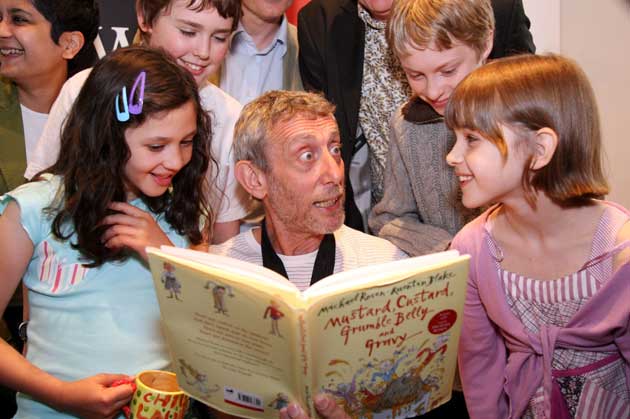

Chapter and verse: Michael Rosen on why it pays to study children's literature

Michael Rosen tells Michael Prest how studying and teaching creative writing set him on the road to becoming the Children's Laureate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Are you still in touch with any of the class of '68?" asks Michael Rosen, as we plod back from the Tube to my house. I mutter about having been in contact recently with Christopher Hitchens, the journalist, about revisiting our old school together. Then a vivid image from that time at Oxford flashes through my mind. A huge hairy face is thrusting itself through the window of a car. Inside, just leaving a debate at the Oxford Union, is Michael Stewart, the then Labour foreign secretary. "What do you think about Vietnam, then?" bellows the future Children's Laureate.

The image is still with me as we settle down around the kitchen table, me with my umteenth cup of coffee for the day, Rosen with a glass of Thames Water's finest vintage. Why, I ask, did he – when already a successful children's writer and performer – embark on graduate work? No more effort is needed now than 40 years ago to get him talking.

"I do my English degree at Oxford and then I start writing plays and writing poems. The poems get taken up by the Eng Lit world. Suddenly, I find myself in the Eng Lit world, which like any other coterie has its institutions, its book clubs and so on – and of course education itself," he swiftly recaps.

By the mid-1980s Rosen was making a name for himself performing his poems and stories in schools. In 1987 he became the presenter of Treasure Islands, a BBC Radio 4 programme about children's books but aimed at adults. The programme was axed by Radio 4's controller, James Boyle, on the grounds that it was "ghetto programming" – a description Rosen still deeply resents, arguing that there was and is huge interest among grown-ups in children's books.

But Treasure Islands set Rosen thinking. "At the time I was doing it, I kept thinking: our critical level is weak. I'm just winging this basically. I like this or that because of what? I'm drawing on the resources of my English degree from 20 years earlier, but surely life has moved on. There's a whole new critical theory for adults, but isn't anything happening in the children's book world?"

It is big business. About 10,000 children's books are published in the UK annually. Some of the most enduring and best-selling books – from Alice in Wonderland to Harry Potter, have been written for children – with one eye on adults as well. Feeling increasingly inadequate about how he approached his own work, as well as that of other writers, Rosen took an MA in children's literature at the University of Reading in 1992.

The degree helped him to see how and why Kids' Lit should be subjected to critical rigour as much as grown-up writing. "Children's literature occupies a very different position from literature as a whole, largely because of two things: it's part of nurturing, in the anthropological sense, but it's also part of education. You can't say that of any other kind of literature," he says.

Rosen was oddly placed. On the one hand, he was continuing with his "shows", his monologues for schools, which he calls "kids' standup", drawing on Stanley Holloway, the great music hall performer, and his real hero, Billy Connolly, the comedian. On the other hand, academia beckoned. He began teaching about children's literature on the MA in education studies at the then University of North London, which later merged with the University of East London to form London Metropolitan University. Then he received The Call.

Professor Jean Webb from University College Worcester called Rosen out of the blue and suggested he should do a PhD. Webb is now director of the International Centre for Research in Children's Literature, Literacy and Creativity at what has become the University of Worcester. Because Worcester could not then award degrees, the PhD was done under the joint auspices of Worcester and UNL, where Rosen continued to develop an MA in children's literature.

The UNL degree was possibly unique in the UK at the time. It was open to anyone with a creative or design background. The idea was to present a project – on which the student had worked – and put it in its theoretical, design or creative context. The concept was interpreted liberally. Rosen remembers that a civil engineer who had designed a bridge explained why and how he had done it. "I went with a proposal that I would write a book of poems – which had been brewing in my mind anyway – and that I would set it in its theoretical context – namely, how did I come to write it, what kind of decisions did I make as I was writing and why, and how did I make these decisions? So it was an historical, sociological, textual view of how I came to write," Rosen says.

The book was to become one of Rosen's best known, You Wait Till I'm Older Than You. Many of the poems were drawn from his childhood – a vital part of understanding his own writing. Rosen was born in 1946. His parents were Jewish, teachers and Communists. Along with many others, they moved out of the East End, where their immigrant ancestors had settled, to North-west London – in the Rosens' case, Pinner in Middlesex.

His parents grumbled about the suburbs, and the dispersal of their Yiddish-speaking community. "I thought the suburbs were brilliant", says Rosen. "There were parks. My mates were there." As he read about the changes in post-war British society and ploughed through modern critical theory, Rosen began to see how his PhD was making him more aware of his own writing and its context. "I asked: 'How come I lived where I lived?' I wrote a poem about my backyard. But how come I'm there?"

The questions led to much greater self-consciousness in the strict sense of the term. "The sort of things I discovered through doing the PhD enabled me to contextualise what I was doing, how conversations at home which I reproduced in the poems had come about," he says.

Rosen's analysis of the somewhat complacent prevailing attitude to children's books hardened. "The main body of criticism to do with children's literature was informed by a kind of antiquarianism," he says – and then laughs. "I'm as antiquarian as the next. Find me some book from 1850 smelling of mould and I want it." Children's books, he argues, came from parents, in the twin senses that they were selected and written by adults. The process tended to be circular: parents wrote and selected books as they remembered the ones they had as children. The small amount of work on children's literature was in magazines such as School Librarian and occasional newspaper reviews.

For Rosen, it seemed that too much discussion of children's books was abstracted from any concrete context. Behind any child's book or theory of children's literature is a view of children and their upbringing. But conventional views took little account of the circumstances in which the book was written and certainly did not embrace modern critical theory, such as the work of the French social critic, Pierre Bordieu, who emphasised the idea of social reproduction: the background a child brings with him or her to school affects their relationship with the printed page.

At a practical level, there was the question of the availability of children's books. "There was a tradition in the children's literature world that talked about this stuff as though it was universally available, universally read – the great classics such as Treasure Island. They weren't," Rosen says with feeling.

But when you write, Rosen argues, you internalise an audience. A time-worn phrase such as "once upon a time" actually belongs to an intertext – criticism-speak for the sea of texts in which a particular text lives. That raises very tricky questions about who controls the text and sets limits on it – who is the arbiter of taste? Rosen is adamant that it should not be left to the Daily Mail. He cites the case last year of Jacqueline Wilson, the well-known children's writer and former Childrens' Laureate, who was forced to change "twat" to "twit" in her book My Sister Jodie.

Rosen has strong views on the episode. "That was a debate that should have been engaged very robustly by the children's book world. Hands off! Leave her alone!" He maintains that "twat" was a perfectly acceptable word in the context used and is what children call each other. However, the relative weakness of the theoretical understanding of children's literature left the field open to the conventional understanding of children's books as safe and sensible.

While he has become something of an evangelist for the advantages of mature writers doing graduate work to improve their understanding of their craft and children's books. Rosen recognises that PhDs are not for everyone. He cites the example of Maurice Sendak, the American writer whose book Where the Wild Things Are has been an international bestseller since publication in 1963. "I doubt he worried about the things I worry about. Some people are so brilliant, they just have the world of story inside them. I take my hat off to that."

Rosen's quest for self-awareness continues. He finished his PhD in 1997 and has been helping to set up an MA in children's literature at Birkbeck College, London. It is probably more than many of the class of '68 have achieved.

Courses in children's literature

University of Bolton

Canterbury Christ Church University

University of Central Lancashire

Kingston University

University of Gloucestershire

University of Winchester

University of Worcester

University of Reading

University of Roehampton

University of Sunderland

Bath Spa University

Newcastle University (offers an optional specialism in children's literature)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments