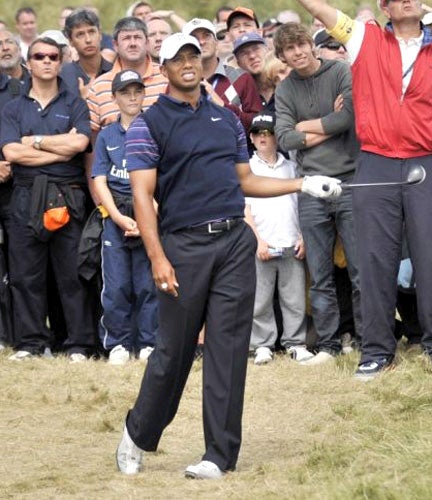

James Lawton: Woods has a bad day – but his recovery is rarely far away

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even when everything goes wrong for Tiger Woods, as it pretty much did yesterday, you know he will avoid the affliction of the poor souls who have laboured so long in his shadow. He will not stop believing in himself. He will not see a threat or a problem that cannot be resolved from within his own nature and talent.

It is not the doctrine of infallibility – no one who fired as many loose shots as he did while Tom Watson, 26 years his senior, showed precisely how you master this celebrated but virtually defenceless course, could begin to flirt with such a concept.

However, if Tiger accepts he can do wrong he also believes that every time he does and loses, which is the likelihood that grew maybe inexorably as he returned to the clubhouse six shots behind the 59-year-old who won the second of his five Open titles here in 1977, it is simply because he was just a little too slow to find the remedy for a passing problem.

On the way to his first-round, one-over-par 71, as Watson was combining a near faultless exhibition of course management with an extremely amiable impersonation of Jack Lemmon, Woods became increasingly exasperated by his failure to exert anything like control either over himself or the rest of the field. When he pulled his tee shot at the third into the scaffold of a television tower he yelled "Goddamit" and tossed his club aside.

At the 16th he was equally inflamed when he aimed for a safe place on the left side of the pin, completely misplaced his shot and left it plunging into the Wee Burn at the foot of the steeply sloping green. Then, when he played his third shot from the top of the opposite bank, you had still another reminder of why Tiger might believe he has never had a problem truly beyond the scale of his talent.

It was a chip shot of almost supernatural control, stopping dead just a few feet beyond the flag. Lee Westwood, who with the 17-year-old Japanese prodigy Ryo Ishikawa, always had an edge on his illustrious playing partner, was happy enough to take a double-bogey in an identical crisis at the same hole.

Even after Woods squandered chances of an eagle and birdie at the 17th and 18th and growled, "What's wrong with you, Tiger?" he made it clear that the solution lay just around the corner on the driving range.

"Yes, I made a few mistakes today," he said, "but hopefully tomorrow I can play a little better, clean it up and hit it, get myself heading in the right direction. I'll go on the range and work on it for a little bit, and then I can hit it a little better this afternoon and get ready for tomorrow."

It was in the end just a little matter of patience. Watson could recreate more than a hint of the old glory that invaded this beautiful course on the banks of the Firth of Clyde when he beat Jack Nicklaus in one of the most spectacular final rounds in the history of major tournament golf, he could move from one birdie opportunity to another with the easiest precision, but the toll of the years would wear him down soon enough.

Other veteran Open champions like Mark Calcavecchia and Mark O'Meara might make a better job of mastering conditions but just for a day or two, you sensed Woods was saying, and then Tiger would move into his place at the head of affairs.

He would get it right. In another man this might be dismissed as delusional. In Tiger it is an article of faith which explains why most accept that he is the greatest golfer who ever lived.

There were no mysteries, no blazing concerns, after the brief suspension of this belief. "Well, I certainly made a few mistakes today," he said. "Realistically, I should have shot one-under or two-under. I hit a couple of shots to the right and three-ripped from 15 feet and I didn't take advantage at the 17th.

"I was hitting irons out there today [he picked the driver just three times] because the wind was down. Most of the holes I would normally be hitting three-wood. No wind, so the two-iron goes to the same spot. We were just playing to the same areas, whether it's two-iron, three-iron, or whatever – we're just playing how we think the golf course should be attacked. You look among the guys who are playing well out there and you see a lot of the older guys, and three former Open champions in Tom, and the two Marks, Calca and O'Meara. They obviously understand how to play the course. They don't try to overwhelm it."

Three years ago Tiger adopted a similar policy in Hoylake, winning his third Open while using the driver just once over four rounds. Yesterday he never began to produce such a winning rhythm. When his body language wasn't mean it was despairing. "Yes, I got frustrated. I wasn't playing well, he admitted. "But the misses I had were the same shots I was hitting on the range so I need to go work on that and get it squared for tomorrow."

At two under and one under, Woods' playing partners Westwood and Ishakawa could both claim to have produced the superior course management. Mostly they hit their shots more sweetly than Tiger and their moments of frustration were concealed rather better.

Westwood said: "I would probably have taken a 68 at the start of the day, and I'm pretty pleased with how I handled the course." Ishikawa, known as the Bashful Prince in his homeland, was suitably modest, saying he was nervous to play with the Tiger and optimistic about beating the cut.

For the Tiger there was only the old imperative. It was to go away and work and reinvent himself and come back and destroy anyone with the temerity to stand in his way. Muhammad Ali once declared that a sparring partner had dreamt he had beaten him – and promptly apologised.

Here such an apology may not be required. But then maybe we should wait a little while. Tiger, after all, has a day or two more to get things right, and it would not be the first time that he made his world of golf stand still.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments