The Saint finds a new mission as Southampton pay for their sins

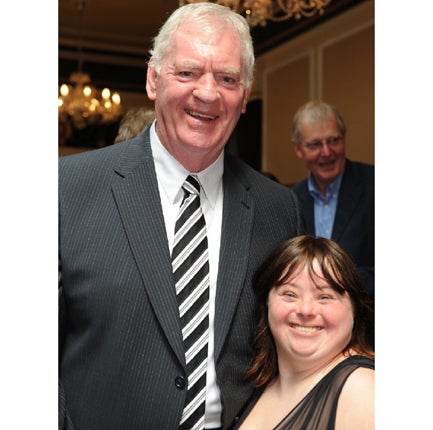

Manager without a medal finds his reward as cheerleader for young people with disabilities.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lawrie McMenemy MBE is a big man with big memories.

As a football manager his career embraced moments of humiliation, like getting the sack at Doncaster, and of hubris, like winning the FA Cup with Southampton by beating Manchester United. But, he says, nothing is etched more in his mind than the week he spent in Dublin six years ago watching thousands of young people taking part in a sports event that was special in every sense. This was the Special Olympics, designed to give those who have learning disabilities the opportunity to express themselves lucidly and bravely through sport.

McMenemy, now 72, one-time assistant manager of England and manager of Northern Ireland, who signed and nurtured some of the biggest names in football, Kevin Keegan, Alan Shearer, Alan Ball and Mick Channon among them, these days has his own special mission in life. "When I got the call to become associated with the Special Olympics, like most people I assumed it was Paralympics but when I went to their World Games in Dublin six years ago, it was a real eye-opener," he says.

"It really hit me what it was all about. I've always been one for the community. When I was in football I always believed that the game and the clubs should be an integral part of the community. It's not a question of being a do-gooder. If someone thinks it will help their cause by sticking my name on it, who am I to say no?

"In Dublin there were 80,000 people at Croke Park. The USA team's ambassador was Muhammad Ali, riding in a golf buggy. U2 were top of the bill with Riverdance at the opening ceremony and then Bono came on with Nelson Mandela. It was televised all around the world, except in Britain of course. I mean you can't interfere with Ant and Dec, can you? There were 8,000 athletes from 160 countries, and I am sat there going, whoa, what is this all about?"

Two years later McMenemy took over as chair of the Special Olympics of Great Britain. "I know that when you are dealing with the disabled, whether it is Down's Syndrome, autistic or whatever, some people are not comfortable with them but I found that having to live with the big names and the big stars made it easy because you treat people all the same. You have to win their trust and laugh with them because, as Jimmy Savile said to me once, 'If you don't have a laugh, you'll have a cry'.''

All this week there will be laughter – and doubtless a few tears – in Leicester as McMenemy presides over the Special Olympics GB Summer Games, the biggest multi-sports team event to be held in the UK before 2012. Some 2,700 athletes will take part in 21 sports in venues spread around the city.

"There are 1.2 million people in this country with learning disabilities, so it is good that they can be recognised through sport in this way," says McMenemy. "When they asked me to be chairman four years ago, I said, 'I'll do it but I'm not your orthodox chairman, but I will bang the drum and wave the flag and make people aware', and that's what I'm trying to do."

While he would not profess to be a Saint, McMenemy, of course, was one for much of his football life, which is why he has been saddened at the decline of Southampton. "You would never have dreamed a club like Southampton nearly went out of business. The problem was, when it became a plc it stopped being run the way it had been for a hundred years by people in the community who ran it for the supporters.

"I like to think that by winning the FA Cup, being second in the league and in the League Cup final, and having a little tickle at Europe, I did my best for a happy, professional outfit. But the way it started to be managed financially took it to the knife-edge.

"You are talking about a club which had two managers in 30 years, Ted Bates and myself, to one which had nine managers in three years and three in one season. Alan Pardew [the new manager], bless him, obviously has high hopes but the reality will set in on 8 August when you start playing in what is virtually Third Division football, minus 10 points."

Of the new regime, headed by Swiss owner Marcus Liebherr, he says: cryptically:"The indication is that these people are going to run it on tight business lines." Tight being the operative word. When McMenemy and his wife Ann arrived as invited guests at the pre-season friendly against Ajax last Saturday they found there was no regular parking space and had to park in a garage across the road.

Afterwards, the man who managed the club for 12 years, returned as their director of football and has the Freedom of Southampton, was told that from now on he will have to pay and watch from the terraces. No wonder he feels rather hurt. "The crowd gave the owner a good reception in his red and white scarf, but I just hope he'll be there to watch Carlisle United and when it's pissing down in November."

McMenemy is now vice-president of the League Managers' Association and is trying to get cup medals awarded retrospectively to managers and coaches. He tells how, in a League Cup final, he was tugged up to the Royal Box by opposing manager Brian Clough. "'Come on, young man,' he said, 'we are going to get something out of this.' I think it was the president of Uefa who was awarding the medals. He looked perplexed but they scrabbled around and gave us a box each. When we looked in them later, they were empty.

"I've got a grandson who idolises me, but one of my biggest disappointments is that despite all my years in football and all I've done, I haven't got a medal to show him." Over the next few days, Big Mac will be helping to hand out medals to other people's children and grandchildren who have been striving to overcome their personal handicaps through sport. And that, for him, makes it rather special.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments