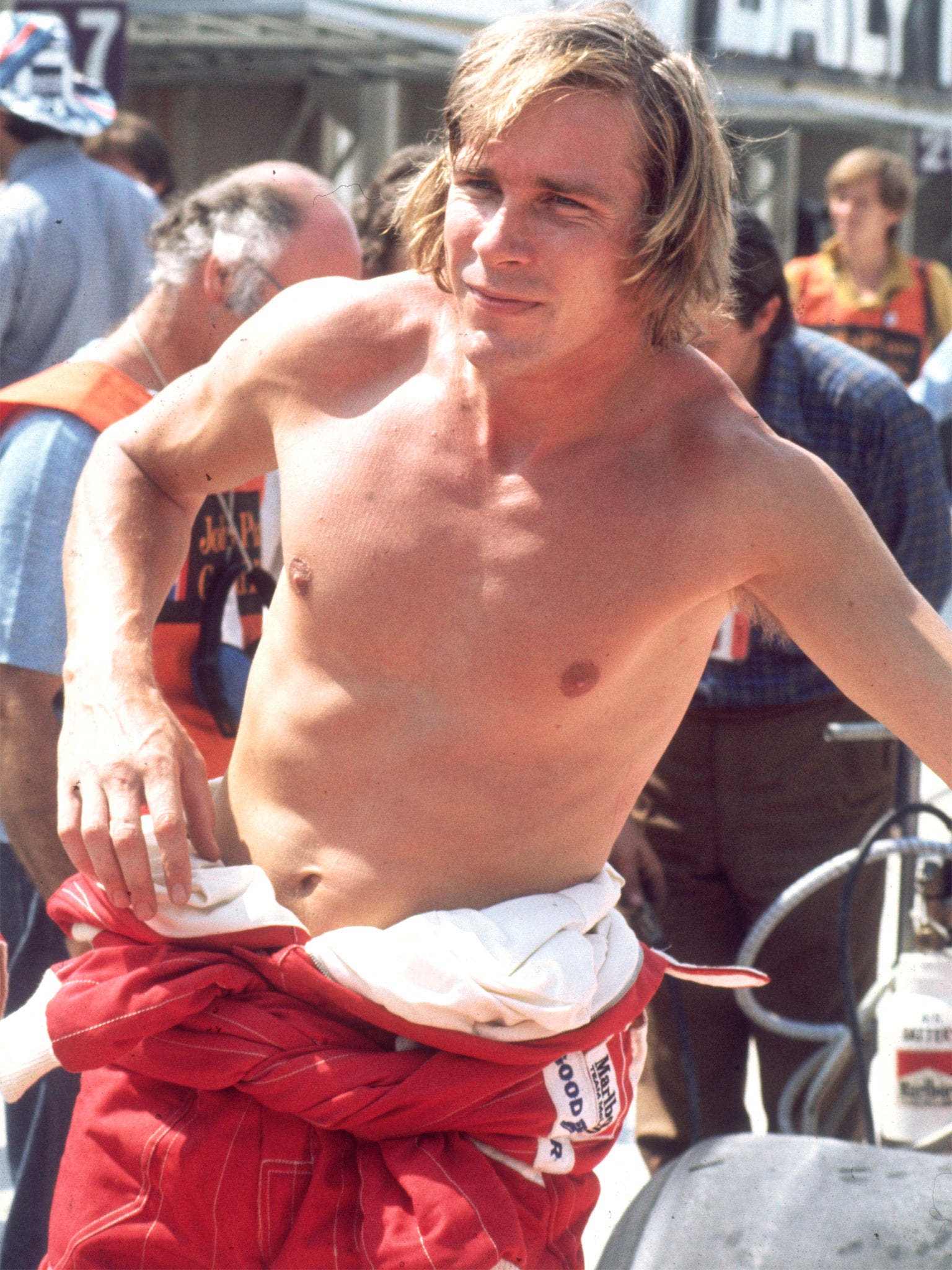

James Lawton: The James Hunt I knew is the subject of a new F1 movie

British driver was fascinating man whose epic duel with Niki Lauda in 1976 was typical of an era of glamour and glory – but also the ever-present threat of death

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amid all the hype building around the Hollywood blockbuster that will shortly bring back to life the extraordinary duel between James Hunt and Niki Lauda in 1976 there is a curiously poignant memory. It is of Hunt sitting in his elegant house beside Wimbledon Common, shortly before he died in 1993 at the age of just 45, and enthusing over his latest project.

The great dramas of his life were over. It was nearly 20 years since his tumultuous hand-to-hand battle with Lauda, who had returned with scarcely believable courage from his horrendous accident at the old Nürburgring – and the visit of a priest bearing the last rites – ended in a one-point victory in the rains of Mount Fuji.

The days of drugs and fine wine and serial romancing – 5,000 women were said to have submitted to his boyish charm – were in abeyance.

So what Hunt wanted to talk about, in some considerable passing, was a surefire commercial initiative. He had a plan to market a salad that would be enhanced by immersion in a microwave.

It will be interesting to see if director Ron Howard, who won a clutch of Oscars for his depiction of the life of Nobel Laureate John Nash in the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind, has the running time to squeeze in such oddities in the nature of a man and his times which, when you are jogged into looking back, tend to make today's Formula One resemble a hugely rewarded Advanced Driving School.

Certainly that epoch, during which today's Formula One chief Bernie Ecclestone offered the thought that the routine deaths of leading drivers was nothing so much as inevitable "culling", seems utterly proofed against excessive dramatisation by the gifted filmmaker, who was inspired by the recent superb documentary Senna.

Before Hunt won the French Grand Prix at the Paul Ricard circuit near Marseilles on his way to his world title he confided, "Sometimes I wake up with a gnawing feeling in the pit of my stomach. I think of all the friends who have died on the track and I wonder if I will be the next. I thought this morning, 'Wouldn't it be lovely to be a professional golfer: A nice walk in the sunshine, 18 good holes and then a little time at the 19th."

When he came home the winner, the adrenalin still pouring, he was a little breezier when discussing the fact that on the last lap he had thrown up. Was it the growing tension of his battle with the great Austrian? Was it more of those demons that came to him in the night? "Maybe it was a little bit too much champers and foie gras," he said. But you didn't have to look too hard into his eyes to suspect a somewhat different story.

The new movie, which is out in September, is called Rush – the one which came to the great racers when they put aside their fears at that time before Sir Jackie Stewart, appalled by the never-ending toll on his comrades, spearheaded the drive for greater safety.

However, judging by fleeting evidence from the film's trailer there is reason to believe that the complexities of such emotion will not be lost entirely in all the available dramatic material. Lauda, who astonishingly missed just two races after being dragged from his burning car by fellow drivers and raced to the hospital where he hovered between life and death for several days, is heard saying, "Why do we do this? Why do we do something that is killing so many?"

They did it of course because of that rush, the extraordinary combination of a glamorous life and the old Ernest Hemingway conviction that "the nearer you come to death the more alive you feel".

It was a theory not so easy to dispute on the sun-splashed morning after Hunt's triumph in France – at least not when you accompanied three drivers, Ronnie Peterson, the charging "Super Swede", Brazilian Carlos Pace and the Frenchman Patrick Depailler, on the little ferry from their hotel island of Bendor across the short stretch of sea to the mainland resort of Bandol.

They were bronzed and carefree, it seemed. They had beautiful companions and the drama of their lives stretched on to the next leg of the race between Hunt and Lauda, at Brands Hatch. There, Hunt would be disqualified – and within four years all of the ferry riders would be dead.

Pace died in a light aircraft crash, a few days after his Formula One rival Tom Pryce lost his life in the South African Grand Prix. Peterson was dragged from his car by Hunt at Monza in 1978 but died later in hospital in Milan, partly, it was alleged through medical negligence. Depailler was fatally injured in a private testing session at Hockenheim, the oldest of the trio to lose his life. He was 35.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments