Aryan ideals, not ancient Greece, were the inspiration behind flame tradition

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a two-word answer to those who think the Olympic torch is a symbol of harmony between nations that should be kept apart from politics – Adolf Hitler.

The ceremony played out on the streets of Paris yesterday did not originate in ancient Greece, nor even in the 19th century, when the Olympic movement was revived. The entire ritual, with its pagan overtones, was devised by a German named Dr Carl Diem, who ran the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

Although he was not a Nazi, and was appointed to run the Olympics before the Nazis came to power, Diem adapted very quickly to the new regime, and ended the war as a fanatical military commander exhorting teenage Germans to die like Spartans rather than accept defeat. Thousands did, but not Diem, who lived to be 80.

He sold to Josef Goebbels – in charge of media coverage of the Games – the idea that 3,422 young Aryan runners should carry burning torches along the 3,422km route from the Temple of Hera on Mount Olympus to the stadium in Berlin.

It was his idea that the flame should be lit under the supervision of a High Priestess, using mirrors to concentrate the sun's rays, and passed from torch to torch along the way, so that when it arrived in the Berlin stadium it would have a quasi-sacred purity.

The concept could hardly fail to appeal to the Nazis, who loved pagan mythology, and saw ancient Greece as an Aryan forerunner of the Third Reich. The ancient Greeks believed that fire was of divine origin, and kept perpetual flames burning in their temples.

In Olympia, where the ancient games were held, the flame burnt permanently on the altar of the goddess Hestia. In Athens, athletes used to run relay races carrying burning torches, in honour of certain gods.

But the ancient Games were proclaimed by messengers wearing olive crowns, a symbol of the sacred truce which guaranteed that athletes could travel to and from Olympus safely. There were no torch relays associated with the ancient Olympics until Hitler.

The route from Olympus to Berlin conveniently passed through Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria, and Czechoslovakia - countries where the Nazis wanted to extend their influence. Before long, all would be under German military occupation. In Hungary, the flame was serenaded by gypsy musicians who would later be rounded up and sent to death camps.

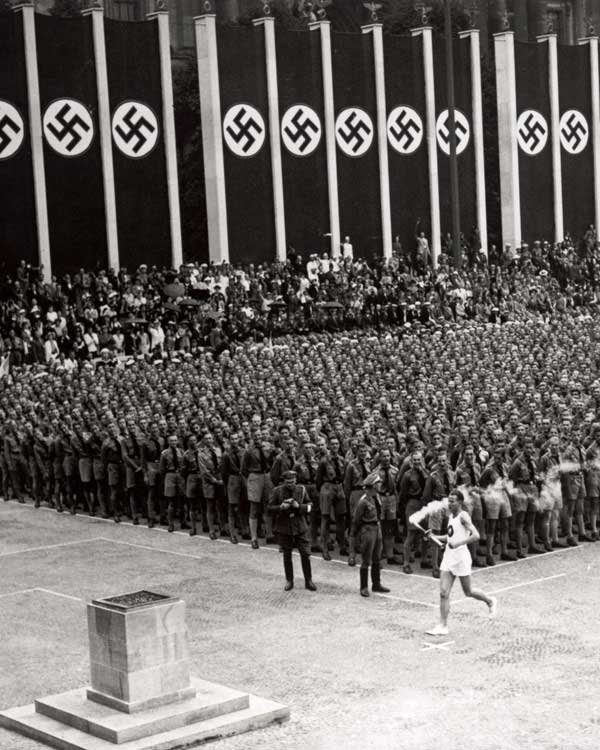

In Berlin, the flame was carried the last kilometre along Berlin's main boulevard, by a 26- year-old runner named Siegfried Eifrig, who was watched by hundreds of thousands as he transferred the flame to a cauldron on an altar surrounded by vast Nazi flags. Eifrig, amazingly, is still alive, aged 98, and told the BBC this month that carrying the ceremony should be a purely sporting affair.

Despite its dark political overtones, the event was an unqualified success for the organisers, immortalised in a propaganda film by the Nazi director Leni Riefenstahl. The ritual has been repeated before each Olympics but not always with such organisational flair.

In Melbourne, in 1956, the 19-year-old athlete Ron Clark burnt his hand as he put the torch to the cauldron, because technicians had increased the gas flow, fearing it might not light. When the Games returned to Australia 44 years later, Clark was persuaded to do the honours again, and burnt his forearm during a rehearsal. One of the Australians taking part in the 2000 torch ceremony decided to do his stretch in a tractor instead of on foot.

Before yesterday, the flame had gone out just twice. It was extinguished by a sudden downpour in Montreal in 1976, when a worker scandalously relit it with a cigarette ligher, forgetting the pagan mystique involved; it should have been relit from a back-up torch. In 2004, it was blown out by a gust of wind. Yesterday's events pushed the number of such mishaps from two to five, making the President of the IOC, Jacques Rogge, furious.

"Violence for whatever reason is not compatible with the values of the torch relay or the Olympic Games," he said. Someone should have told Adolf Hitler.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments