The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How artificial intelligence is about to trigger an art revolution (that could be bigger than Impressionism)

Artists are up in arms with Google for using their art to train AI. But from the tensions and disputes a new artistic movement may well emerge, writes Anthony Cuthbertson

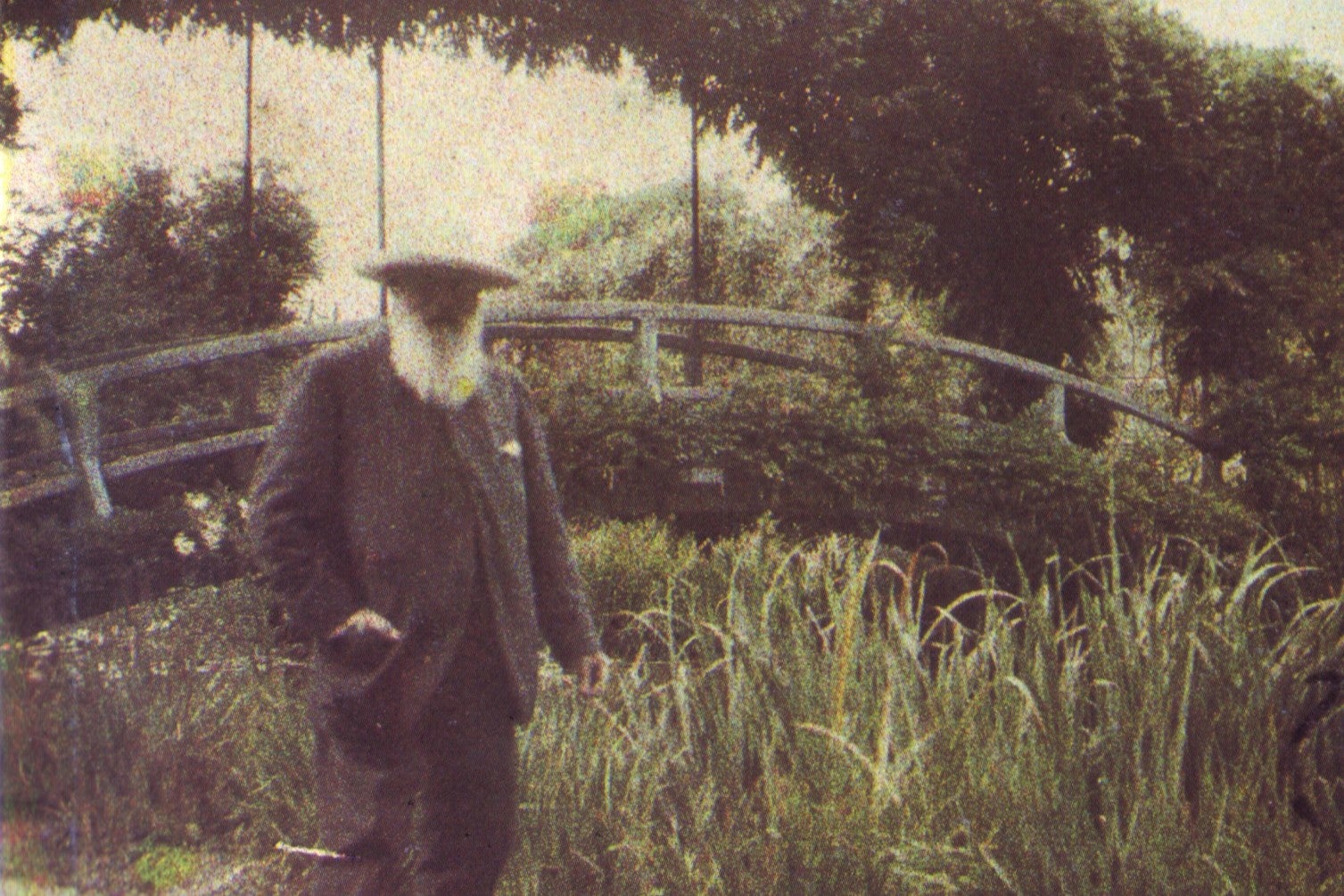

In 1872, Claude Monet sat down at his easel in Le Havre and painted what he would later call Impression, Sunrise. Critics initially mocked the painting for its visible brushstrokes and seemingly unfinished composition, but it birthed a movement that would revolutionise art.

Impressionism came in response to the emergence of photography, which offered the promise of replicating landscapes and portraits in far more realistic detail than even the most masterful painter. Now, 150 years later, artists are once again confronted by a new technology that is disrupting not just painting, but every artistic field.

Artificial intelligence is remarkable at generating everything from songs to videos at a prolific rate, and it is already proving to be both inspiring and infuriating for artists. This week, a group of photographers, cartoonists and other visual artists launched legal action against Google for allegedly using their work to train its AI image generator “without consent, credit, or compensation”. It is the latest of dozens of similar lawsuits.

However, a brand new human-led artistic movement may well emerge from these tensions and disputes. What the camera did for Impressionism could well be what AI is about to do for a coming art revolution.

In 2022, an AI-generated picture won an art prize at the Colorado State Fair. While some artists were indignant, the winner was unrepentant. “Art is dead, dude,” he told The New York Times. “It’s over. AI won. Humans lost.”

While many of the artworks used to train generative AI models such as Dall-E and Midjourney are by long-dead artists, others are by those who are still living. One artist whose name is frequently used in AI image-generator prompts is Greg Rutkowski, whose fantasy landscapes have inspired hundreds of thousands of AI-generated replica scenes, according to the website Lexica. All this new art is burying his original art in online search results. “I probably won’t be able to find my work out there because the internet will be flooded with AI art,” he told MIT Technology Review. “That’s concerning... It’s starting to look like a threat to our careers.”

Other artists concerned by this trend are joining together to try to protect their work. One of their requests is for Google to destroy its copies of their artwork. Thousands of artists have also signed up to use the tool Have I Been Trained? to determine whether their art is being used in AI data sets.

However, while some fear AI will make artists redundant, others believe it will make human art more valuable.

At around the same time as Monet and his peers were redefining art, a less well-known movement was forming on the other side of the Channel in response to the industrial revolution. Factories had made the creation of jewellery and tableware possible on an unprecedented scale, giving rise to the Arts and Crafts movement, which ditched the homogenous patterns and designs of the machine age.

People embraced it, favouring the handmade and personalised touch. Even if AI can create original masterpieces – and for now, generative AI can only replicate styles – people will likely still prefer art created by a fellow person.

In his new book, Deep Utopia, the philosopher Nick Bostrom outlines why sentimentality means that certain creative endeavours are impossible to automate. “A child’s work with crayons may be especially dear to its parents,” he writes. “This little labour might be harder to automate than the work of a neurosurgeon or a derivative trader.”

So while AI may not replace artists, it could force them to find a way to distinguish themselves from the technology. It may mean that physical tools such as paint brushes and chisels become favoured over the digital canvases popularised in recent years by artists such as David Hockney. Art forums on Reddit appear to be embracing this more traditional aesthetic, with artists sharing close-ups of their brushstrokes just to prove that their work was not created by AI.

Entirely new mediums of expression may even emerge, birthing a new artistic era as profound as impressionism. Art enthusiasts could also grow increasingly interested in the life story of a particular artist, to know what lived experiences inspired their creations.

Studies have already proved that humans prefer human-made art over machine-made art, even when it’s identical. Just like with chess – following the defeat of Garry Kasparov to IBM’s Deep Blue, people would still rather watch other people playing chess than watch computers doing the same, even if they are worse at it. It is something that appears to be innate to the human experience. For example, it seems hard to imagine the public’s attention being caught by an AI song battle in the same way as it has by the recent rap feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake.

It will therefore more likely be a form of collaboration, not competition, that emerges between AI and artists. Just like the impressionists used photographs to help with their sketches, artists will use AI to assist in their work. It will accelerate the creative process, lead to entirely new art forms, and challenge existing concepts of authorship and authenticity.

Unlike photography and Impressionism, this technological reckoning will affect not just painters, but filmmakers, authors, video game developers, musicians, architects, fashion designers – and even photographers.

Ultimately, AI will redefine what is considered art, and how art is created, and could even force us to rethink what it means to be human. In his seminal work The Creativity Code: How AI is Learning to Write, Paint and Think, the Oxford University mathematician Marcus du Sautoy concludes that whatever comes next, human-created art is not going anywhere. “My journey,” he writes, “has not produced anything that presents an existential threat to what it means to be a creative human. Not yet, at least.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks