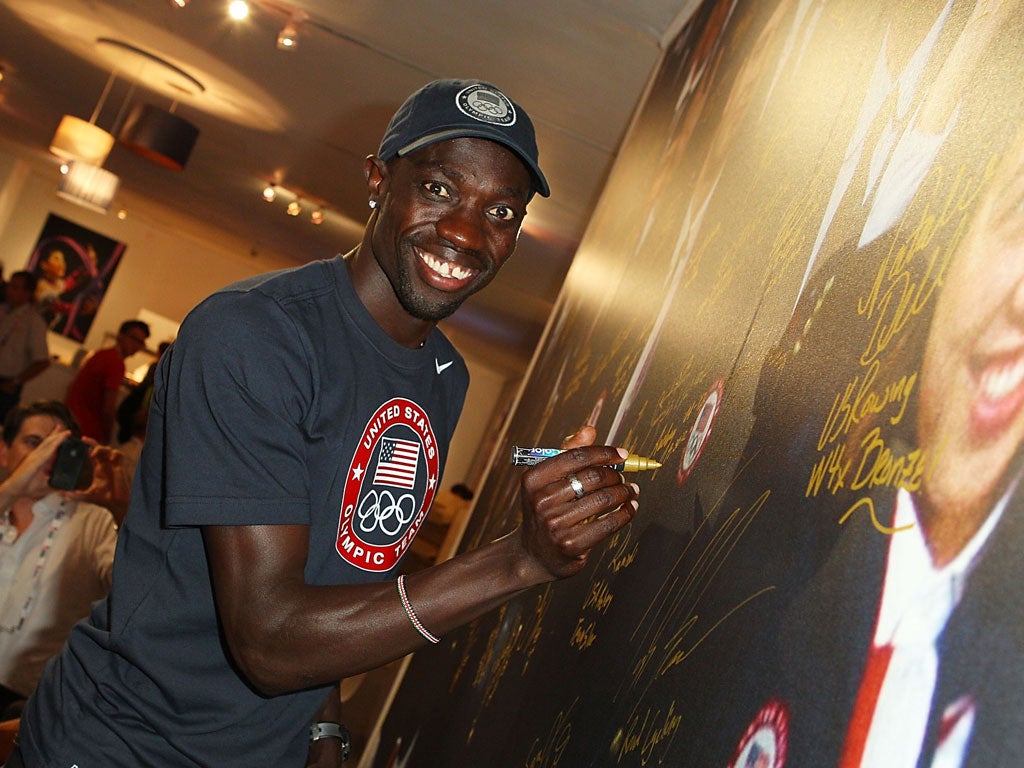

Lopez Lomong: The 5,000m finalist who's running scared

Abducted at six by Sudanese rebels, Lopez Lomong escaped and ran for his life. Tonight he lines up in the final

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Blink and you might miss him tonight, when he is introduced to the Olympic Stadium as just another athlete, and then when he tucks in among a field of 15 in the 5,000m final, in the all-American red. But the very act of running fast and long for a finishing line carries a resonance for Lopez Lomong which makes going for gold a comparatively trifling thing.

To the uninitiated who are looking only for Britain's Mo Farah in the field, this race will seem a fair stretch – 12 and a half laps of the track – but Lomong has a different perspective on distance. It is 21 years since he found himself locked into an ordeal which demanded that he run for his life, for three days and three nights, branches slapping at his legs and thorns tearing at his skin, through the scrub of the land that is now Southern Sudan and out towards the Kenyan border.

That he should have made it provides the last weekend of competition with a story of Olympian spirit and also grants a torchbearer to the north-east African nation he has left behind.

Lomong was six and settled in at the Sunday morning Mass he was attending as always with his family in the southern Sudanese village of Kimotong, when he heard the rumbling trucks of what he now knows were the Sudanese rebel People's Liberation Army. While the congregation attempted to take cover, he was abducted from their midst by men wearing what he now knows were chains of bullets and marched out into the brilliant sunshine.

Thus Lomong became one of the 20,000 so-called "lost boys" of the Nuer and Dinka ethnic groups who were either abducted or orphaned during the 22-year second Sudanese civil war. When weeks turned to months with no word of him, his family assumed him to be dead, and buried him in absentia. He was actually living in the midst of death at a recruiting prison camp hours away, where boys whom he knew one day would not be there the next. Some could not be roused when the day's single meal-time arrived. "They were dead," he says. "I'd never seen a dead boy before."

The means of escape from the prison – a hole in a chain-link fence – was as miraculous as its accomplishment. None of the small group of boys who crawled through that hole had shoes. Rocks cut at Lomong's feet and he was not the fastest. "I couldn't keep up with the others at times," he says. "My friends lifted me. They carried me."

A deliverance, of sorts, came on the fourth searing day, with the sight of a United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) truck. He quickly found himself in Kakuma, the refugee camp on the Kenyan border that would become home for the next decade, Lomong sharing a hut with 10 boys and finding his only escape in football. The camp circuit was 18 miles in total. "I ran and ran to play football," he says.

It was in 2000 that he was adopted, as part of a Catholic Charities' resettlement programme, by a family in Tully, a small town in upstate New York, where he went to high school and first started to think that running could be a career, rather than a way to stay alive. He became a United States citizen in July 2007 and made the national Olympics team a year later, taking part in the 1500m race in the 2008 Games. It was there, as a college graduate from Northern Arizona University and the US flag bearer, that he bore the trappings of one who had crossed a chasm. There was sponsorship by Nike and photographs with President George W Bush.

Lomong, now 27, is not the only one who has made this journey. There is also Britain's own Luol Deng, captain of the GB basketball team – and of the Chicago Bulls – whose family settled in Brixton after escaping the second South Sudanese war. Deng's story was recently encapsulated by Team GB basketball coach Chris Finch, a Texan. "What have we got here?" he asks. "A big-hearted nation takes in a struggling Sudanese family and gives them a life. Luol repays that nation by undertaking a mission impossible against overwhelming odds. He has never wavered and I hope you guys are proud of him because you bloody well should be…"

But Lomong's latest mission is certainly not impossible and it is the one which animates him today. If he is honest, he will say he is a little bit tired of the all-American heroism thing. He is a more natural 1500m runner and relatively inexperienced at tonight's distance. But he qualified as the fourth-placed finisher in Wednesday's first heat, one place behind Farah, the new 10,000m champion, having set this year's world-best time of 13min 11.63sec in his first-ever race across this distance. He is a contender.

He is looking beyond the finishing tape, too, having spoken this week in the hope of drawing attention to 4 South Sudan, the partnership he has helped establish between the international children's charity World Vision and the Lopez Lomong Foundation. "We need to be able to go back and give these people education, clean water, nutrition, medicine," says Lomong, who was reunited with his Sudanese family in 2007. It is thought there are more than 660,000 people displaced by fighting between Sudan and its neighbour, South Sudan. Malaria and diarrhoea are rampant in the overcrowded refugee camps a year after South Sudanese independence. Lomong has made it, but many more are still running.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments