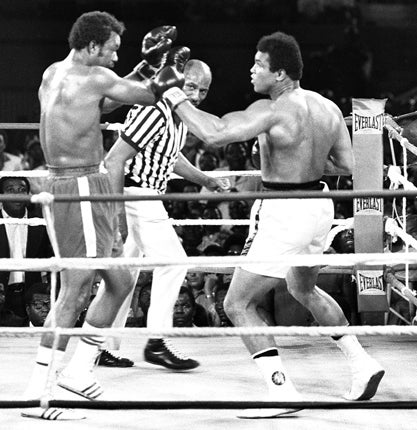

Great Sporting Moments: Muhammad Ali v George Foreman, World Heavyweight title fight, Kinshasa, Zaire, 30 October, 1974

One was a huge and apparently invincible ogre. The other was past his best, with question-marks over his stamina – and, some said, over his ability to survive the beating that awaited him. No one could have imagined what really lay in store, when Foreman faced Ali in Zaire. Ken Jones was there.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was early in the afternoon, not yet eight hours since Muhammad Ali had won, and he had probably not slept half that time. The tumult detonated by his defeat of George Foreman had briefly subsided and he lay back on the cushions of an easy chair in his villa alongside the swollen Zaire River.

He was dressed in a short-sleeved black shirt with matching slacks and had kicked off the heavy running boots that were his regular footwear in camp. Apart from a slight bruise beneath his right eye and some flecks of blood surrounding the iris, he was unmarked.

Later, he would rant from one press conference to the next. But at lunch-time, with myself, one other journalist and his household staff as the only witnesses, he rambled on for more than an hour through a generally subdued monologue that left out little of what he felt about the fight and its implications.

"Muhammad Ali stops George Foreman," he muttered with his eyes closed. "I kicked a lot of asses – not only George's. All those writers who said I was washed up, all those people who thought I had nothin' left to offer but my mouth, all them that been against me from the start and waitin' for me to get the biggest beatin' of all times. They thought big bad George Foreman, the baddest man alive, could do it for them, but they know better now."

As he started the next sentence, Ali remembered the presence of his aunt, Coretta Clay, and the other cook, Lanna Shabazz. He checked himself, then shaped rather than spoke the words. "Ah done fucked up a lot of minds."

Indeed he had, defying both logic and the widespread fear that Foreman would be too young and strong for him, and would inflict a terrible beating.

Nearly 35 years on, there remains a personal sense of the peril that appeared to exist for Ali as the contest drew closer. Had a six-week postponement, caused when Foreman suffered a cut by his right eye, interfered with the delicate psychological balance of Ali's preparation? Making some sense of it wasn't easy amid the shrillness that surrounded the challenger. Soaring from one fanciful proclamation to another, Ali was in splendid form; but bleak images were gathering in the minds of those who had established a function, real or illusory, at his side. Their raucous optimism carried little conviction, darkness bringing shudders of doubt, the realisation that their futures rested with the extent of Ali's will when exposed to Foreman's heavy artillery.

Night had fallen, and the broad sweep of the river passing close to where Ali was resting prior to making the 40-mile trip from N'Sele to Kinshasa emphasised a sense of deep foreboding. "George could hurt him badly," the novelist Budd Schulberg said. Schulberg was not alone with his fears. Foreman appeared invincible, a man of great strength whose punches arrived with the impact of a wrecking ball. It wasn't necessary to invent a nom de guerre for the brooding Texan who threw the heavyweight championship into disarray in Kingston, Jamaica on 22 January 1973, when he knocked out Joe Frazier after 95 seconds of the second round.

Larger men had fought in the division, but Foreman conveyed such an awesome impression of brute force when sending the previously unbeaten champion down six times (one pulverising right hurled Frazier so violently sideways that his feet left the canvas), that only a painfully demoralising experience could be imagined for anyone coming out of the opposite corner.

The day after Ali outpointed Frazier over 12 rounds at Madison Square Garden a year later, it was announced that Foreman would defend the title against Ken Norton in Caracas, Venezuela. Norton went in the second round, experiencing a small death from the moment Foreman entered the ring to fix him with a withering stare. He was a victim before the bell sounded, his eyes those of a terror-stricken hare, his legs trembling. "I hit a guy and it's like magic. You see him crumbling to the floor. It is a gift from God," Foreman said.

Foreman versus Ali was a natural progression – and one that would establish the one-time Cleveland numbers racketeer Don King as the major figure in boxing promotion. King at full blast, outbursts of strident hyperbole interspersed with detonations of manic laughter, employed his entrepreneurial gift to persuade all inhabitants of the planet that the coming together of Foreman and Ali was symbolic. "The prodigal sons will be returning to Africa," he declared. "This will be a spectacular such as has never been staged on Earth."

King had pulled together a consortium that included Risnelia Investment (a Panamanian group with links to the Zaire government), Hemdale Leisure Corporation (a British company formed by a south Londoner, John Daly, and the actor David Hemmings), Video Techniques Incorporated of New York, and Don King Productions. To ensure maximum television exposure in the United States, the fight was scheduled for 3am, with worldwide viewing figures predicted at more than one billion.

But what had been sold to President Mobutu of Zaire as a triumphant manifestation of his country's economic potential was soon in danger of collapse. The weeks prior to the fight had almost seen the sinking of the Don King flagship on the troubled waters of the fight game. First, his promised avalanche of tourists had not materialised. And a fortunate thing it was, too, since it turned out to be the rip-off of the decade. Monies were paid in the US, but no one in Kinshasa got the message, so that the promised and paid-for hotel rooms were not available. Lawsuits were flying.

With the fight only two hours away, no press credentials had been issued – our anxiety over this increasing with each minute spent crammed in a room at the Hotel Memling in Kinshasa until the problem was solved by a veteran New York publicist, Murray Goodman (but not before reporters of a nervous disposition had been driven to the brink of apoplexy).

Sport provides a convenient vehicle for exaggeration: success and failure, youth and ageing. When set against the ultimate verity, it is never thus. And yet the drama that unfolded in the Stadium of the Twentieth of May was almost suffocatingly intense. Even before the fighters reached the ring, I trembled in anticipation.

When the referee, Zack Clayton, called them together, Ali said (as we were later informed): "You have heard of me since you were young. You've been following me since you were a little boy. Now you must meet me, your master!" Foreman blinked and tapped Ali's glove.

Of course, as long as there was strength in his legs, Ali would dance, stick and move; taunt, parry, hold. He struck the first blow, a stiff right straight into the centre of Foreman's forehead. When Ali was driven back to the ropes and made no attempt to escape, the shrill instructions of his trainer, Angelo Dundee, could be heard across the ring: "Get away from there."

Somewhere in the middle of that opening session, Ali made a decision on how to shape the fight. "I fooled everybody," he would later tell us. "They thought I'd have to try and dance against George, that my legs would go and I'd get tagged. George thought so, too. But that was my main thing, not dancin'. The trick was to make him think he was the baddest man in the world and everybody had to run from him.

"Truth is, I could have killed myself dancin' against him. He's too big for me to keep moving around him. I was a bit winded after doing that in the first round, so I said to myself: 'Let me go to the ropes while I'm fresh, while I can handle him there without getting hurt. Let him burn himself out. Let him blast his ass off and pray he keeps throwin'. Let it be a matter of who hits who first, and that's me.' This was a real scientific fight, a real thinkin' fight. For me, it was. Everythin' I did had a purpose."

When Ali first took up station on the ropes halfway between his own and a neutral corner, an incredulous silence settled over the ringside. Foreman, at first puzzled, prowled forward and unleashed a wide hook to the body, and then another.

"Ali's going to get killed," somebody yelled in the row in front of me. Dundee led the imploring chorus from Ali's corner, anxiety loud on their lips. "Move, for Christ's sake move," Dundee screeched.

Taking a tremendous risk, Ali lay back over the ropes as Foreman closed with him again. Then a stinging combination of punches leaped into the champion's face. The pattern did not alter through rounds three and four, but in the fifth a

terrible left hook pounded into Ali's head, quickly followed by another. In withstanding those blows, Ali turned the contest. As though satisfied that he had at last drawn the ogre's strength, Ali took up the initiative with rasping jabs, and in the seventh a right almost sent Foreman through the ropes.

At the start of the eighth, Foreman hit Ali with three head punches before stumbling on to a counter. Sent sideways by a left hook, he went down from a following right. He struggled upright, but not in time to beat the count.

Pandemonium broke out. In the mad scramble to reach the dressing room, I offered a helping hand to Schulberg who had been knocked down in the surge. His eyes were filled with tears of joy.

We fought our way through the crowd, and I flopped down alongside Ali's ring doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, our backs against a wall. Ali lay on a rubbing table, naked but for a towel thrown across his loins. "Look," Pacheco said, pointing at members of Ali's entourage. "They've already taken all his stuff. His robe, his shorts, his boots, his gloves, even his socks. They'll sell it."

Then the rains came. The fight would not have survived a storm that turned the highway into a torrent, hammering on the roof of the vehicle that carried us back to N'sele, flood water steadily rising, the driver urged on by promises.

Despite being in the best condition he'd known since being forced out of boxing by the US government in 1967, Ali may have harboured doubts about his legs and stamina, but his decision to let Foreman crowd in on him had to be seen as an act of calculated bravery.

"I have been boxin' for 20 years and I'm a pretty good fighter," he said. "I can walk into the firin' line with a man like Foreman and I got no fear. Nothin' can happen that I don't understand. I been to school. When he got knocked down, it was new to him and he was lost."

In the villa, having eaten two large steaks and 12 scrambled eggs, the champion was watching a television cassette of a fight preview. "Watch this," he said. "I was right, wasn't I? I said I'd stop him after seven and he went in eight. I even cancelled the rain. It stayed dry for the fight, then an hour after it there was a storm that nearly flooded the place."

When Foreman's manager, Dick Sadler, appeared on the screen, he said his man was a murderous puncher. Next we saw Sadler holding the heavy bag and almost being hurled off his feet by the impact of Foreman's blows. "Trouble was," said Ali, as if they could hear him, "nobody was holdin' me."

A version of this article was originally published in October 2004

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments