The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Exploring Uruguay, the world's most successful footballing nation

Never mind the Euros, this diminutive South American country has a footballing history that outshines any other

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Uruguayan football is a miracle”, my guide Nacho tells me, “we have less than three and a half million people and 15 Copas América – more than any other country – two Olympic titles, two World Cups… That’s unique. Brazil alone has over three million registered footballers… That’s our whole population!”

And it’s true: Uruguay is without any challengers the most successful footballing country in the world, per capita. No other country this size has come even close. OK, its last World Cup win was in 1950 – the Maracanazo, when it inflicted a Brazilian national disaster by winning in Rio – and the national team failed to make it past the group stages of last month’s Copa América (the Americas’ version of the Euros) when they were beaten by Venezuela. But Uruguay has continued to produce great players, and has never, ever been a soft touch. Even without Luis Suárez, whose biting ban from the last World Cup ended in March, the current national team have been near the top in South American qualifying for the 2018 World Cup.

Football tourism has taken off in Argentina, with a Boca Juniors game often featuring on must-see lists. Argentina’s football is big and brash, but tickets are expensive, and due to fan violence away fans were banned (except tourists) from games until last September, so the atmosphere was often strange. For anyone alive to football romance, and who likes to feel the life of a country, Uruguay is frankly much more fun.

Fanáticos Fútbol Tours is currently the country’s only specialist tour agency, run on a suitably Uruguayan personal scale by Nacho Beneditto and Franco Pérez. With the aid of friends and local journalists, all football nuts, they provide a great insight to Uruguayan football culture.

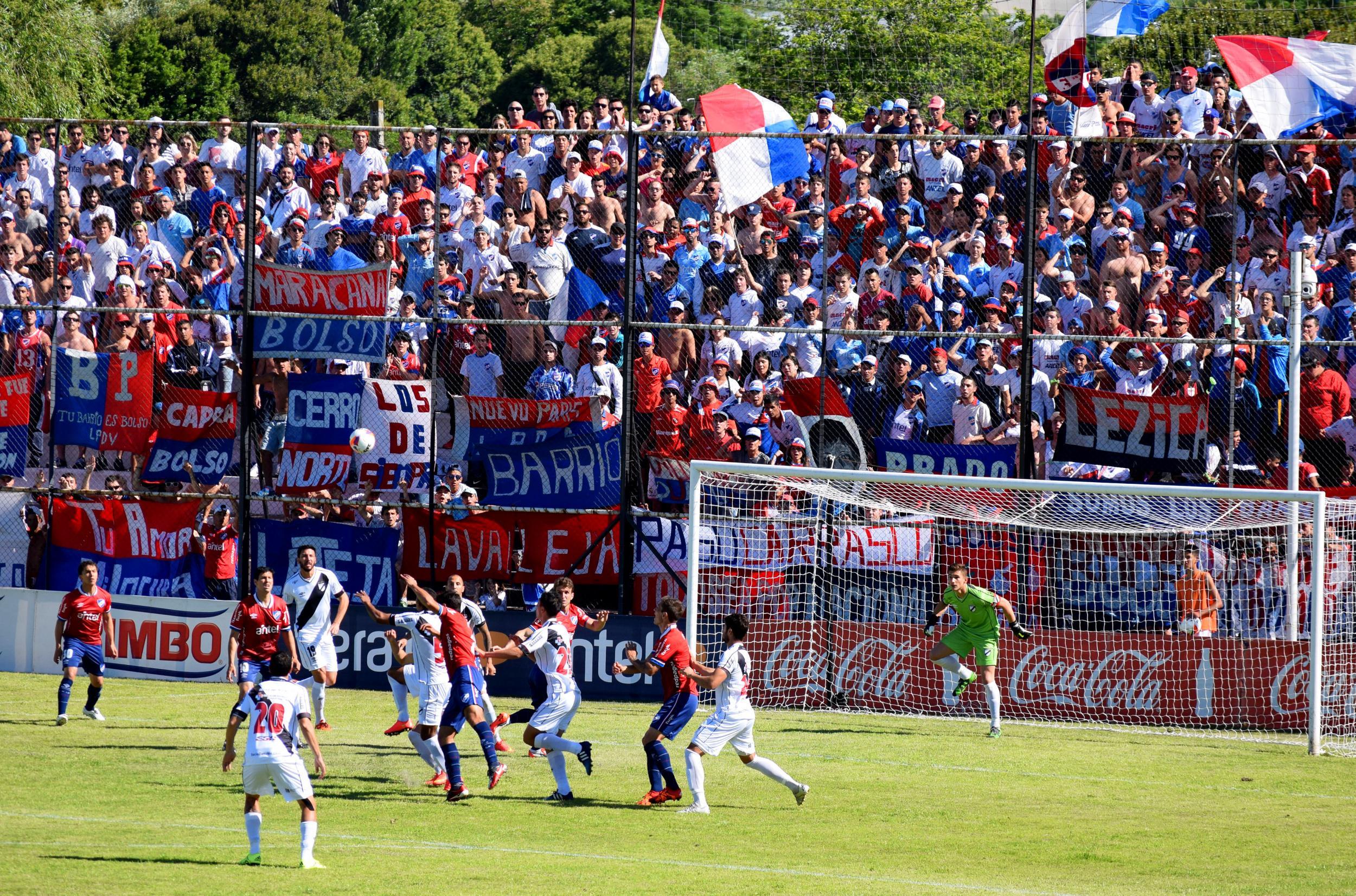

On a bright Saturday afternoon I drove through Montevideo’s northern suburbs with sports journalist José Gallo, with no sign of a football stadium in sight. Although Montevideo is home to around only 1.3 million people it’s a sprawling city, with rambling barrios or neighbourhoods of single-storey houses interrupted by empty grass. A larger-than-usual tree, a few police vans and cars pulled up every way possible announced that we were there, at the Jardines del Hipódromo or Racecourse Gardens, home of Danubio FC, who were due to play a giant of Uruguayan football, Nacional. Inside, the Jardines pitch is a dip in the ground surrounded by low-ish stands, with a capacity of around 18,000. Sticking out of the stand on the far side is a palm tree. There are only hard concrete seats, and no lights, no clock, not even a scoreboard.

And yet, this basic operation is the home club of Edinson Cavani, now at Paris-St-Germain, José María Giménez (Atlético Madrid), Cristhian Stuani (Middlesbrough), and more. So many great players have come through Danubio’s youth teams that the club’s shirts proclaim it the “University of Uruguayan Football”. Danubio has also won four Uruguayan league titles, the last in 2014. And once the game started the skill and energy levels were electric. The home fans’ raucous banging of drums, clanging percussion and singing segued from dumpa-dumpa-dum into something to the tune of “Bad Moon Rising”. Plus, the home team-underdog won, with a goal in each half.

One of many curiosities of Uruguayan football is that of 16 clubs in the First Division, around 13 are always from Montevideo, so much of the league consists of inter-barrio derbies. This sometimes bubbles over into violence, but on nothing like the level seen in Argentina, and the troublemakers are easy to avoid. In the main stand at Danubio, the multi-generational crowd were charmingly friendly. Two veterans, José Luis and Delfino, explained that, compared to a bigger team, a barrio club “is another kind of affection, a different pleasure”.

It’s not that Uruguayan football is any sort of egalitarian democracy. Uruguay’s “old firm” are Nacional (blue, white and red) and Peñarol (black and yellow), whose clashes are its clásicos, and which dwarf every other club in the country. TV rights are held by the cable channel Tenfield, owned by Paco Casal, the “super-agent” who also dominates sales of Uruguayan players abroad. Tenfield are only interested in games involving the two grandes. There are also plentiful stories of corruption.

The state of most smaller teams is “precarious”, I was told by Juan Pablo Aguirre and Jorge Rivero, who run a fan radio station set up to counter mainstream media disregard for their club – Liverpool FC, engagingly listed in papers as Liverpool (U), for Uruguay, in case anyone thought that other Liverpool might have nipped down for a game. Clubs are loaded with debt, players are paid late or never, some clubs “can’t even pay for water to fill the bath”. Producing good young players and selling them on is essential for a club’s survival.

The enigma of Uruguayan football is that, with all these aggravations, it’s still good. “Lesser teams” are never a pushover, and the grandes have to struggle to maintain their status. “In adversity”, Juan Pablo mused, “Uruguayan players are rebellious, and like to shut people up”. This is the celebrated garra Uruguaya – literally “claw”, but meaning commitment, edge, energy – the same intensity that leads the national team to play above its supposed level and also feeds into another known feature of Uruguayan footballers, their occasional tendency to go over the top. So matches are very competitive.

I saw the other scale of Uruguayan football the next day when Peñarol played Montevideo Wanderers. Big in every way, Peñarol have just inaugurated their own brand-new stadium, but until very recently played at the national Estadio Centenario, also the venue for all Uruguay’s home international games. Built for the first World Cup in 1930, the Centenario is a giant concrete bowl, dominated by a spectacularly tall, thin Art Deco tower, the Torre del Homenaje. Close to 100,000 people packed inside it for the 1930 final, but current capacity has dropped to around 60,000. There was a massive wall of sound from the black-and-yellow Peñarol hordes, going through an endlessly changing song book. Pots of mate, herb tea, were passed round, and there was a rich whiff of marijuana, decriminalised in Uruguay in 2013. The crowd were chatty, excited, if a little fidgety, since Peñarol, though top of the league, had been faltering. And, true to Uruguayan form, Wanderers, a slick, well-organised side, scored first, and Peñarol were only able to scrabble a late draw.

At Uruguayan games you can see great players who have returned from their European travels, such as, at Peñarol, Diego Forlán, still placing corners with majestic precision at age 37. At the other end you have first sight of young players who in a few years will be linked to multi-million euro price tags. Danubio currently have a lightning-quick 17-year-old, Marcelo Saracchi.

Uruguayan football is also full of great stories, the historic threads of an immigrant nation. Peñarol began life in 1891 as the CURCC or Central Uruguay Railway Cricket Club. Danubio – Danube – was so named by the Bulgarian-born brothers who founded it to remind their mother of home.

On one side of the Centenario is Uruguay’s Museo del Fútbol. Football museums are often routine, with their trophy cabinets and interactive exhibits. Montevideo’s stands out for its epic quality, above all in its celebration of the greatest Uruguayan side, which won Olympic Gold in Paris and Amsterdam in 1924 and 1928 and the first World Cup in 1930. On one wall are declarations by Pedro Arispe, a member of that team, which have to go among the great football quotations: “For me”, he said later, “my homeland was a place where I’d been born by accident… It was the place where I worked and where I was exploited… But it was there in Paris, where I realised how much I loved it… It was when I saw the flag go up the highest mast!… Then I felt what it was to have a country.”

Travel Essentials

Getting there

Iberia (020 3684 3774; iberia.com) flies to Montevideo via Madrid and TAM (0800 026 0728; tam.com.br) via São Paulo. From Buenos Aires, Buquebus (buquebus.com.uy) ferries sail twice daily to Montevideo.

Staying there

Don Boutique Hotel, Montevideo (00 598 2915 9999, donhotelmontevideo.com.uy). Doubles from U$3,300 (£85/$110).

Visiting there

Fanáticos Fútbol Tours (futboltours.com.uy). League and international matches with enthusiastic guides, and historic tours. The season has two halves, apertura and clausura (opening and closing), with a break for the summer.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments