Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

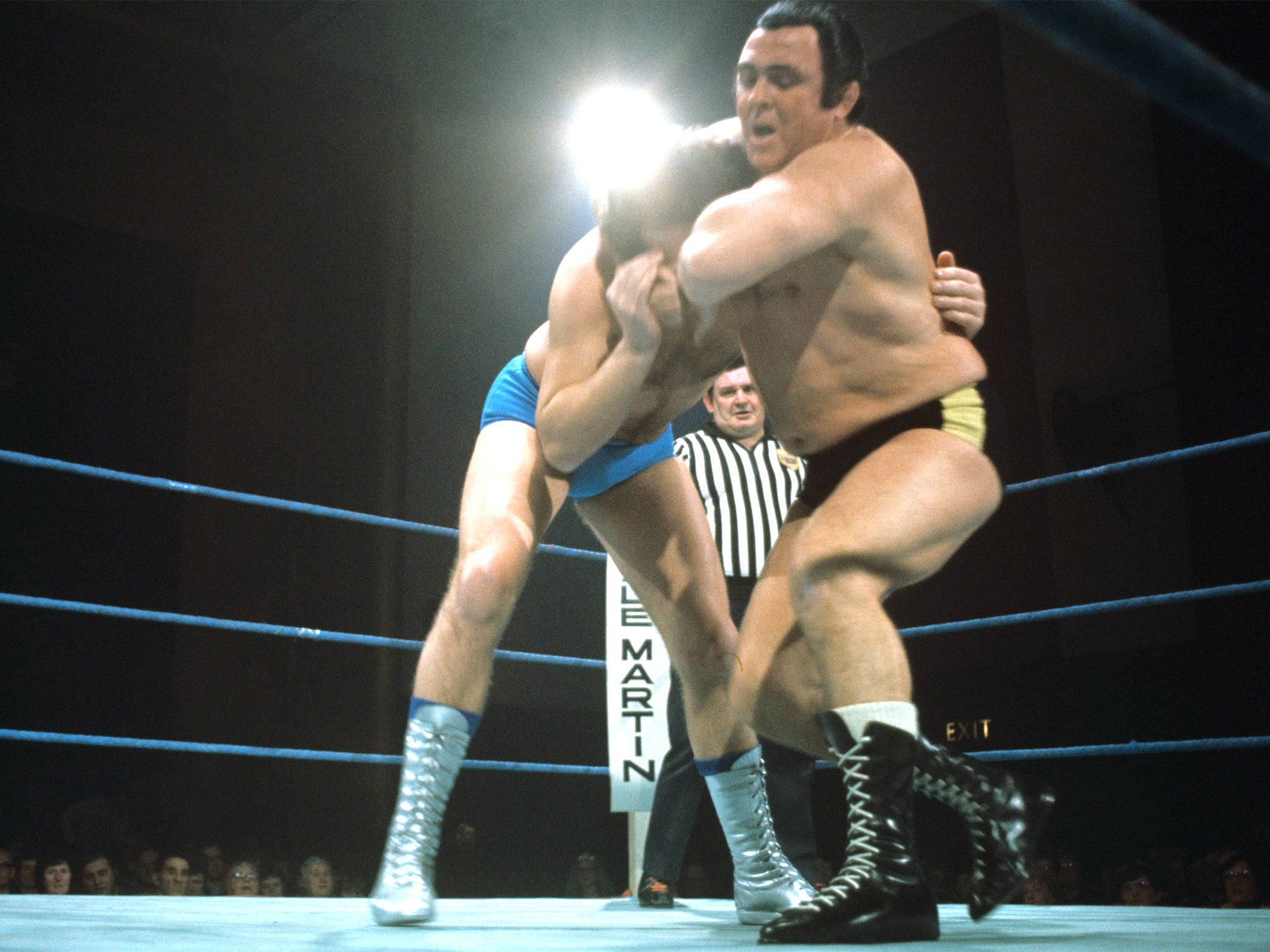

Your support makes all the difference.Long before the advent of Mike Tyson as "the baddest man on the planet", Mick McManus revelled in that role. Back in the Sixties and Seventies, the wrestler with the close-cropped coiffeur that looked as if it was a rug coated in Cherry Blossom's shiniest black was one of the most familiar, if reviled, figures on Britain's TV screens.

Watched by millions on ITV's Saturday-afternoon World of Sport, McManus, who died a week ago aged 93, was the ultimate anti-hero, the cunning, snivelling cheat whose dastardly disregard for the rules, such as they were, was compulsive viewing for some 20 years.

As he left the ring, inevitably triumphant, to a chorus of hisses and boos, outraged grannies battered him with handbags, even stuck hatpins into his black-trunked backside. They refused to believe the wrestling wasn't real, and McManus himself resolutely insisted, publicly at least, that it wasn't faked. But of course it was. Unlike his hair.

I know this from having spent some time on the road with McManus and a troupe of fellow grapplers during his heyday, given access to the dressing room and listening in on the muttered conversations between opponents – and sometimes the referee – as they discussed moves and falls that would most please the punters and promoters. When they went into the ring they always knew who would win – and how.

It was often a case of "You win in Plymouth and I'll win in Bradford" as the grunt-and-groan road show filled the provincial halls. Apart from the talk of tactics there wasn't much social chit-chat between the combatants. They all knew the ropes, and I gathered that many of the moves had been choreographed by McManus and rehearsed in a London gymnasium.

The squat, 5ft 6in McManus was the fixer, as well as the star turn. He acted as matchmaker for the principal promoters, the Dale Martin Organisation, which enabled him to say who won and where, in the process ensuring that he usually topped the bill himself.

During our time together it was clear that he was wrestling's ringmaster. He always travelled separately, attempting to get back to his south London home from wherever he was. He had his own driver, a fellow wrestler who usually performed in the show's curtain-raiser.

I got to know McManus well, and enjoyed the company of other wrestling notables of that era, among them "Laughing Boy" Les Kellett, a toothless Yorkshire grandfather well into his 60s who lurched around the ring like a drunk when on the point of defeat before unleashing his trademark forearm smash.

It was Kellett who demonstrated to me how such a potentially damaging assault was "pulled" a fraction from the recipient's face, and how capsules of cochineal or pig's blood were sometimes secreted in the ear or mouth and then burst to give the baying audience an appreciated touch of gore.

He and McManus had an alleged feud for years, as McManus genuinely did with his greatest rival, Jackie Pallo, with whom he refused to speak after Pallo revealed in his biography how most bouts were rigged.

McManus, the headmaster of contrived nastiness, was a remarkably quiet, polite and gentle individual outside the ropes. He once invited me to tea at his Dulwich home with his wife, Barbara, where the small hands that were professionally employed throttling throats lovingly caressed his collection of antique porcelain, a subject on which he was an authority.

Showbusiness with fake blood wrestling may have been, but sometimes the participants did get seriously hurt. There have been broken necks and limbs, and one instance of a wrestler left paralysed for life after crashing into a ring post when his opponent mistimed a head-drop.

"You should see some of the injuries I've had," McManus told me. "Sometimes it is impossible to get out of bed the next day because you have been battered so badly."

Since his trade was pure theatre, it seems appropriate that he passed away peacefully in a home for retired actors.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments