James Lawton: Age concern as Hopkins and Calzaghe Snr exchange jibes

He may be 43, but Bernard Hopkins roars defiance after ageist taunts from the Calzaghe camp

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

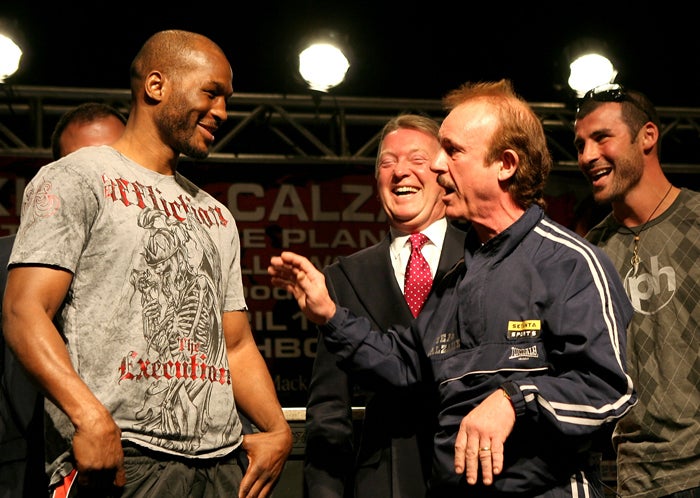

Your support makes all the difference.Maybe he made the point as much for himself, and some ebbing belief in the buoyancy of his status as boxing's most endangered time traveller, as for Joe Calzaghe. But Bernard Hopkins, aged 43, conjured the most jarring riposte when his opponent's father and trainer, Enzo, this week presented him with an old man's walking stick.

Take a closer at the Italian Dragon prior to this weekend's fight

Hopkins said that no one should forget November 1994, and what happened just a few blocks down Las Vegas Boulevard. They shouldn't forget the punch that sent disbelief into every corner of a sport long conditioned to the sometimes brutal force of the unexpected. Nor the words of television commentator Jim Lampley.

For the most obvious reasons, said Hopkins, they have been for him a source of special inspiration in these final days of the build-up to tomorrow's fight with a Calzaghe who is in a different league in speed and style, unbeaten in 18 years of fighting as an amateur and a pro, a world champion for 11 years and, at 36, seven years his junior.

The words of Lampley: "It's happened, it's happened... the old man has come through."

The old man: George Foreman, aged 45, and the new holder of two world heavyweight titles.

Twenty years after losing the title to Muhammad Ali in Zaire in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history, Foreman had beaten Michael Moorer, aged 27, for the WBA and IBF titles he had taken from Evander Holyfield.

Foreman, who found God and became the Punchin' Preacher in all the time he had to reflect on the African debacle, rushed back to his corner, knelt and prayed. He was dressed in the baggy red shorts he wore against Ali – and the aura of a man who had beaten time, the fight game's most ungovernable opponent. The big question here is whether Hopkins can walk in the steps of Foreman on Saturday night. It is one that surely gnaws, at least a little, at the heart of Calzaghe. It is the trouble with precedents if you are on the wrong side of them.

It doesn't matter that Moorer made a decision of historic stupidity, after outpointing the old man for 10 rounds, when he stood still, for the first time, in the path of a short and devastating right hand from Foreman that connected with the tip of his jaw. There was never any question that Moorer would fail to beat the count. Stunned, broken, he would have to live for ever with the fact that he had fallen for arguably boxing's ultimate sucker punch, and that it had come from out of an ancient mist.

All in all, it probably wasn't Calzaghe snr's smartest move to present the walking stick. It enabled Hopkins, while giving an impersonation of a sad old geezer, to point out gleefully that one of his more recent, and much favoured opponents, Antonio Tarver, had gone even further with the present of a wheelchair. And he was beaten hollow.

None of this disturbs the truth that there are few greater follies than staying in the ring too long and risking that moment when everything turns off at pretty much the same time, when the lights go out and the blood turns cold and the potential long-term damage is the incalculable one of living the rest of your life with no more vim than a zombie's.

This can be corroborated, apparently, by anyone who has recently seen Ali operating, according to the best medical opinion, within prison walls created not just by Parkinson's syndrome but the accumulated damage of a career that went on too long and required him to take far too much gratuitous punishment For anyone making cases studies of the problem there is no pressing need to leave this town and some of the more troubling aspects of its fight history.

Ali is perhaps the most compelling starting and finishing point. In 1980, at the age of 38, he persuaded many boxing people who should have known better than he had a ghost of a chance against his former sparring partner, the relentless and hugely underrated hitter Larry Holmes. Three years after sustaining so much damage from Earnie Shavers at Madison Square Garden – his senior medical adviser quit on the spot – Ali managed to do this by the reckless use of diuretics, which had a cosmetic effect but sent him into the ring no more than a shell of some recreated physical beauty. Watching him being beaten so remorselessly, in a converted parking lot at Ceasars Palace, made some notably unsentimental men cry.

Yet it is not so easy to place Hopkins in this forlorn category. His body is the product of a lifestyle regime which has been growing in dedication, some would say fanaticism, ever since he was released from prison in his early twenties. The other day, for example, he lectured his highly respected conditioning coach Mackie Shilstone on the harmful effects of consuming too much pomegranate.

Shilstone said, dryly, "Bernard, don't I get paid for telling you stuff like that?"

Another member of the fighter's corner, strategist Nazim Richardson, talks endlessly of Hopkins's survival instincts developed by the strength required to survive the prison experience. He says that in terms of knowing and dealing with the tough side of life, Hopkins and Calzaghe inhabit different planets. "Bernard has figured it all out," says Richardson.

Philadelphia's mayor, John F Street, recently acknowledged Hopkins's journey from the unpromising streets of the north end of the city by appointing him to his drug and alcohol commission. Said Street, "Bernard Hopkins is so much more than a superb fighter. He's a man who overcame a troubled youth, who believed in himself and reached the pinnacle of his profession. As a former inmate, Bernard knows first hand the struggle facing people as they leave prison and re-enter society. They face rejection and lose hope."

Naturally, Hopkins, survivor and prospective political opportunist, was happy to endorse such an opinion on a civic occasion of some pomp, saying, "I got out of the hard part of the city and I'm dedicated to helping others do the same. The oath of the street is a fool's oath."

Some would say, though, it is no more foolish than fighting on beyond your time, inviting the kind of denouement that can carry you straight to a high dependency ward. Yet Hopkins's dangerous justifications, some might argue, stretch beyond the old man's glory of Foreman.

Twelve years ago for example, some of us, not many it is true, persuaded ourselves that Holyfield had a fighting chance of beating Mike Tyson here. This was despite the fact that a few months earlier he had looked awful against Bobby Czyz, a puffed-up cruiserweight, and that he sounded as though he was already beginning to slur his words.

The instinct that he would win had much to do with his warrior nature and that Tyson, though four years his junior, had been gorging fat on boxing scraps ever since emerging from prison in Indianapolis. Yet the experienced trainer Teddy Atlas was just one extremely discouraging witness. He said, "OK, Evander is only 34 – but that's on the book and not in reality. He is at least 10 years older in the punishment he has taken, the wars he has fought. The Holyfield you are talking about, the great warrior, no longer exists." But he did. He backed up and beat Tyson gloriously and when the New York Athletic Commission banned him from boxing just two years ago it was not because of failed medical tests – he passed a battery of them – but "diminished skills". The most recent evidence of victories over Tarver and Winky Wright do not leave Hopkins open to such a charge, though of course one of the problems of fighting too long is that you never quite know when the curtains are going to come down.

Hopkins says, "People were calling me old 10 years ago, but they want you to think you are old. So, yeah, you can get little cramps here and soreness there, because you just happen to be human. You start second-guessing yourself and in a split-second of hesitation you can become old, you can be vulnerable. But you know I'm a strong-minded man. It comes from my past that wasn't always good and moulded me into something Joe Calzaghe can never be – and it doesn't make him a bad person either. But at times like this, at events like this, it does separate him from who I am, and this is something that gets played out in every fight I fight.

"I don't want to look like no jailhouse bully, looking for prey coming through the gates for the first time – so Joe, don't make me look like that jailhouse bully."

It is the least of Joe Calzaghe's ambitions. Joe simply wants to make Bernard look old and uncommonly reckless to be still in the ring. He has more than enough talent to do this but then as Hopkins mentioned with what some might say was close to psychological genius, Michael Moorer also fancied his chances against George Foreman.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments