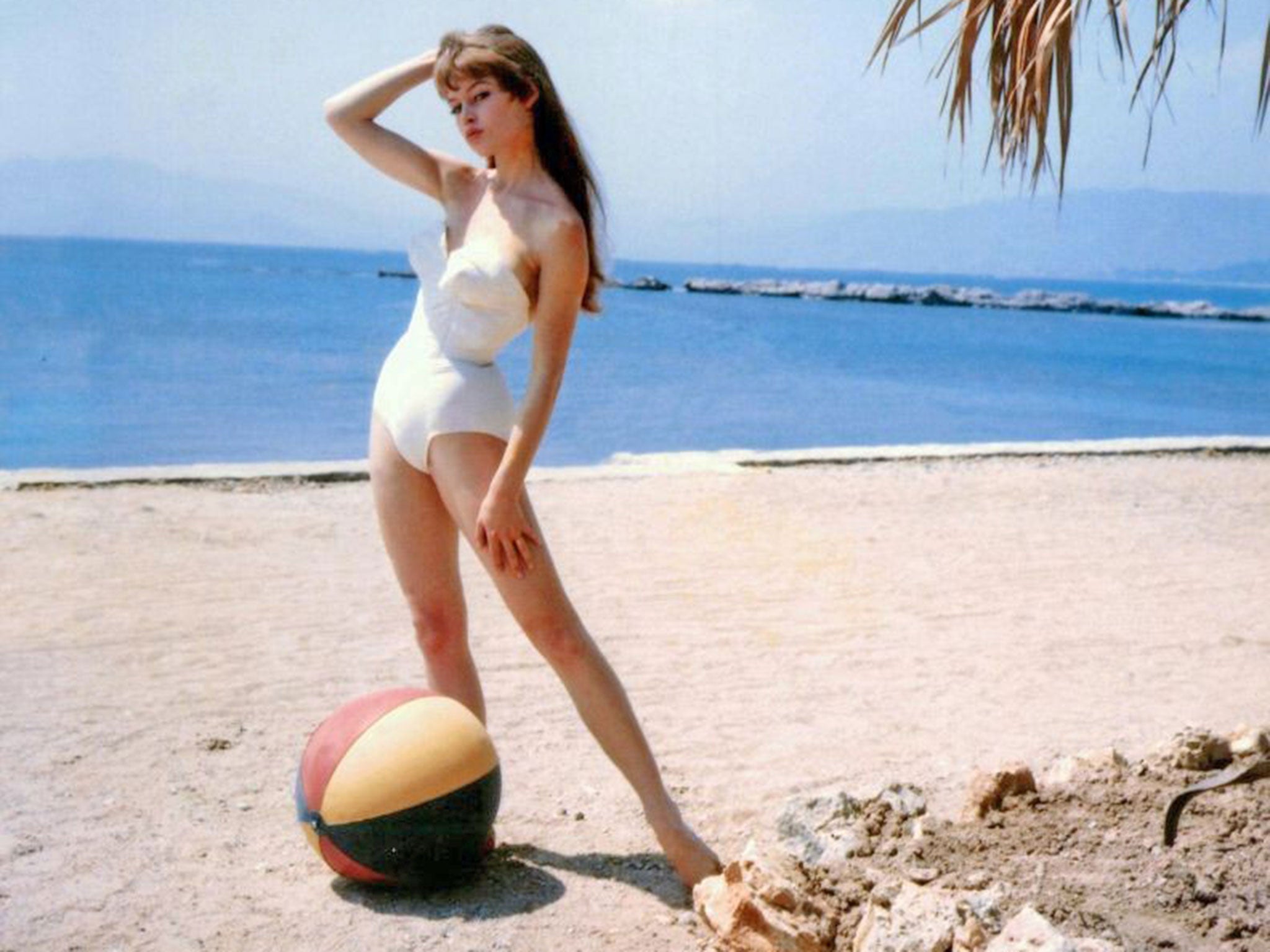

In its 1960s heyday, Varosha – a modern annex to the ancient walled city of Famagusta – was known as the Vegas of the Med. Tourists flocked to its pristine sand, while the likes of Brigitte Bardot and Liz Taylor cemented its glamorous reputation. Famagusta, meanwhile, was the most visited city on the island, thanks to its architecture (centuries of conquerors have left their mark on the city) and its panoply of early churches.

But everything changed on 20 July 1974, when the Turkish army invaded Cyprus. Greek Cypriots – Varosha’s main population – fled to the south of the Green Line established by the UN. Four decades on, Famagusta’s walled city is crumbling, if elegiac; its diminished population lives among abandoned houses and a minaret crowns the Gothic cathedral. Varosha, meanwhile, has spent 40 years occupied by the Turkish army, its buildings fenced off and left to rot. Imagine Tenerife through an apocalyptic filter and you have an idea.

Visiting North Cyprus – either the self-styled Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, or the occupied part of Cyprus, depending on who’s talking – isn’t a decision to be taken lightly. Turkey is the only country to recognise this self-declared state and the story of the past four decades is a heart-breaking one of atrocities on both sides giving way to displaced populations, carpetbaggers and the destruction of national heritage.

I went with moral misgivings; I left utterly bewitched. The northern part of Cyprus shares the climate, coastline and history of the south; but globalisation has almost entirely passed it by. With no direct trade, there are no international brands. The pace is slower, the tourists fewer, and, apart from the Kyrenia area, it has largely escaped the overdevelopment of the south.

The Karpas peninsula – the “panhandle” of the north-eastern tip of Cyprus – is a 43-mile sliver of dazzling, untouched coastline with waves pounding the cliffs on one side, dune-buttressed beaches on the other. In between, the rolling countryside is punctuated by sleepy villages, wild donkeys and the occasional goatherd. I’d gone to Karpas to follow its trail of six ancient churches. Cyprus has a long Christian history – St Paul is said to have made the island his first stop on his mission to spread Christianity and his companion St Barnabas is supposedly buried outside Famagusta in a still-preserved rock tomb. In a state which has seen most of its churches shuttered, looted or converted into mosques, Karpas is unusual in that not only has it allowed some to stay open, but the “church loop” is actively promoted.

Not that many tourists visit – in April, I had the peninsula almost entirely to myself. At Ayios Philon, a ruined Byzantine basilica teetering on a rickety cliff, my only companions were two stray dogs; at Ayios Thyrsos, carved into the seawall, I was joined by two Cypriot Londoners who’d made a pilgrimage to collect holy water from a spring in the tiny church. At Agias Trias, I found myself alone on a hillside, wandering through a fifth-century basilica paved with an intricate mosaic of geometric shapes.

Never mind the fragrant orange groves, the seafront promenades and the astonishingly friendly people (incidentally, I’ve never felt safer travelling as a lone female). The region’s international isolation means that it loses out on cultural funding and the parlous condition of its heritage is why I’d advocate visiting. There are world-class sites here. They include Vouni Palace, a 2,500-year-old cliff-top Persian settlement and St Mamas church in Guzelyurt, whose 16th-century frescos are some of the few to survive post-occupation looting.

Yet, despite the best efforts of their caretakers, most seem in a precarious state. At Salamis, a sprawling ancient Greek city near Famagusta, columns lay piled up by the sides of barely trodden paths. It’s potentially as impressive as Olympia or Delphi – but it needs attention. It won’t, with any luck, always be like this. With another round of talks under way, Cypriots I met on both sides seemed hopeful that this time, finally, some kind of solution might emerge.

Meanwhile, they’re taking tentative steps themselves. While I was in Famagusta, thousands of Greek Cypriots poured over the border to take part in a historic Easter procession – the first to be held in the traditionally Turkish Old Town in 57 years.

And, as I crossed back into the Republic of Cyprus, transferring from a Turkish to a Greek Cypriot taxi, the drivers got talking. My Limassol-based driver announced he was originally from Salamis. The Turkish driver was from Iskele, the neighbouring town. “Give my love to my land,” said Simon, as they shook hands, then embraced. “It is the most beautiful place on Earth.”

He wasn’t wrong. The minute I’d crossed the Green Line, I wished I was back.

Getting there

Non-stop flights to Ercan airport in the north of the island are banned from anywhere except Turkey. Turkish Airlines (0844 800 6666; turkishairlines.com) and Pegasus (0845 084 8980; flypgs .com) fly from a range of UK airports via Istanbul. Larnaca airport, the island’s main gateway, has more flights and is a 50-minute drive from Famagusta. Crossing the border is simple (there are no visa requirements). Airlines flying from the UK include British Airways (0844 493 0787; ba.com), Cyprus Airways (00 357 223 65700; cyprus air.com), Monarch (0333 003 0100; monarch.co.uk) and easyJet (0843 104 5000; easyjet.com).

Staying there

Arkin Palm Beach (00 90 392 366 2000; arkinpalmbeach.com): doubles start at €110, with breakfast. Oasis Hotel, Karpas (00 90 533 840 5082; oasishotelkarpas.com). Doubles from 80TL (£22), with breakfast. Bellapais Gardens, Kyrenia (00 90 392 815 6066; bellapaisgardens.com). Doubles 246TL (£68), with breakfast.

Touring there

Julia Buckley travelled with Green Island Holidays (020 7637 7338; greenislandholidays.com), which offers a week’s half board at the Arkin Palm Beach, and flights with Pegasus from Stansted, from £699pp.

More information: welcometonorthcyprus.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments