RWC 2015: Are big hits delivered by ever-bigger players ruining the game?

On the eve of the World Cup, Independent on Sunday rugby writer Hugh Godwin asks whether the health of the players and the future of the game are worth the spectacular 'big hits'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Martin Johnson and George Gregan, the captains of England and Australia respectively, each spared a thought for their opponent in the interviews conducted immediately after rugby union's World Cup final of 2003 – won famously for the English by Jonny Wilkinson's last-minute drop goal – their civility in a moment of extreme emotion was not contrived by public relations. It was an instinctive expression of their sport's quintessential generosity of spirit and lack of self-obsession.

I am sure these qualities will be in evidence again as the eighth Rugby World Cup unfolds in England and Wales over the next seven weeks, leading to the final at Twickenham on 31 October. Huge audiences in stadiums and on television will bear witness to arguably the planet's ultimate team game. The players share an innate understanding of their interdependence – they know the job done by the hefty prop forward with his head buried in the gloaming of scrums and mauls is integral to the more slender fly-half passing the ball to his centres and wings in the open spaces. There will be respect for the referee and graciousness in victory and defeat. Feigning injury, as happens in football, is unacceptable.

Strange to relate, therefore, that there have been times in recent years when I have worried whether rugby's defining sense of selflessness might be leading to its destruction. Driven by a need to win – markedly accentuated since the game went "open" in 1995 and was played to earn a living, not just for fun – it has become increasingly a contest of collisions, less devoted to evasion and strategy. Players with freakishly large muscles honed by countless hours in the gym throw themselves into one shuddering impact after another. The timeless impulse of team spirit over individual glory today translates into "putting your body on the line". Another entry into the vernacular has been the "big hit", describing a tackle that slams an opponent backwards and disrupts his or her team's possession of the ball. If the tackler mistimes the contact – as Owen Farrell of Saracens did when he collided with the head of Bath's Anthony Watson in the Premiership final last May, forcing Watson out of the match with concussion – it may still be regarded as an accident, not worthy of a sending off. "There was nothing malicious in it," Farrell commented afterwards, and no one disputed him.

David Flatman, the recently retired England prop-turned-columnist and TV commentator, has a gift for authentically articulating the players' experience. "Knocking a ball carrier back puts the other team on the back foot, physically and psychologically; a nitrous injection that changes the game," he explains. "And it can be just as enjoyable to receive a hit. k You will see a guy stand up with a huge smile on his face after taking one. A great part of rugby's appeal is how savage it is. You can whack people legally – that's why people love it."

That goes for the spectators, too. Walking along the touchline at a Premiership club rugby union match last season, I paused to observe the crowd. Mums and sons, dads and daughters, groups of corporate quaffers. Then, behind me, a big hit that knocked the recipient over. "Whoa!" roared the crowd, and I noticed one man in particular punch the air and scream, "Smash 'em!" A quick search on YouTube reveals dozens of compilations of big hits, some interspersed with punches and bloody faces.

Defence has become more organised and ruthless. I once compared video recordings of a British & Irish Lions test match in 1971 with one from 2009 and there were three times as many tackles in the latter. And whereas tackles used to be made fairly passively from the side or behind, they are now routinely made head-on, with obvious dangers. Wales's match against Scotland in 2010 sticks in the memory as thrilling and depressing by lurching turns; it had a fantastic finish, full of tries and skilful attack, but there were also injured players littered around the turf. The worst affected was the Scottish wing Thom Evans, who had ducked into an opponent's pelvic bone and damaged a vertebra in his lower neck. Evans never played rugby again.

The dry statistics of the Rugby Football Union's annual surveillance project put the injury rate in the 2013-14 English Premiership season at 1.8 players per team per match, requiring an average of 26 days off to recuperate. Consider that for a moment: each time a team plays, one or two of its players needs a month off. They don't want to leave the pitch, nor to show weakness, but there is only so much the human body can take. One of the British & Irish Lions' tests in South Africa in 2009 ended with five Lions players in hospital.

Concussion is the most common among the wide range of rugby injuries. England's full-back Mike Brown and the Wales wing George North were stood down for months earlier this year, to recover from being knocked unconscious as they made try-saving tackles. The pace of the game makes accidental collisions unavoidable. Players also more frequently jump high for the ball at the risk of being tipped over on to their heads or necks. Medics patrol the side of the pitch, there are protocols to "recognise and remove" players with suspected concussion, and video monitoring was recently introduced to prevent an injury being missed. But while all this satisfies the duty of care, doesn't it indicate something is wrong? North was typically stoical in answering reporters' questions in the aftermath of his injury with the airy comment: "It's not table tennis, is it?" And of course no one – in adulthood, at least – is coerced into playing rugby.

Still, there is concern expressed from disparate sources. Allyson Pollock, a doctor who researched schools rugby injuries for 10 years after her son suffered a shattered cheekbone during a game, argued for contact to be taken out of youngsters' games. Stephen Jones, the doyen of current rugby correspondents, who works for The Sunday Times, wrote earlier this year of his worry that too much was being asked physically of the players.

Rugby's nearest professional equivalent in the US, American football, has suffered dreadful tales of suicides among depressed, brain-damaged ex-players. While he waited for his headaches to fade, Mike Brown was advised not to watch TV for long periods – ironic, it might be said, considering that his wages, estimated to be around £500,000, are due in large part to TV's desire to broadcast top rugby.

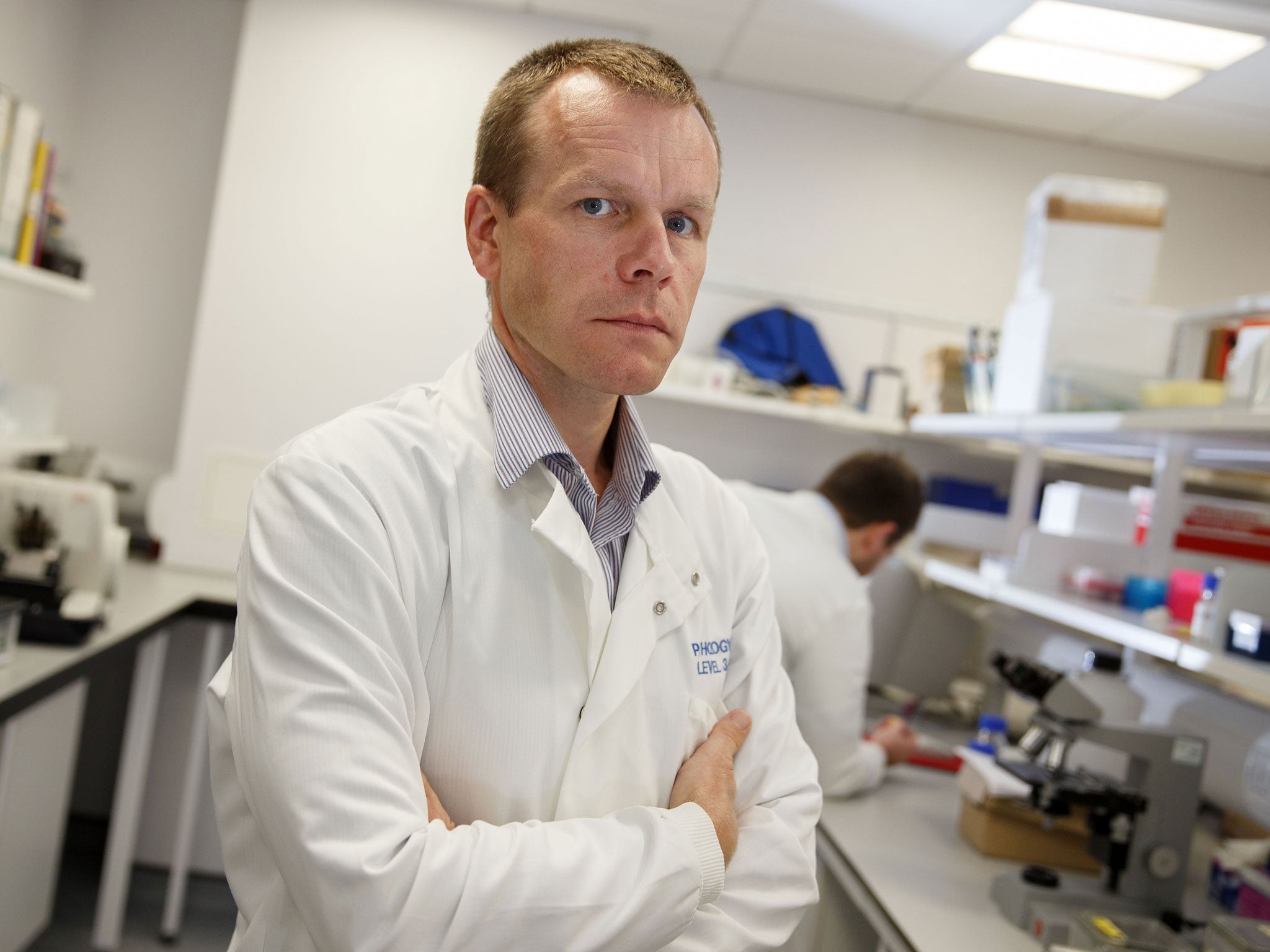

Dr Willie Stewart, a Scottish neurosurgeon who has studied rugby extensively, advises the global governing body, World Rugby. "People say they love the big hits," he says. "I'd rather see rugby survive and thrive than become some kind of super-heavyweight contest that only 18-stone robots play in a fairly limited pool of damaged individuals. The BBC, in the midst of this year's Six Nations Championship, produced a highlights package of the biggest hits. American football stopped doing that in the past decade, as it projected the wrong message. We should get the game back to something that truly everybody can play, where the whole team can have an expectation of walking off at the end of it."

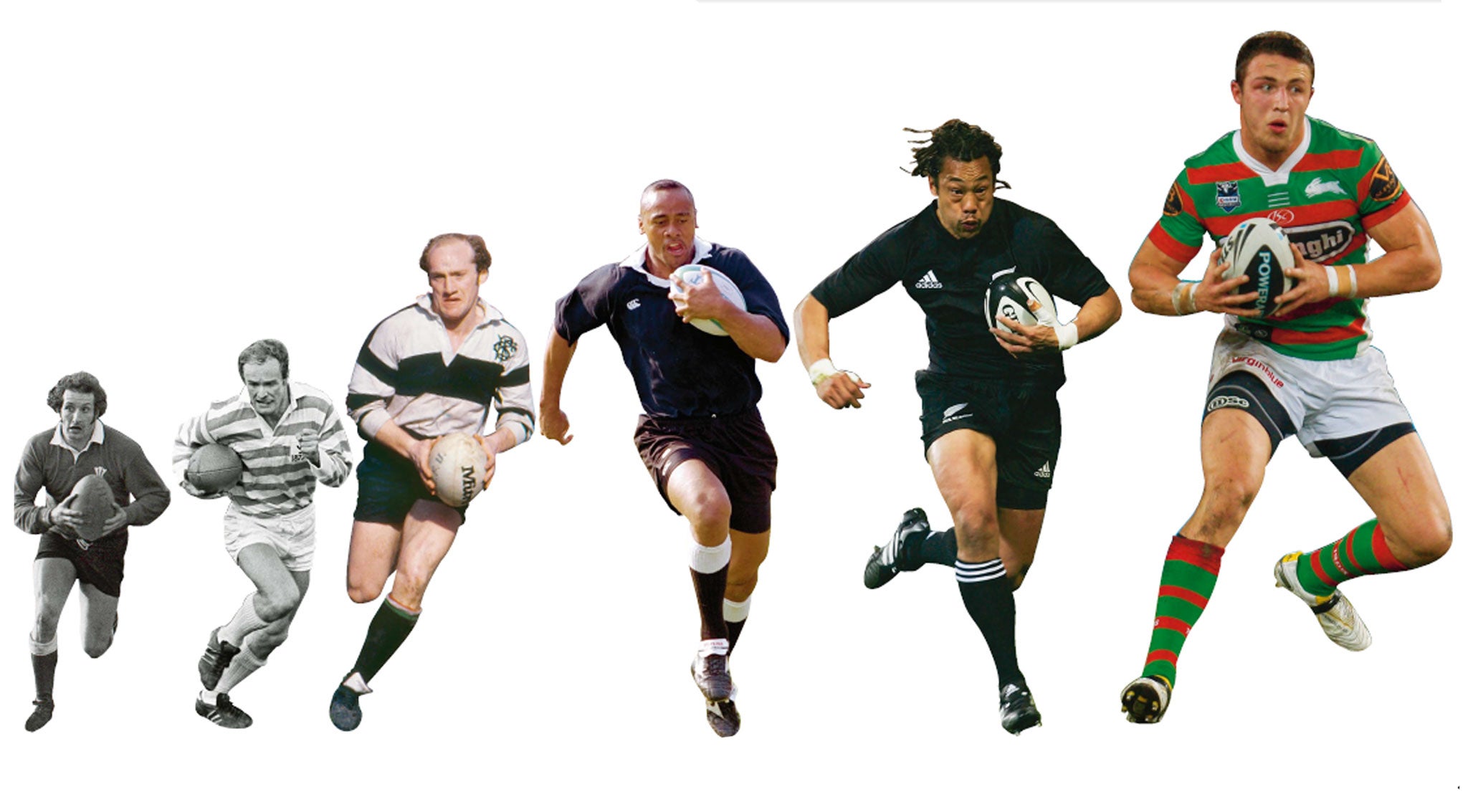

When England played France in a World Cup warm-up match at Twickenham in August, the home side's eight forwards – the bigger men in the overall team of 15 – had an average weight of 18st. Their counterparts of a generation ago, captained by Will Carling in the Grand Slam-winning match against the French in 1991, averaged 16st 3lb. Similarly, the England backs of 2015 – including the gargantuan recruit from rugby league, Sam Burgess – averaged 6ft 1.5in, and 14st 12lb; in 1991, they were more than three inches shorter, at an average of 5ft 10in, and more than two stones a man lighter (average 12st 10lb). "I was considered freakishly big and strong when I was 18," says Flatman, "but I was a weakling compared with a young prop now.

"The biggest issue is players wanting to be back on the field too quickly," Flatman adds. "I remember trying to cheat a concussion test once, and being proud of it. My club coach stopped me and said, 'Don't be a bloody idiot, take a rest.'"

Tom Rees played in the 2007 World Cup, and won 15 caps overall, as a fast-moving openside flanker of comparatively modest size; he might have been England's captain at the forthcoming tournament if he hadn't retired at the age of 27, in 2012, due to persistent injuries. (Even lucky players know their career will be over by their mid- to late thirties.) Rees is now midway through a six-year course training to be a doctor. He admits that rugby has grown to be more like American football: a power- and territory-based game of possession. Another analogy is with chess: you can try the subtle routes via the bishops and knights – or simply use the poor bloody infantry of pawns to barge opponents aside up the middle.

"Big hits often look far more impressive than they are dangerous," says Rees. "If you're on the receiving end, in most cases you'd be a bit winded, embarrassed, or both. The priority is to iron out the dangerous tackles – I saw one in a match in New Zealand when the player just planted his shoulder into the other guy's cheekbone. Players know the difference between what's acceptable and what isn't."

So what should rugby do to mitigate the fact that so many of its top players are injuring themselves in the simple act of playing the game? World Rugby has begun a study group comprising coaches, players, referees and medics, to consider whether the laws of the game need to be adapted – and safety is uppermost in their deliberations. Rees believes one useful tweak would be to oblige the tackling player to make contact at least a foot-and-a-half below the opponent's jawline.

There will be no changes before 2018, however, which worries Dr Stewart. "It shouldn't take another year or two's worth of thought," he says. "There are dangers at the breakdown [the action immediately after a tackle], when a guy comes straight over the top using his head as a battering ram, and with the tackles made without the arms, and when one or two players are in mid-air with no control over what happens when they land, unless they sprout wings."

Some observers feel that the England-France match of last March offered a possible way forward. With the English needing a stack of tries to win the Six Nations Championship on points difference, both teams abandoned some of the stodgier set-piece confrontation and unleashed a scintillating running game. England won 55-35, a record scoreline for the fixture. "That was amazing," says Dr Stewart. "True flowing rugby, not slugging it out in the middle of the park and winning on penalties at the cost of damaged players."

It was intriguing and uplifting to hear England forwards coach Graham Rowntree state recently that players don't need to get any bigger – a rare instance of someone from inside the professional bubble acknowledging the problem. Flatman concludes: "It is worth taking a while to think about where rugby is going. But we have to be careful of responding to people who don't care about the game, and who want to sanitise it." Or, as Rees puts it: "Rugby has given me a sore knee, sore ankles, and a sore shoulder – and I miss it hugely."

The Rugby World Cup begins on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments