Colombia’s ex-Farc guerrillas are training as coffee growers and baristas in Cauca

After Farc signed a peace agreement with Colombia’s president in 2016, former fighters are re-finding their feet

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

“I want Colombia to be different,” says Jhon Benavides, an aspiring barista and, from the age of 14 until last year, a guerrilla in the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc). He’s just prepared a brew, carefully weighing out freshly ground coffee beans before making some cups of arabica grown here in Popayán, an agricultural town in the department of Cauca.

The 28-year-old married father-of-two has been living in Resguardo Pueblo Nuevo zona veredal de paz – one of three rural United Nations-managed demobilisation zones set up for 400 ex-rebels who downed weapons after Farc signed a peace agreement in November 2016 with Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos in Caldono, Cauca. A Farc stronghold during the 53-year conflict, Cauca’s fertile, volcanic land that soars to 2,100m above sea level has earned its place as Colombia’s fourth-largest coffee-growing department, with 95,000 hectares under plantation, microlots farmed by 93,000 families. In 2016, however, another 36,000 hectares were dedicated to coca, according to Insight Crime, also making Cauca Colombia’s third-largest cocaine cultivating department.

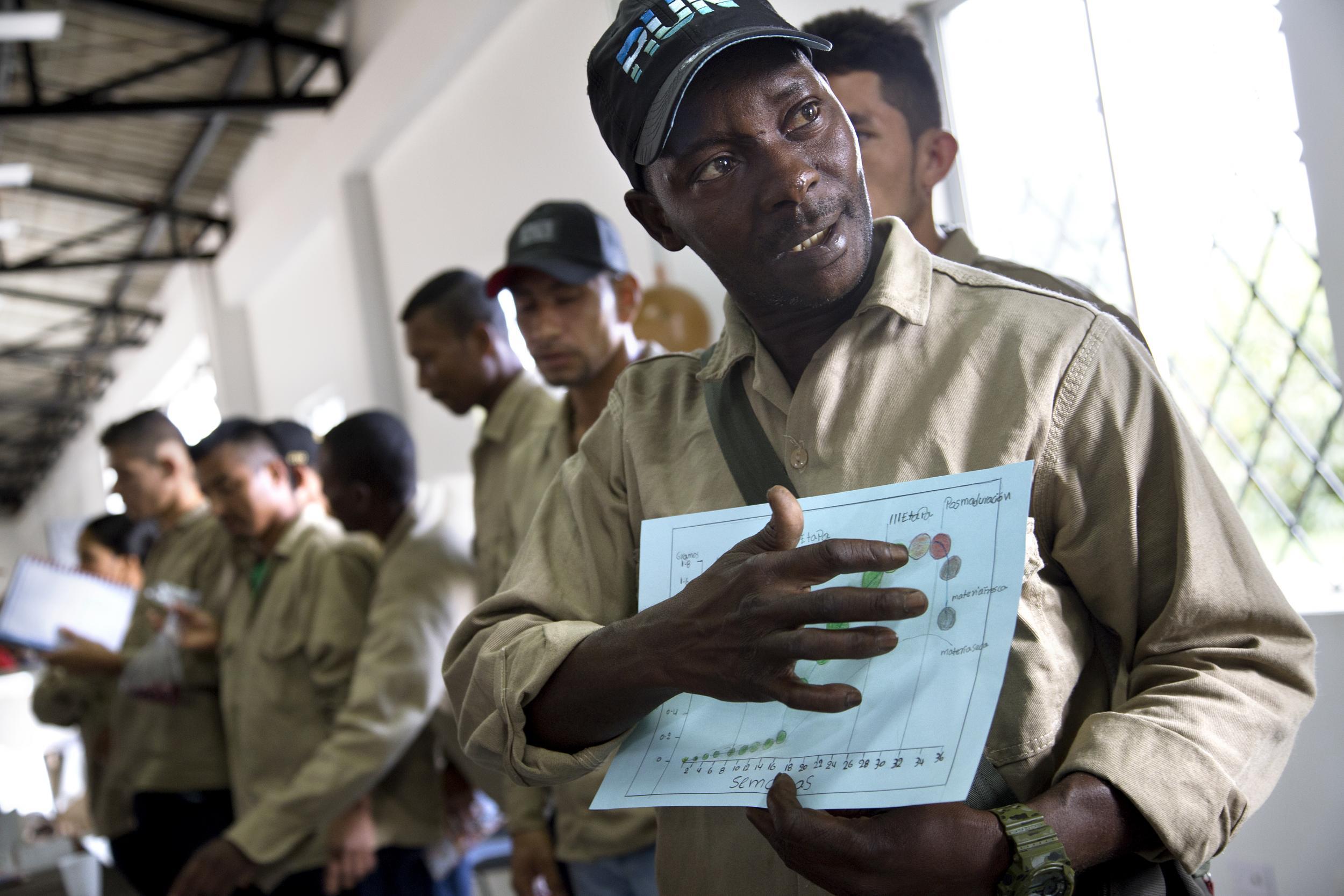

Jhon is now an apprentice on a scheme hatched to create a different Colombia. Following several interviews, he and 29 former guerrillas, including two women, were moved from Caldono to Popayán two weeks ago, selected to undertake a three-month coffee growing training programme at Tecnicafé coffee technology park. This is the first such scheme to kickstart former guerrillas’ reintegration into civilian life in Cauca. Supported by several organisations, including Colombia’s National Learning Service (Sena), National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC), and Illy Caffè and its local supplier Ascafé, the students live and breathe the training programme. There are four to a dorm and all meals are provided; one condition of the programme is that participants can’t leave Tecnicafé for the duration.

Dressed in jeans and the camel-coloured shirt he wears to class, Jhon, enthusiastically preparing the coffee with a Chemex maker, tells me: “It seemed a good idea to join this programme as I wanted to learn more about coffee growing. I want the best for my family and for my community.”

Jhon’s family purchased a small coffee farm four years ago, he says, but he hasn’t been able to get involved. “Farc imposed rules and norms so if I had left, [they] would have come to find me. I’d visit, but sporadically. It wasn’t safe and I had to anticipate that.”

He’s not the only one leaving behind his loved ones to study; Nancy López’s boyfriend is caring for their toddler. Born into a coffee-growing family with a six-hectare estate, Nancy could have made a decent income from Arabica – instead she joined Farc aged 11. Now that she’s realising coffee’s potential – and her own, at the age of 23 – the vicious circle will hopefully be broken.

Nancy says: “There was conflict at home when I was younger and joining Farc was a way out. I wasn’t very mature and didn’t think about the consequences.

“I started this course a week after my companions as I had to make arrangements for my daughter; I can call her every day. I haven’t been to school much and I don’t know much about growing coffee. But training is worth the effort for those of us who live in the countryside to learn about producing quality coffee. I wanted to take advantage of this opportunity; they don’t come around often.”

Jhon, Nancy and their fellow students don’t yet know that Illy Caffè has committed to buying the green coffee (pulped and ready to roast) they grow via Ascafé as part of the Italian roasting company’s sustainability commitments in Colombia. Fortunate because he already owns a finca, it seems Jhon’s enthusiasm and thirst for knowledge will ensure he progresses quickly in this new career. Other muchachos (“guys”, as Farc rebels refer to themselves), however, are less certain about the future. One, who wished to remain unnamed, said: “I don’t own any land and I don’t have the money to buy some, either. I’m not sure what I’ll do after this course; I don’t want to work as a coffee picker.”

A second commitment these students are unaware of is an eight-million-peso government stipend (£2,027) they will receive on completing the course; a one-hectare farm in the Popayán area costs around 60 million pesos.

This initiative is in its infancy, but the outlook is positive. “It’s very new but this is historic,” says Carlos López from Ascafé. “Coffee is a way out from the conflict and can help these people return to society. We’re giving them the knowledge to produce quality coffee: we have to join together so we all reap the rewards.”

Driving the green winding road from Cali to Popayán, it’s hard to imagine that war and conflict dominated this mountainous land covered with arabica bushes, banana trees and sugarcane just eight months ago. While the peace deal was struck only recently, Tecnicafé’s air is filled with hope – hope that coffee can be foundational in creating a peaceful Colombia. Jhon shares that sentiment.

“When I finish this course, we’ll harvest our coffee cherries in November – I can’t wait to bring them to Tecnicafé to be tasted.” As for the long term, he wants to be a great barista. “It would be a mistake to return to what I used to do. Just being here, reintegration, I’m starting to understand why I mustn’t go back.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments