Baseball: Fenway - more than just a park

The home of the Boston Red Sox, which is 100 years old tomorrow, defines American history like no other place

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.These might be the maunderings of an embittered Everton supporter who was in the crowd at last Saturday's FA Cup semi-final, but really, haven't things come to a pretty pass in English football when Liverpool play Everton at Wembley and the former's two principal owners aren't even there, citing a conflicting commitment to their first sporting love, the Boston Red Sox baseball team?

Still, in fairness to John W Henry and Tom Werner this is quite a season to be a Red Sox fan, let alone a Red Sox owner, for it marks the centenary of the team's venerable and atmospheric home, Fenway Park.

Tomorrow, it will be 100 years to the day since the purpose-built ballpark hosted its inaugural major league game, in which the Red Sox beat the New York Highlanders 7-6. It's unlikely that any of the 27,000 crowd gave it much thought at the time, especially with the sinking of the US-bound Titanic a few days earlier dominating most conversations, but an icon of Americana had been born, later becoming one of the 150 buildings chosen by the American Institute of Architects as having defined "The Shape of America". If anyone were ever to step out of a Norman Rockwell painting, it would probably be to go to Fenway Park.

Not for nothing did Henry and Werner call their company, the company that in 2010 bought Liverpool FC, the Fenway Sports Group.

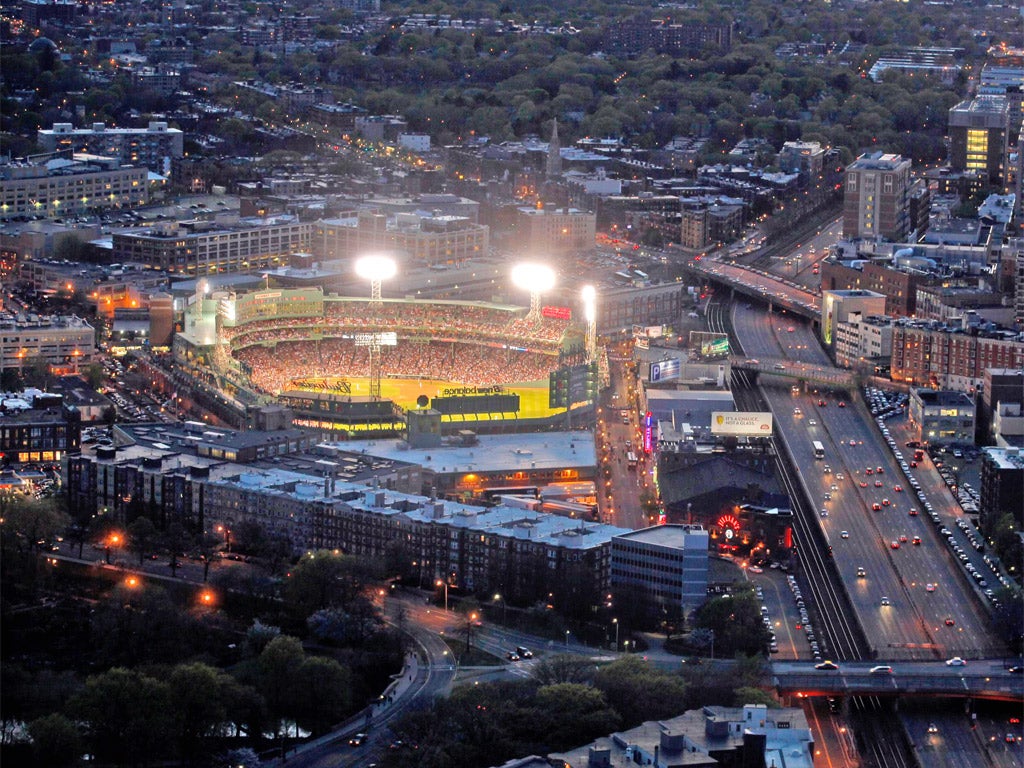

Today, Fenway Park is revered for its history and, in an era of edge-of-town super-stadia, its central Boston location, its smallness and quaint idiosyncrasies.

In April 1912, however, it represented modernity. Most American ballparks were still made of wood, and since many of them also were located close to railroads, destructive fires started by sparks from passing trains were regular occurrences. The new Red Sox home, by contrast, was built in brick and steel, the same components that seemed to have forged one of its earliest heroes, a moon-faced phenomenon called George Herman Ruth.

Boston fans loved Ruth, the man they called "Babe" but also "Bambino", and mourned when on 26 December 1919, at the age of 24, he was sold to the New York Yankees for $100,000 in cash, plus a $300,000 loan with Fenway Park offered as collateral. The mourning continued until 2004, when the Red Sox won their first World Series since 1918, a seemingly interminable drought ascribed throughout baseball to "the Curse of the Bambino".

Despite the 86-year failure to win a World Series, Fenway Park hosted many of baseball's epic moments and was graced by its greatest heroes, few greater than the slugging colossus Ted Williams, a southpaw like Ruth, whose .400 batting average in the 1941 season has never been surpassed or even matched.

In 1946, Williams struck what is still the mightiest home run in Fenway's 100-year history. It travelled more than 500ft, crashing through the straw hat of fan Joseph A Boucher, sitting in section 42, row 37, seat 21. A single red seat among the standard green seats now marks the spot, and outside the stadium, Williams is immortalised, 8ft high, in bronze.

As for Boucher, he later told The Boston Globe that the prodigious homer bounced off him and landed a dozen rows higher up. "But after it hit my head I was no longer interested," he added.

If Fenway Park had known only baseball, it would still be one of America's most cherished cultural shrines. But it has witnessed much besides, not least a 1919 rally, addressed by an impassioned Eamon de Valera and attended by 60,000 people, in favour of Irish independence. In 1920, boxing became part of the stadium's repertoire, and America's political heavyweights too have delivered knockout blows at Fenway Park. In 1944, President Franklin D Roosevelt delivered his final campaign speech there. Three days later he won an unprecedented fourth term. As for the likely protagonists in this year's presidential election, both have turned Fenway's unique aura to their advantage: the former Massachussetts governor Mitt Romney used it to host a barbecue for 800 campaign donors, and Barack Obama held a fundraiser there during his first run for the White House.

Nevertheless, it is baseball, and only baseball, with which Fenway Park is synonymous, even though it is in many ways unsuited to the modern game. "A compromise between Man's Euclidean determinations and Nature's beguiling irregularities," is how the novelist John Updike lyrically described it, for it is squeezed into an urban space that by any sensible measure is too small for it. More than any other ballpark, including the similarly evocative Wrigley Field, home of the Chicago Cubs, it is a place of quirks, none quirkier than the so-called Green Monster, a wall 240ft long and 37ft high that runs along the side of the abnormally short left-field, and was built to keep balls inside the stadium and non-paying spectators out. As Henry and Werner have perhaps reflected, the Green Monster is to Fenway what the Kop is to Anfield: part of the very soul of the place.

That soul has been threatened down the years. In 1965, the Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey declared his intention to tear down the "hopelessly outdated" ballpark and build a handsome new arena with a retractable roof.

Similar plans were still being mooted 35 years later, when the Red Sox general manager, Dan Duquette, told the Globe: "The longer we wait, the further behind we'll fall. We need a new ballpark to survive."

The parallels with Premier League football are striking, and in England, of course, Anfield is one of the grounds deemed, in its present form, to be commercially inadequate. Perhaps significantly, though, it was Henry and Werner, after their consortium bought the Red Sox in 2001, who rejected the scheme to demolish the old stadium and build a swankier look-alike, preferring a programme of sensitive refurbishment and renewal. "When you sit in your seats, you can almost imagine the ghost of Babe Ruth or Ted Williams," said Werner. "You don't create an imitation if you have the real thing."

It is unlikely that he and Henry feel quite as sentimental about the ghosts of Billy Liddell and Bob Paisley: why would they? Still, at least they will be attending the FA Cup final on 5 May – even though it clashes with the visit of the Baltimore Orioles, the Red Sox's nemesis last season, to their beloved Fenway Park.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments