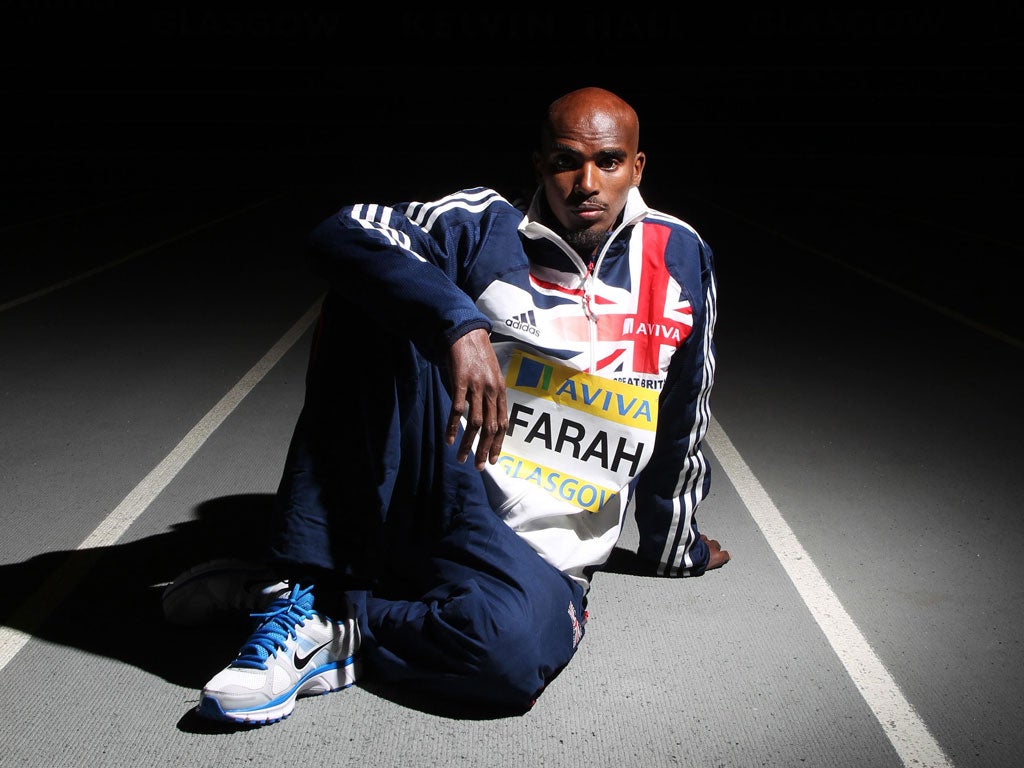

Mo Farah: Young man in a hurry

It's a long road from Mogadishu to Stratford, but the journey will be worth it if he can win tonight's 10,000m

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mo Farah has been here before. Four years ago in Beijing, he waited for a week while his teammates helped raise the roof of the velodrome, swam to victory in the pool, and began lifting a nation of perennial losers into the Olympic big league. And then the man with the only hope of ending one of the longest medal droughts in British sport ran in the 5,000m – and failed to qualify for the final. It was, he said, “the most disappointed I've ever been in my life”.

Tonight, Farah will lace up his spikes for his second shot at Olympic glory, in the final of the 10,000m. After four years in which he has transformed his approach to running, become a world champion and a father, Farah, 29, is among the favourites to win. A gold in that race, or in the 5,000m next week, would be a British first. And if winners need charisma and a compelling life story to become heroes, victory for Farah would do more than make history.

"Athletics is the number one event in the Olympics, and running is the number one discipline," says Farah's manager and agent, Ricky Simms. "For a guy as popular as Mo to win a gold on home soil in the Olympics Stadium... well, it would just be remarkable. Just as Usain Bolt became world famous in Beijing, this will be Mo's platform."

Simms speaks with authority. The Irish former runner, 37, manages Bolt too, and is credited with guiding the Jamaican from gifted 15-year-old to the fastest man in the world. He also represents half a dozen of Farah's rivals from Kenya and Uganda, but has a soft spot for the Brit. "Mo's the only person in the world I know who nobody has a bad word to say about."

Whatever happens tonight, the title of the nicest man in sport will be Farah's. Calm, funny, kind and generous, he is the antithesis of the chest-thumpers we watch in awe but struggle to relate to. But if his slender shoulders prove resilient under the weight of national expectation tonight, will they support the Bolt levels of attention Olympic victory would bring?

"Absolutely," says the man who perhaps knows Farah best. Alan Watkinson is the runner's former PE teacher turned mentor, confidant and best man at Farah's marriage to his childhood friend, Tania Nell, in 2010. "If he wins he'll spend a day or two being happy and celebrating and then get on with training," he adds. "If he loses he'll be sad for a day or two and then get on with training. That's how Mo works."

Farah's calm exterior conceals a hunger to win that took years to build. He says he was "born to run", but he never wanted to be a runner. Mohamed Farah was born in 1983 in Mogadishu. Muktar, his father, a British Somalian from Hounslow in west London had met his wife on holiday in Africa. Civil war soon forced the family to move north to neighbouring Djibouti. "We lived in a normal stone house," he said in 2008. "My grandfather worked in a bank and we had a comfortable life, not easy but not hard."

Farah was full of energy and mischief as a child and would not change when he moved to London, aged eight, to live with his father, who had come back earlier. (His mother would remain in Africa.) He could speak only a few phrases of English and, back then, football was his passion.

Watkinson remembers meeting an 11-year-old Farah at Feltham Community College in west London. "I was about to teach my Year 7 class how to throw the javelin," he recalls. "There are lots of safety procedures to go through and you'd like to think the children would treat it with a little respect. I looked up and there was Mo, hanging from the goalposts."

Farah won the javelin and pretty much every other athletics event at school. He was good at football, too, but it soon became clear his future lay in running. "He was very talented," Watkinson says. "He had a huge stride length and an effortless style ... but his talent was still very raw."

Aged 13, Farah came ninth in the English schools cross country. The next year, Watkinson promised him an Arsenal shirt if he won. He did, going on to win his first major title at the European Junior Championships in 2001. In the same year he joined the new Endurance Performance Centre at St Mary's University College in Twickenham, and a talent started to become a profession.

Simms had spotted Farah about two years earlier, at a junior cross country race. The challenge, as it would be with Bolt, was to manage the transition from junior to senior sport. Talent alone helped Farah to become Britain's top distance runner, but he didn't threaten a world stage dominated by East Africans. The stumbling block was his focus and ambition. The breakthrough came in 2006 when he moved into a house in south-west London with some of Kenya's top runners, who had always seemed untouchable.

"Mo would go to bed at 2am after hanging out with friends and sleep in till 11," Simms recalls. "I remember him coming to my office and saying, these guys go to bed at nine and wake up at six. Their whole approach was completely different and that was eye-opening. He had been happy to be the best in Britain, but living and getting to know these guys gave him belief he could do more."

After the disappointment of Beijing had faded, that failure gave Farah further motivation. He joined high-altitude training camps in Kenya and ran 100 miles a week. His times dropped and in 2010 he made another breakthrough, winning the 5,000m and 10,000m double at the European Championships. Later that year, Farah ran 5,000m in 12:57.94, breaking David Moorcroft's long-standing British record.

"I was delighted," says Moorcroft, who was later a BBC commentator and chief executive of UK Athletics. "I had waited 28 years for it to go and I'm glad it wasn't a one-off. For Mo it wasn't just a case of breaking a British record, but breaking into the ranks of the best in the world."

By now, Farah's success had already started to open gaps in his Somali family. "He doesn't really have a lot to do with them," Watkinson explains. "I've never really got to the bottom of it because he's very private. I think he was expected to immerse himself within that community, but Mo found that impossible to reconcile. There was no way he could commit to the amount of time they expected from him. So they drifted apart, but there's no animosity."

Farah's immediate family is much closer. His wife, Tania, had been a friend at school, but they became a couple in 2008. Farah has a stepdaughter, Rihanna, seven, and the couple are expecting twins in September. To at least ease the effects of the separation professional sport demands, Tania and Rihanna have moved to Portland, Oregon, where Farah trains with his coach of the past year or so, the maverick Cuban-born Alberto Salazar.

Farah credits his new coach and regime with his rise to the top, which he sealed with a stunning win in the 5,000m at the 2011 World Championships in South Korea, and a silver medal in the 10,000m. The anguish of Beijing finally laid to rest, Farah has become used to some of the trappings of fame, while never losing his boyish smile. He has sponsorship deals with Nike and Lucozade and last year launched the Mo Farah Foundation after a trip to Somalia.

In a world where medals are worth more than their weight, victory in London will ensure more sponsorship and donations. Farah has said he plans to move up to the marathon after London, an event to which experts have said he is perfectly suited.

But first, there's tonight, when Watkinson will be on the edge of his seat at the Olympic Stadium. "I'm going with my wife," he says. "She said, 'I know if he wins you're going to blub, aren't you?' I said she's probably right, but I won't be the only one."

Additional reporting by James Sharpe

A life in brief

Born Mohamed Farah, 23 March 1983, Mogadishu, Somalia.

Family His father is from London and his mother lives in Somalia. Came to live with his father in London when he was eight. Married childhood friend Tania Nell in 2010; they are expecting twins.

Education Feltham Community College in West London, and St Mary's University College in Twickenham.

Career He excelled as a school cross-country runner and soon became Britain's top distance runner. After failing to qualify for the 5,000m final at the 2008 Olympics, he became world champion in the 5,000m in South Korea in 2011, also winning silver in the 10,000m.

He says "I don't just want to be British number one; I want to be up there with the best."

They say "Mo has always been a good runner, but he became a great runner when he decided finishing in the top 10 in the world was not good enough." Steve Cram

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments