Great Olympic Friendships: John Carlos, Peter Norman and Tommie Smith – divided by their colour, united by the cause

Norman 'was a man who believed right could never be wrong,' Smith said, turning to Norman’s family. 'Peter Norman’s legacy is a rock. Stand on that rock. Peter shall always be my friend. The spirit shall prevail.'

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

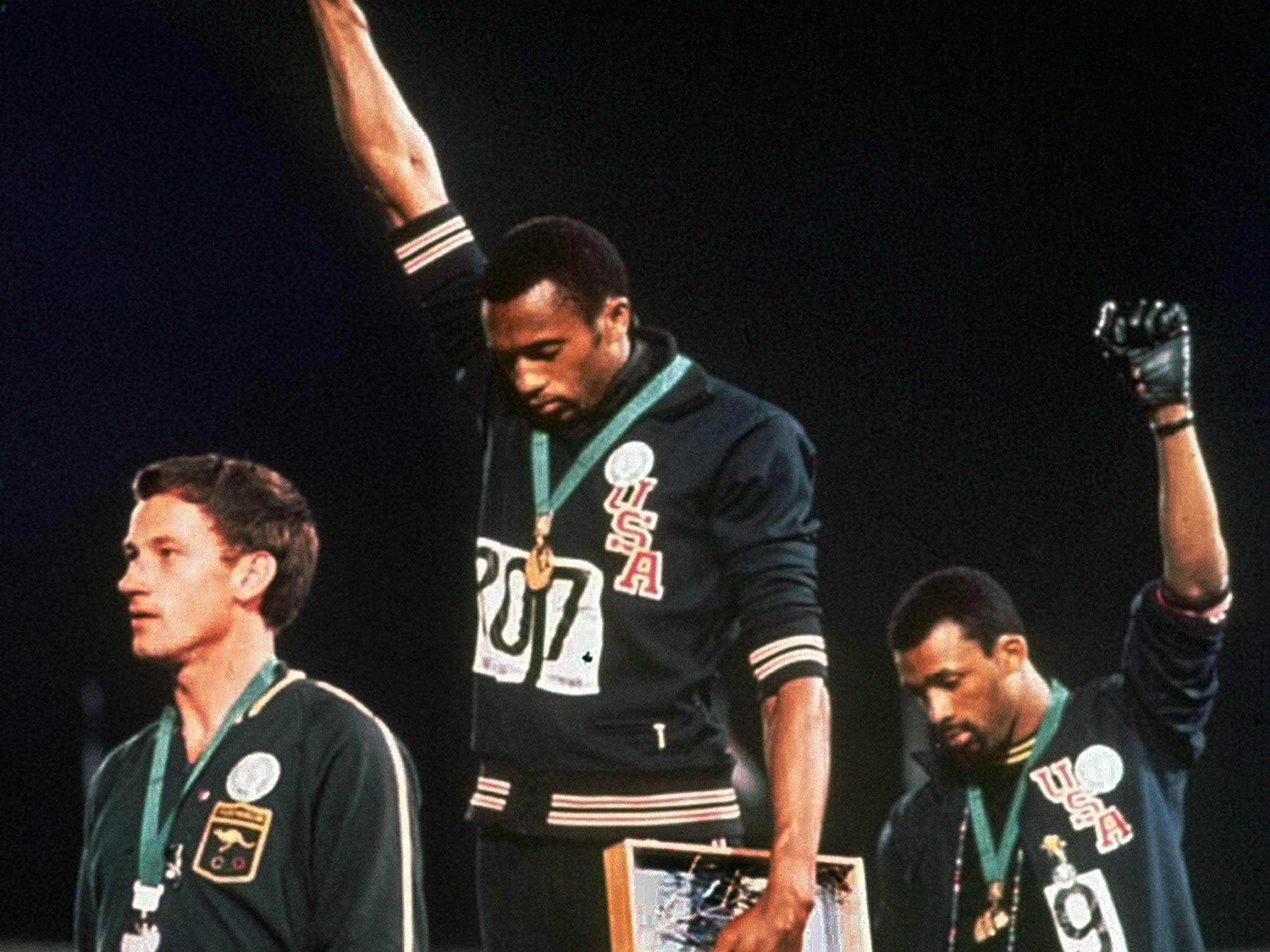

On the campus of San Jose State University in California stands a monument recreating one of Olympic history’s most unforgettable moments. It depicts Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two alumni of the university, giving their Black Power salute after the 200 metres final at the Mexico City games in 1968, in which Smith had won gold and Carlos bronze.

But the place on the rostrum for the silver medalist is empty. A casual visitor might think that is to allow visitors the perfect spot for a selfie, alongside two athletes forever synonymous with the African-American struggle for equal rights. In fact the omission does an injustice to an extraordinary friendship.

Peter Norman, who pipped Carlos for second place in virtually the last stride of the race, was just the white guy on the podium, overlooked as the world’s media focussed on Smith and Carlos, and the retribution visited on them by Avery Brundage, the American racist who was president of the International Olympics Committee at the time.

In 1968 the world truly seemed out of control. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated, Soviet tanks had brutally suppressed the Prague Spring, students had almost toppled the French government. And here were Smith and Carlos, bringing America’s crisis of race to the Olympics, the supposed sanctuary of brotherhood and love, where the world’s problems were temporarily put aside.

On Brundage’s orders, the pair were thrown out of the Olympic village and sent home. For years afterwards, their lives were ruined. But Norman too paid a heavy price. Back in an Australia that was practising its own discrimination against the aborigines and operating a whites-only immigration policy, he was ostracised and vilified for his involvement in the incident.

To this day, Norman’s 20.06 seconds in the Mexico final remains Australia’s 200m record. Yet he was passed over for the 1972 Games in Munich, although he had repeatedly met the required qualifying times. Even at the 2000 Sydney Games in his native country, he was virtually ignored by the Australian authorities. “If we were getting beat up,” Carlos said later, “Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone.”

Norman was no mere bystander in the indelible events of that 16 October 1968. He was a devout Christian, deeply sympathetic to the black rights movement, and by extension to the Olympic Project for Human Rights – an organisation founded in October 1967 by Harry Edwards, another San Jose State graduate, to use the Games to promote racial equality.

Smith and Carlos already wore the OPHR badge on their tracksuits. On his way out to the medal ceremony, Norman borrowed a badge from a member of the US Rowing Team to show his solidarity. And it was Norman who suggested that Smith and Carlos share the famous black gloves used in the salute, after Carlos left his pair in the Olympic Village. That’s why Smith held out his right fist while the US anthem was being played, while Carlos raised his left one.

Norman died of a heart attack in 2006, and Smith and Carlos were pall-bearers at his funeral. In his eulogy that day, Carlos explained exactly what had happened 38 years earlier. Just before the ceremony, the two black Americans asked Norman if he believed in human rights. He did. They then asked if he believed in God. Norman, who was from a Salvation Army family, told them that he did, strongly.

“We knew,” Carlos told the mourners, “that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat and he said, ‘I’ll stand with you.’” Carlos expected to see fear in Norman’s eyes. “I didn’t. I saw love….He never flinched on the dais, he never turned his eyes, he never turned his head, he never said so much as ‘ouch’. You guys haved lost a great soldier.”

Tommie Smith was no less heartfelt in his praise. Norman “was a man who believed right could never be wrong,” Smith said, turning to Norman’s family. “Peter Norman’s legacy is a rock. Stand on that rock. Peter shall always be my friend. The spirit shall prevail.”

Only after his death did Australia make amends. In 2008 Norman’s nephew Matt made a well-received documentary Salute, recounting how a modest white boy from Victoria got mixed up in one of the defining events of the civil rights era. In 2012 the Australian Parliament formally apoligised for his treatment and acknowledged his role in fostering racial equality. But the final word belongs to Peter Norman himself. “I guess,” he says in Salute with a twinkle in his eye, “I’d like to be thought of as an interesting old guy.” He was.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments