The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Chicago: City of skyscrapers, Mies Van Der Rohe, and now an Architectural Biennial

This autumn is the perfect time to explore the city's architectural heritage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two chunky slab blocks tower over me. They make me think of giant bars of chocolate, but they're actually flats. These twin buildings are ideologies made of glass and steel. The not very catchy sounding 860-880 Lake Shore Drive glower at Lake Michigan, separated from the chilly water by an all-American freeway. The apartments – built in 1951 – are the embodiment of Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe's guiding philosophy of “less is more”. Just a steel frame wrapped around some windows, they're simple, elegant, powerful. At the same time they're also the embodiment of America's guiding philosophy of “more is more”. They're huge, their shapes and materials are unnatural – this is man's victory over nature; a place that cost a pile of money to build and costs a pile of money to live in. A property developer made it happen as much as a German émigré architect. It's a bag of contradictions – but then so is Chicago, the city Mies called home for the most successful part of his life. I look up at those apartments and wonder what it's like to live there. Architects can't make homes, only normal people can.

Mies never really considered himself “normal”. Born in Aachen in 1886, he was convinced of his own talents and that he was going to change architecture. In many ways, he lived at the worst of times. In 1933, the Nazis closed the Bauhaus Design School in Dessau while Mies was director. Hitler wanted the stupid pomp of Albert Speer's plans for Germania – a Berlin containing the biggest Neoclassical buildings in the world. Mies's stripped down Modernism was seen as socialist, though the man himself was anything but. The Nazis gradually forced him to leave Germany, although he did enter government architecture competitions while Hitler was in power – evidently he wasn't so morally repulsed by the Nazis' politics that he wouldn't work for them.

In 1937, he left for Chicago. And so in some ways he lived at the best of times – the third quarter of the 20th century was the period where architects were at the height of their powers, especially in the United States where they were trusted to build a newer, better, cleaner world. Chicago loved its acquisition and the Martini-drinking German couldn't wait to get started.

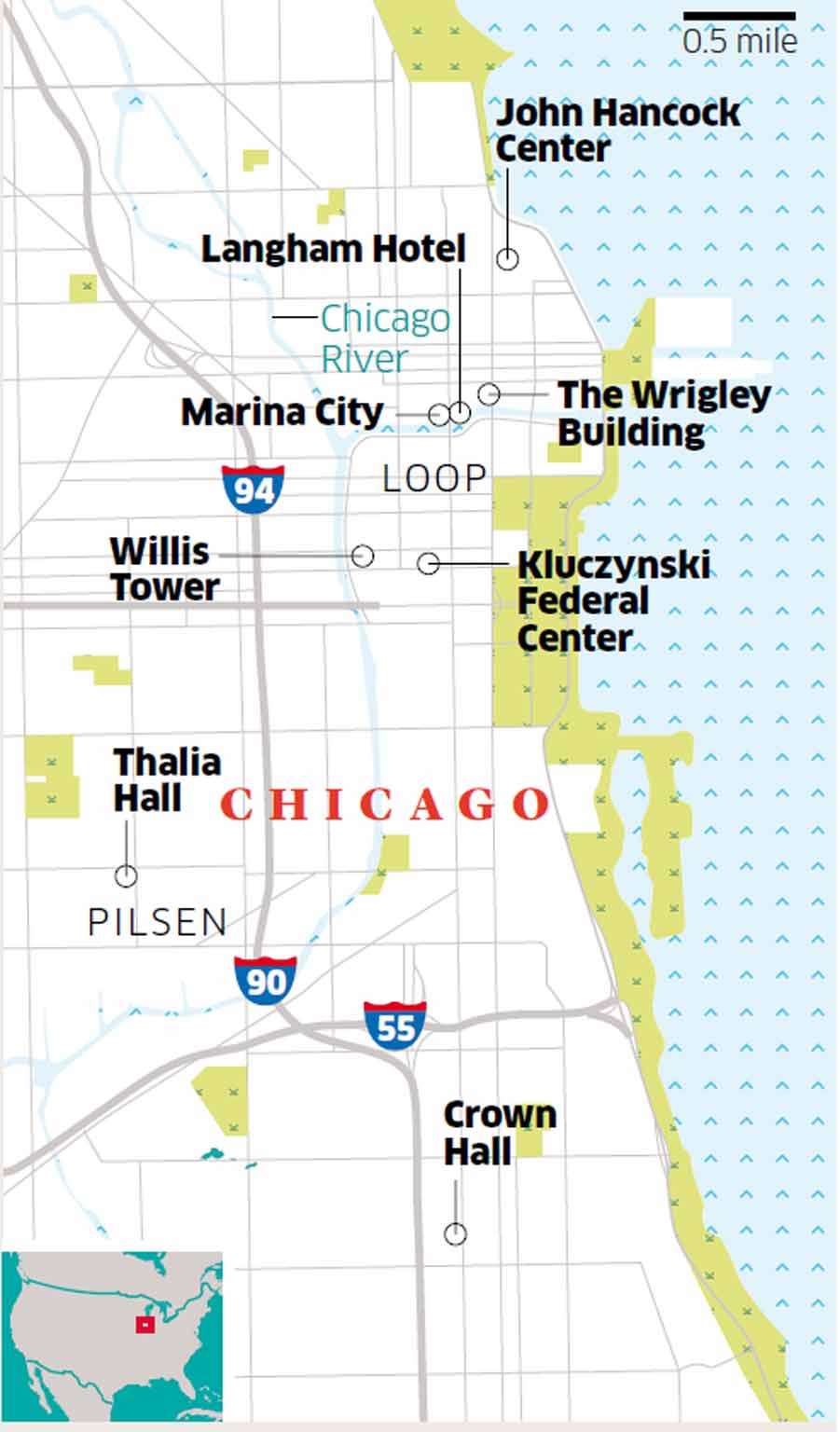

Mies was hired by the Armor Institute to head up its architecture department where he taught and drank. Armor had rebranded as the Illinois Institute of Technology; after the war, Mies was tasked with building a new campus, a couple of miles south of Downtown Chicago. Crown Hall, finished in 1956, is the centrepiece. It's stripped-down and unsparing with just a series of skinny columns holding up a giant roof space. If you let your eyes go fuzzy, its outline could almost be an abstract version of Batman's head, with two ears poking upwards.

Today, Crown Hall is still used by IIT architecture students. On a busy autumn morning, the campus looks beautiful and rational. In a way the black buildings, the green shrubs, the white walkways and the grey gravel planting trick me into believing that I might be in Japan.

This autumn is the perfect time to explore the city's architectural heritage because the inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial has just started. There are special events and exhibitions, by British wunderkind David Adjaye among others, while those ITT students have designed a one-off pavilion for the festival, a kind of 40ft tower of oversized ice hockey pucks that sits by Lake Michigan. The Biennial is a big deal in a city where architects are spoken of with a reverence usually afforded to rock stars.

Skyscrapers were born here in the 1880s after the Great Fire of 1871: steel-framed towers that created the stereotype of the American cityscape. My favourite is the handsome terracotta Chicago Building on Madison Street. Starchitects of their day – such as Louis Sullivan at the start of the 20th century and Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1920s – followed with ornate buildings that laid the groundwork for Mies and the rest.

Architecture is also a Freudian power game that men play. Mies smoked cigars and designed priapic towers, he sought to dominate the land like so many other men who came to America. Chicago was built on the sweat and ideas of Central Europeans such as Mies – Slovaks, Poles, Lithuanians, Germans, Ukrainians. I feel keenly aware of this as I drink lager and eat duck at Dusek's, a restaurant attached to an 1892 music hall, Thala Hall, in Chicago's Czech neighbourhood, Pilsen – while jazz singer Gregory Porter plays a set upstairs. It's an immigrant city with immigrant values.

While he was working at IIT, Mies accepted the commission to build a summer house. Chicago's skyline of skyscrapers slowly vanishes in the rear view mirror as I head east, replaced by cherry-red barns sitting in Illinois corn fields. I end up at Plano, a little town with a few houses. One of these houses is very special. The Farnsworth House was built here in 1951 for Dr Edith Farnsworth. It looks a peach perched on the undulating banks of the Fox River, with autumn leaves of ochre and brown falling all around it. The house is pared back to the absolute basics. It's just a single room, and it seems to float on the lightest supports. I'm lucky enough to explore the house with custodian Maurice Parrish, an effervescent guide who, it turns out, is the father of London-based DJ Theo Parrish. Parrish explains that after Edith sold up, the house was bought by millionaire British property developer Peter Palumbo. And in a weird twist of fate, Palumbo's son, James, also became a DJ and started Ministry of Sound. As well as this Mies landmark, Palumbo “collected” houses by Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright.

I slice through the suburbs back toward Chicago, along Interstate 55, transfixed by the suburban sprawl. As I get closer to the city centre, the buildings get bigger and bigger. Back in the Loop (so-called because it's lassooed by a loop of elevated Subway or “L” tracks) is an overblown complex of government buildings Mies built in the 1960s – the Kluczynski Federal Center. A courthouse, post office, and federal offices form a massive wall around a barren, windswept plaza. Office workers hurry past a red sculpture – Flamingo by Alexander Calder – which rears up more like a scorpion.

Mies's final building in Chicago was the IBM Plaza on North Wabash. It wasn't completed until after his death in 1973 and is now known as 330 North Wabash since the computer company moved out. Today, this huge, looming tower is home to the Langham Hotel, where I'm staying, on the ninth floor, and constantly looking out at the city below. The Langham group enlisted Mies's grandson, the architect Dick Lohan, to transform IBM Plaza into a hotel and today it is opulent, the public areas featuring sculptures by Jaume Plensa and Anish Kapoor (whose Cloud Gate installation – a giant silver “oil bubble” – dominates Millennium Park). The hotel is right by the Chicago River and next door to the Wrigley Building, that monument to chewing gum from the 1920s which looks like a wedding cake and was renovated last year into fresh office space. On the other side are the 1960s Marina City apartments, which look like two cylindrical corn-on-the-cobs and have boat docks on the river – built by Bertrand Goldberg, who studied under Mies back in Germany.

The IBM Plaza heralded a flurry of copycat buildings in Chicago – America's true vertical city. There was the John Hancock Center and then the Sears Tower (officially called the Willis Tower, it was once the world's tallest building), both designed by Chicago's Skidmore Owings and Merrill. The views from the tips of both are outstanding. Some disparagingly called SOM “Three blind Mies” as their buildings looked increasingly inspired by his work, but without the pizzazz. Mies had created a blueprint for the kind of buildings we see all over Chicago, all over the US, and eventually all over the world: sleek, shiny skyscrapers. He was the German who built an American city.

Getting there

American Airlines (020 7660 2300; aa.com), British Airways (0344 493 0787; ba.com), United (0845 607 6760; united.com) and Virgin Atlantic (0344 209 7777; virgin-atlantic.com) fly from Heathrow to Chicago; American also flies from Manchester, and United from Edinburgh.

Travelbag (travelbag.co.uk) offers returns from Heathrow from £369.

Staying there

The Langham Chicago, 330 North Wabash Avenue (001 312 923 9988; langhamhotels.com/chicago). Double rooms start at $297 (£198) room only.

More information

The Chicago Architecture Biennial runs until 3 January 2016 (chicagoarchitecturebiennial.org)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments