Bidding a sporting farewell...

The great and the good of sport who passed away in 2009, Paul Newman salutes them all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The admirable Shep was always the players' choice

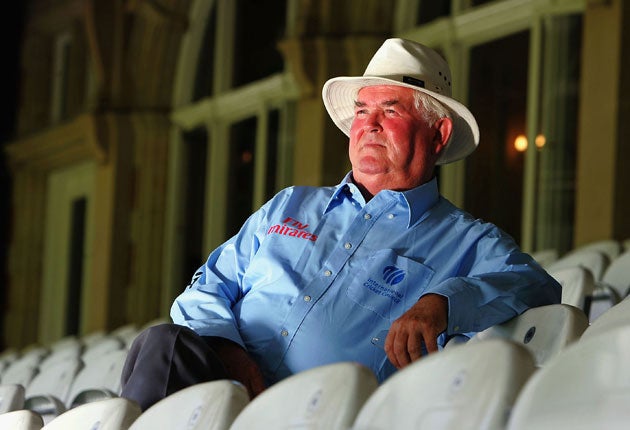

If Dickie Bird was England's best-known cricket umpire, few would disagree that David Shepherd was the most respected official within the world game. Players in particular loved "Shep".

His judgement was of the highest order, but players also appreciated the common sense and humane way in which he went about his work.

He was an umpire for 24 years and stood in 92 Test matches, 172 one-day internationals and three successive World Cup finals.

Born in Devon, Shepherd was a forceful middle-order batsman for Gloucestershire. He made a century on his debut and played at first-class level for 14 years before making his umpiring bow in 1981. He took charge of his first Test match, between England and Australia at Old Trafford, four years later.

Shepherd was on the International Cricket Council's first list of elite umpires and for many years was the game's outstanding official.

He contemplated retirement in 2001, mortified at missing three wicket-taking no-balls as Pakistan beat England at Old Trafford, but he was persuaded to carry on. His last Test was between the West Indies and Pakistan in Jamaica four years ago.

One quirk that always amused crowds was Shepherd's reaction whenever the score reached the dreaded "Nelson" figure of 111 (near the end of his life, Admiral Nelson was said to have had just one eye, one arm and one leg).

According to superstitious cricketers, the number brought bad luck. Players on the batting side are supposed to lift one leg off the ground until the score moves on; Shepherd, emphasising his neutrality, would lift one leg and then the other.

O'Brien put the bit between his teeth to rule the paddock

Vincent O'Brien was the greatest trainer of thoroughbreds in the 20th century and the man responsible more than any other for turning horseracing into the multi-million pound industry that it is today.

It would be hard to imagine anyone ever coming close to matching the Irishman's achievements on the Flat and in National Hunt racing.

O'Brien started out in the latter, winning four Cheltenham Gold Cups, three Champion Hurdles and three consecutive Grand Nationals, and went on to even greater glory on the Flat, in which he won six Derbies, three Arcs, 16 English Classics and 27 Irish Classics.

O'Brien was associated with some of the sport's most successful individuals, including Robert Sangster and John Magnier, his business partners, and Lester Piggott, his favourite jockey. He trained some of the most famous horses of the last 50 years, among them Nijinsky, The Minstrel, Roberto and Sir Ivor.

Recognising Northern Dancer's worth as a stallion from an early stage, O'Brien was a master at selecting yearlings and turning them into outstanding racehorses. His Ballydoyle stable, where he rarely kept more than 60 horses, became a byword for meticulous preparation. For example, he was the first trainer to install all-weather gallops.

O'Brien never left anything to chance. In 1977, fearing that The Minstrel might be upset by the noise of the Derby crowd, he told his assistant, John Gosden, to stuff cotton wool in the horse's ears in the Epsom parade ring. It worked a treat.

Wor Bobby, the embodiment of all that is good in football

He never won a league title in his home country and was hounded out of his job with the national team, but English football grew to love Sir Bobby Robson like no other manager. His passion for the sport never dimmed and his death brought an outpouring of affection for a man who came to represent all that was good in the English game.

As a player, Robson won 20 England caps. An attacking midfielder, he combined speed and strength with technical ability and tactical awareness. The latter served him well in a managerial career that took off with Ipswich and led to his taking charge of England.

Diego Maradona's infamous handball ended his first tilt at World Cup glory in 1986 but Robson was admirably restrained in his reaction to the quarter-final defeat. "It wasn't the hand of God, it was the hand of a rascal," he said.

Four years later, the manager had already been given a clear indication that his contract would not be renewed by the time England had reached the semi-finals of Italia 90. They lost on penalties to Germany in a flood of Paul Gascoigne's tears. "Not a day goes by when I do not think about the semi-final," Robson later reflected.

He went on to manage with great success in Holland, Portugal, Spain and, at last, at his beloved Newcastle United. Under Robson, Newcastle finished fourth, third and fifth in successive years in the Premier League, only for the club to sack him. For many years Robson fought cancer with the spirit he tackled adversity during his life. He died in July at 76.

And lest we forget...

Jack Kramer won Wimbledon in 1947 but, as a promoter, he played a major role in tennis going Open. Sidney Wood was the only man to win Wimbledon without having to show up for the final. The American's opponent in 1931, Frank Shields, withdrew with a knee injury. Henry Surtees, the 18-year-old son of John Surtees, the 1964 Formula One world champion, died after an accident in a Formula Two race at Brands Hatch. Darren Sutherland, 27, who won a boxing bronze medal for Ireland at the 2008 Olympics, was found hanged at his home in south London. Arturo Gatti, another exciting boxer, was found dead in a Brazilian hotel room. He was 37. Ingemar Johansson shocked boxing by knocking out Floyd Patterson to win the world heavyweight championship in 1959. Greg Page was born in the same town as Muhammad Ali, Louisville in Kentucky. He never fully recovered from an operation to remove a blood clot. Terry Lawless managed more than 50 boxers, including John H Stracey, Jim Watt, Charlie Magri and Frank Bruno. Reg Gutteridge was ITV's voice of boxing for more than 30 years. He was a flyweight before losing a leg in Normandy in 1944. David Vine was a BBC TV presenter who hosted snooker, 'A Question of Sport' and 'Ski Sunday'. "Mac" Henderson, a member of the Scotland team that won the Triple Crown in 1933, was the oldest Test player in history when he died at 101. John Holmes helped Britain win the rugby league World Cup in 1972. Leon Walker, a 21-year-old Wakefield Trinity player, died after a tackle in a reserve game. He had a heart defect. Jan Wilson, 19, and her fellow apprentice jockey Jamie Kyne, 18, died after a fire in Yorkshire. Paul Birch, who died of bone cancer at 46, was a midfielder for Aston Villa and Wolves. Mike Keen captained QPR to the 1967 League Cup, Alan A'Court made nearly 400 appearances for Liverpool, Hugh Kelly captained a Blackpool team who were second in the League in 1956, Ray Charnley was Blackpool's leading scorer for nine successive seasons, Alan Suddick was a midfielder with "as much ability as George Best", Alan Kelly was an Irish goalkeeper who made 512 appearances for Preston, and Albert Scanlon was a "Busby Babe" who recovered from a broken leg and fractured skull in the Munich air crash to resume his Manchester United career.

In passing

Bill Frindall Cricket scorer

"The Bearded Wonder", as the BBC's Brian Johnston called him, turned cricket scoring into an art form in more than 40 years on 'Test Match Special'. The former RAF corporal developed his own complex scoring charts which enabled him to recount in an instant what had happened during every ball. He covered more than 350 Test matches. Frindall was not the easiest man to get along with but quickly formed a strong bond with the commentator, John Arlott, who was said to have told him on his arrival in 1966: "I gather you like driving. That's good, because I like drinking. I think we're going to get on."

Robert Enke German goalkeeper

Although he did not make his international debut until he was 29, the 32-year-old goalkeeper was expected to be Germany's first choice at the 2010 World Cup. Born in Jena, he played with varying degrees of success for clubs in Germany, Portugal, Spain and Turkey before making his mark with Hannover 96. Having been kept out of the national team by former Arsenal keeper Jens Lehmann, Enke won his first Germany cap in March 2007. However, he was a troubled man and suffered from depression, particularly after the death of his two-year-old daughter. He committed suicide when he was struck by a train at a level crossing.

Chris Finnegan British boxer

Twelve years after the last British boxer won an Olympic gold medal, Finnegan surprised almost everyone with his middleweight triumph in Mexico in 1968. The bricklayer from Buckinghamshire had not even been expected to make the team, but he survived two standing counts in his semi-final and then outpointed Russia's Aleksey Kiselyov to win the title. A southpaw with good ring skills and a huge heart, Finnegan had a successful professional career, though he lost his only world-title fight. His younger brother, Kevin, also boxed. It was said that a daily pint or two of Guinness was an essential part of the Finnegan brothers' training regime.

Bleddyn Williams Welsh rugby player

The "Prince of Centres" was the outstanding rugby union player of his day. Williams was only 5ft 10in tall, but he was powerfully built, had a rare turn of speed and a lightness on his feet that saw him sidestep opponents with apparent ease.

After the Second World War, Williams joined Cardiff, for whom he scored 185 tries in 283 appearances. He also played 22 times for Wales and toured New Zealand and Australia with the British and Irish Lions. Williams turned down £6,000, which was an astronomical sum in those days, to play rugby league for Leeds on the grounds that the amateur game had been good to him.

Vic Crowe Welsh footballer

Although born in South Wales, Crowe grew up in Birmingham and enjoyed his best years in football there. Having spent 12 seasons as a player at Aston Villa, where he built a reputation as a fearless wing-half, Crowe returned as a coach in 1969 and was appointed manager the following year. The club were in the doldrums, but Crowe built the foundations for a revival that would blossom under his successor, Ron Saunders. Crowe played 16 times for Wales and captained his country for the first time in 1960. Amused team-mates pointed out that he was the only man in the dressing room without a Welsh accent.

Douglas Bunn British showjumper

Nobody had a greater influence on British showjumping in the post-war years than Bunn, who created the All England Jumping Course at his home at Hickstead in West Sussex. A former international showjumper, he was a visionary entrepreneur who brought sponsors and television into the sport. Bunn had several run-ins with riders, including his headline-making clash with Harvey Smith in 1971. The two men had argued before the Jumping Derby because Smith had forgotten to bring back the trophy he had won the previous year. When Smith won again, he cantered around the arena before turning to Bunn and delivering his famous V sign.

Betty Jameson Women's golfer

The Ladies Professional Golf Association owed much to Betty Jameson. The former newspaper reporter was one of 13 women, including Babe Didrikson Zaharias and Patty Berg, who founded the LPGA in 1950. Being a photogenic blonde, she ensured that the fledgling tour was given plenty of publicity. Jameson won the 1947 US Women's Open, where her 72-hole total of 295 was the first time a woman broke 300. A famously straight hitter, she once asked a playing partner to mark her ball on the green as she prepared to play from 175 yards away. "It was in my line," she explained later.

Kamila Skolimowska Hammer thrower

Kamila won the women's hammer throw gold medal at the Sydney Olympics but died after collapsing in training. She was 26.

Paul Newman

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments