Could the next total solar eclipse be the best ever?

Book your trip and get your solar specs to watch the moon's shadow stripe across the US on 21 August 2017

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Top of the Eclipse Playlist at Nashville Music City is “Ain’t no sunshine” by Bill Withers. The Tennessee state capital is the biggest city on the “line of totality” of the first total solar eclipse to cross the US for 99 years.

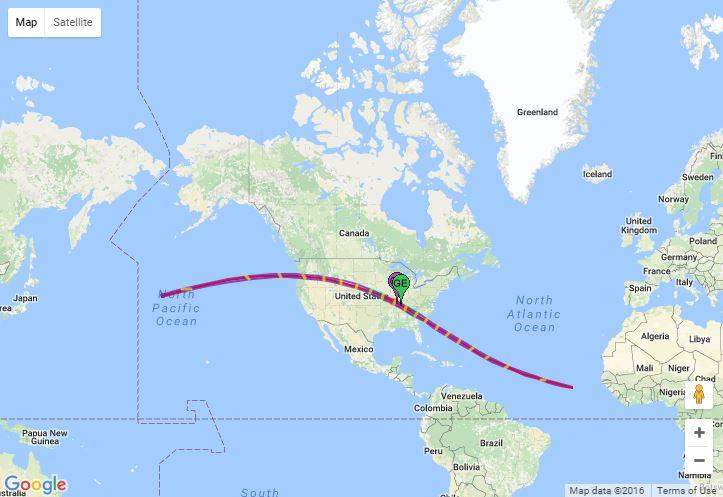

On 21 August, the track of the eclipse sweeps across the nation from Oregon on the Pacific coast to South Carolina on the Atlantic shore. It may trigger the biggest single movement of people for the purposes of tourism in human history.

An infinitesimal proportion of all the people who have ever lived have witnessed a total eclipse - but now the possibility is open to anyone lucky enough to be of modest means in the West.

You may have witnessed the partial eclipse visible in the UK in March 2015. At the time, I asked mild-mannered and formidably brainy astronomer John Mason to define the difference between a partial and a total solar eclipse: “The difference between a peck on the cheek and a night of passion,” he said.

That analogy helps to explains why, when I last spoke to the distinguished applied physicist at the time of the 2015 event, he was in the Svalbard capital, Longyearbyen (along with Mrs Mason).

Dr Mason had travelled to the world's northernmost town, along with a few thousand adventurers who had paid astronomical sums to be on the “line of totality” of the only total solar eclipse that year. They had a fine view, though the odds of clear skies had been assessed at only 50:50.

I’m partial to a total solar eclipse myself, but I prefer better odds.

Eclipses are entirely predictable: we know the stripes that the next few dozen will paint upon the surface of the Earth. But the weather is not. Four dimensions influence the choice of an eclipse site, and the most critical is the record of cloud cover for the corresponding date in previous years. The next: the degree of difficulty reaching the venue. For both of these, the lower the better.

That’s why, in 1995, I joined Dr Mason and about 100 other sky-gazing tourists in India. We watched the light go out amid the ancient Moghul ruins of Fatehpur Sikri near Jaipur, a short train ride from Delhi. My notes of the event read:

“As the heavens reveal their winning hand and darkness steals the day, we watchers, like the birds, fall silent. The meek old moon demonstrates its momentary power to suppress the sun in a gesture of cosmological contempt that lasts a few minutes but will live with you forever.”

Another devotee on that trip was Brian May, the Queen guitarist. It’s a kind of magic, the way that eclipses happen.

“The moon is not an important astronomical body,” my textbook tells me, dismissively.

Normally the Earth’s satellite contents itself with providing us earthlings with tides, light and somewhere to aim space rockets. But roughly once a year, it aligns with the sun and, thanks to a geometric miracle, blots out the hub of the solar system.

After a warm-up of over an hour, during which the moon creeps over the surface of the sun, totality hits like a hammer to still nature and man. Stars and planets emerge, blinking, in the middle of the day. Faint diamonds known as Baily’s beads - light from the sun slipping through lunar valleys - peek out from behind the moon to testify to the weirdly perfect fit, from a human perspective, of our two most familiar heavenly bodies. A sight to behold - so long as you can see it.

You may recall the 1999 European eclipse, which clipped a corner of Cornwall and had the Bohemians in rhapsodies, I took a cheap day trip on the ferry from Newhaven to Dieppe. The French port was the easiest place to reach from south-east England along the line of totality. While the pebbly beach was hardly the stuff of travel dreams, the seafood restaurant was heavenly. But the gods did not smile upon us, and the event was obscured by clouds. The Cornish contingent fared no better.

Next month, you can make your own astronomical luck. The 2017 total solar eclipse will roll across America like a mighty highway connecting state capitals. The path of totality sweeps over Salem, Oregon at 10.19am; Lincoln, Nebraska at 1.05pm; Nashville, Tennessee 25 minutes later; and Columbia, South Carolina at 2.44pm. Four minutes later, the moon’s shadow will take the shine off the beautiful colonial town of Charleston before dwindling into the Atlantic.

Citizens of Portland, Salt Lake City, Denver, St Louis and Atlanta will be within a few hours’ drive of the line of totality. With so many big cities so close, the 2017 eclipse is likely to persuade millions of people to move into the line of totality.

There’s a fair chance many of them will be disappointed. It might be that traffic congestion obstructs their journey, or they observe the profound astronomical phenomenon from the car park of Walmart. Or, as thunderclouds rumble across the Midwest and south-east US, the skies may be overcast.

So Dr Mason will be in the Rockies. Many parts of the western and central states have clear skies in August, so the final decision on where to view the eclipse was down to aesthetics. Jackson, Wyoming, is in a scenic area, and has the advantage of being close to the Grand Tetons and Yellowstone National Park, which adds to the pre-eclipse interest.

The moon may be “a dead ball of stone, its face encrusted with craters from ancient impacts with interplanetary bodies,” as my textbook says, but it will bring the summer of ’17 to life. It’s all in the roll of the cosmological dice.

Parts of this story originally appeared in a feature published on Independent.co.uk on 20 March 2015. You can read Simon Calder's original story here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments