Where are the heroes to speak for the disenfranchised like Muhammed Ali? There have been none

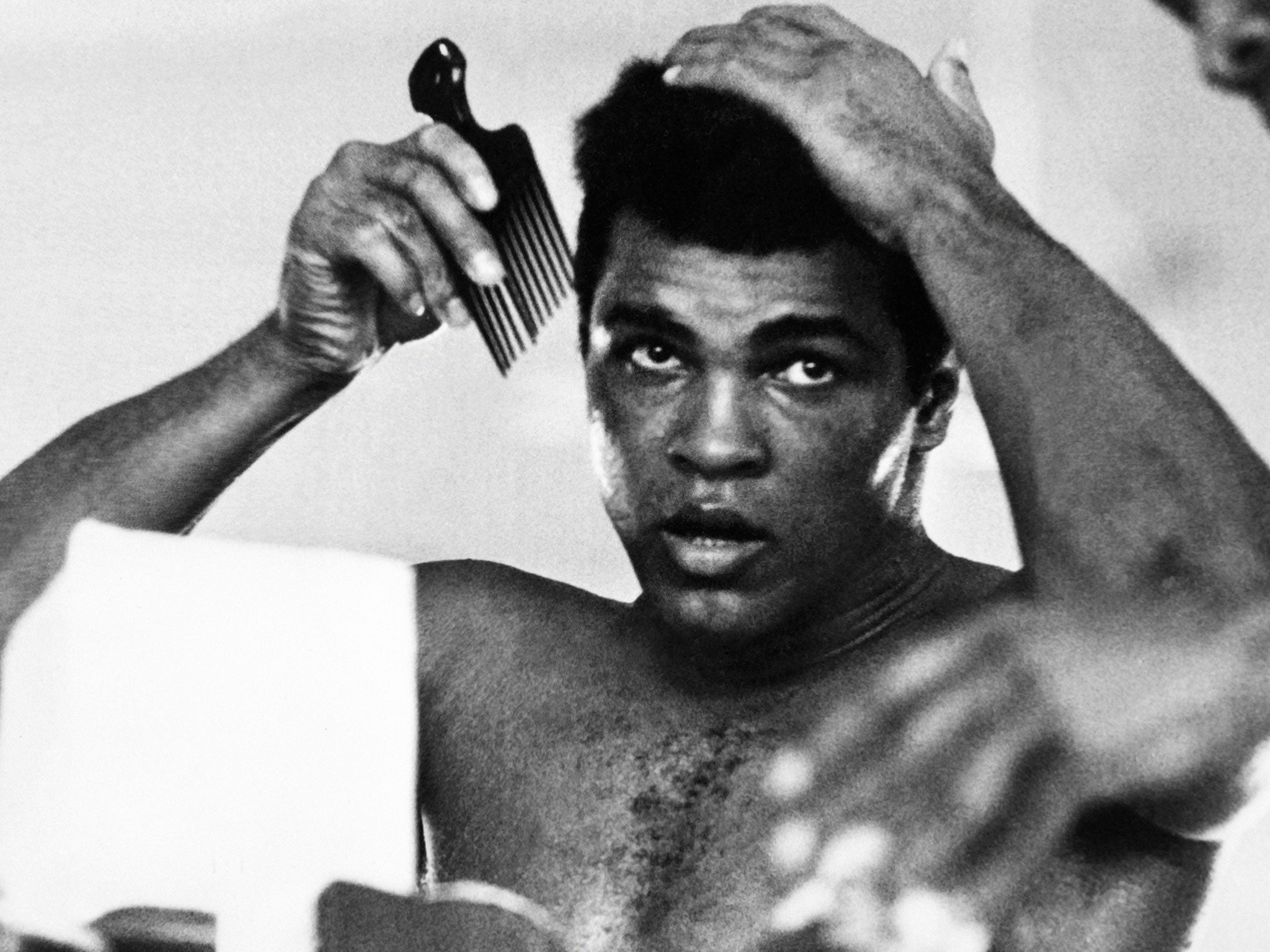

The boxer transcended sport like none other

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He spoke the unspeakable in a way which marked him above all others who have commanded sport’s great stage. That’s why Muhammad Ali leaves such a monumental vacuum behind for those of us who chronicle sport in the here and now.

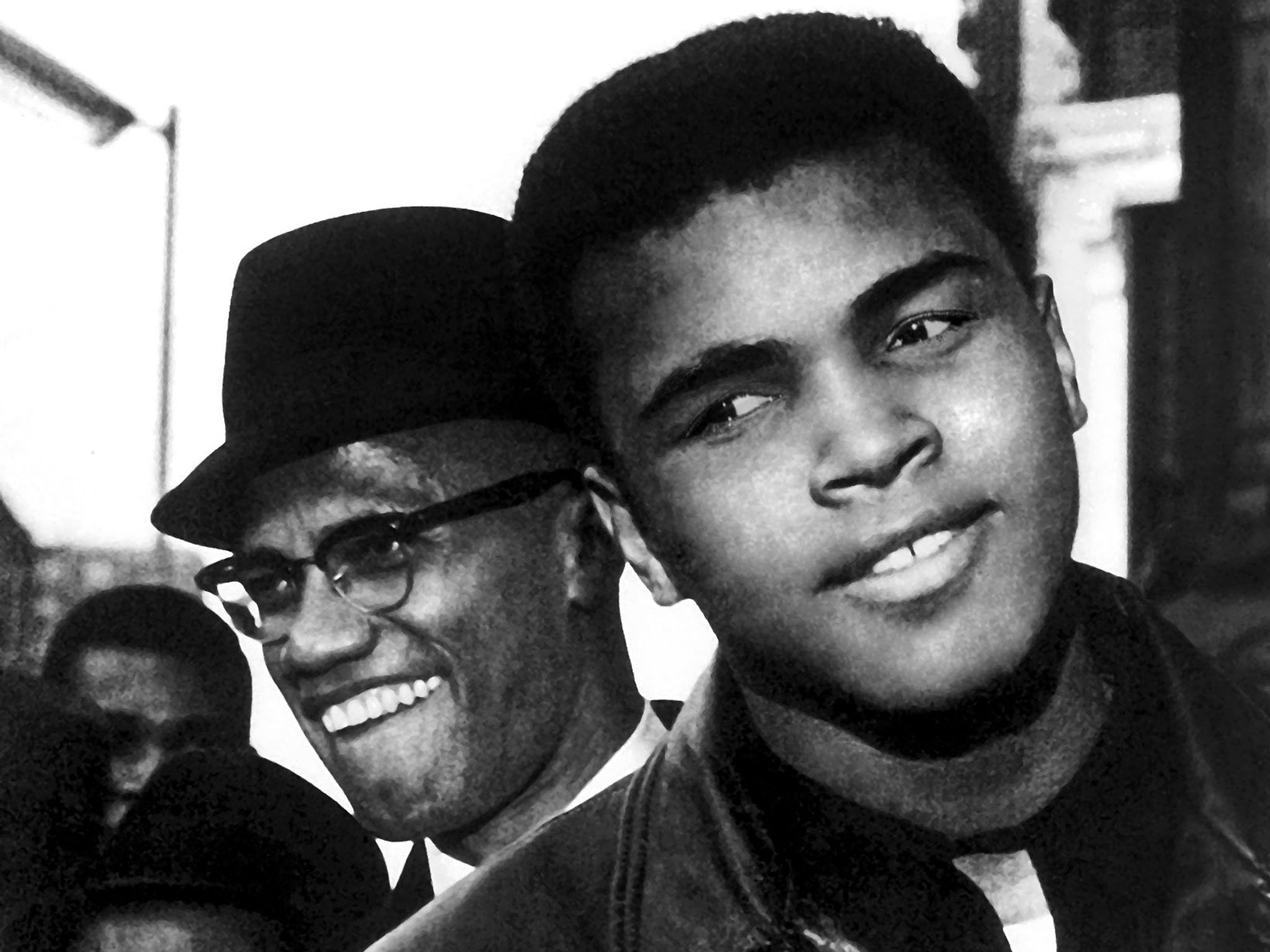

The power to inspire through words was never instilled in him by an education system: that is the greatest irony of all. Ali was only semi-literate and when he was ordered to undergo a 50-minute written examination at an Army induction centre in 1964 registered a score so low that they declared his IQ to be 78, said he was ineligible for active service, and even retested him to make sure he wasn’t feigning ignorance. Needless to say, he wasn’t.

This embarrassed him - questions of his own minimal education always did – so he hit back with humour. “I said I was the greatest,” he told reporters. “Not the smartest.” When American troop levels in Vietnam escalated to such levels that he qualified for service after all, journalists beat a path to his door, sensing a big story about a world champion being drafted at the peak of his career.

“What do you think about the war? What about the Vietcong?” one of them asked him – and quite honestly, Ali stumbled, because he didn’t know what he thought of the war or of American president Lyndon B Johnson or of Vietnam. “Man,” Ali said eventually, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.”

Those eight words, uttered by an American world champion, were sensational, went around the world, and yet were no more than a blurted piece of improvisation. “When he was thrust into the middle of the national agony, he reacted, as he did in the ring, with speed and with wit,” as the writer and journalist David Remnick put it.

Ali’s rejection of the draft was an even more dangerous and high risk stance than his rage against the injustice of the nation’s racial divide had been. It provoked a visceral response from America and its journalists and saw him stripped of his WBA title and an income he desperately needed. So where, you wonder, is that same spirit of courage and principle among those who now command the world’s attention through sport. Where are the carriers of Ali’s torch?

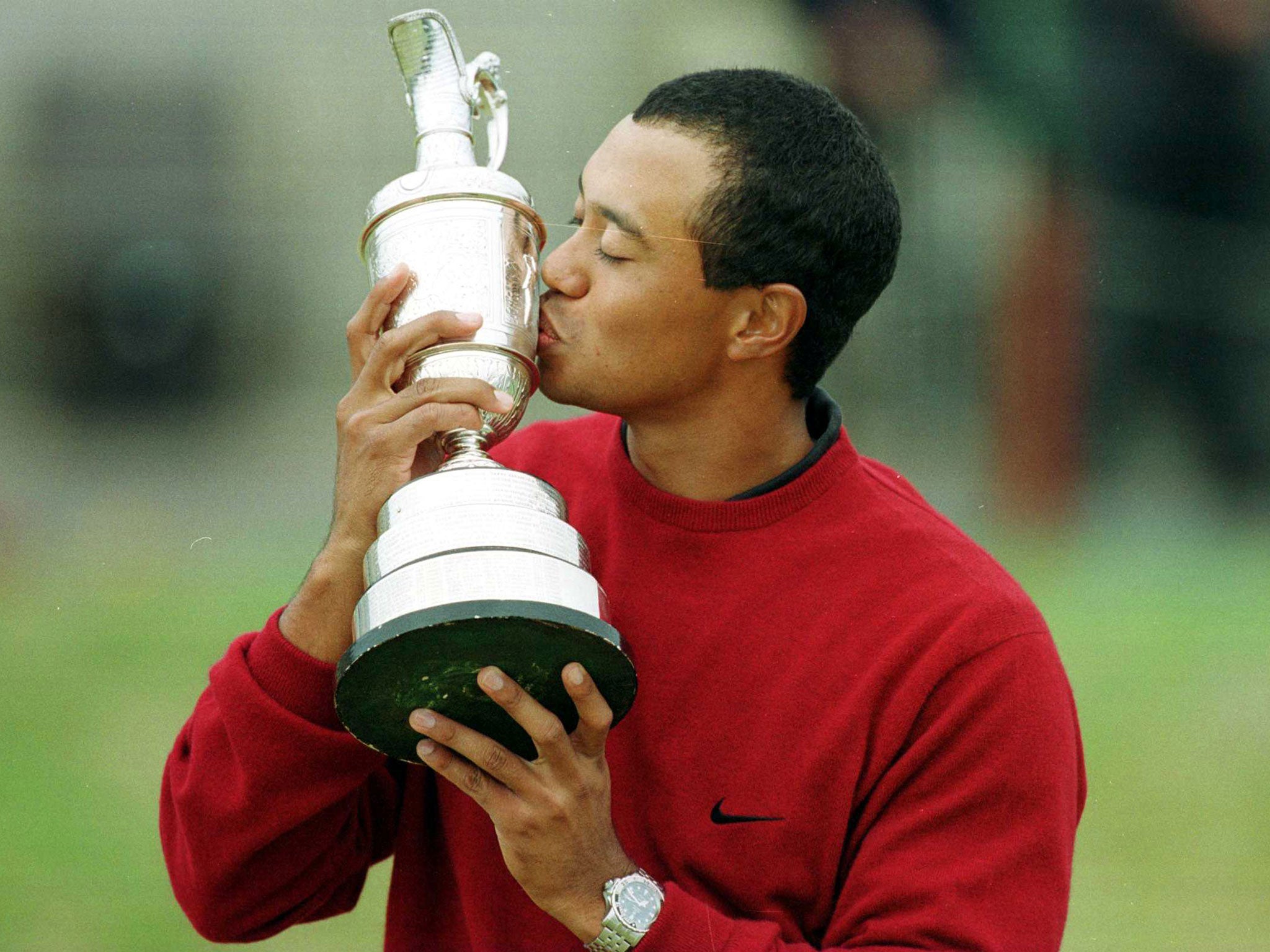

There was a time when we thought Tiger Woods might be the great voice of the disenfranchised in his own dismally mono-cultural sport, yet that hope has long since evaporated; drowned by his pursuit of less spiritual goals. The Masters is a white man’s game. The black people sweep the Augusta National club’s carpets, serve lunch and then leave work for homes on the impoverished other side of the tracks. There has been the same deafening response to racial iniquities from basketball’s Michael Jordan. A friend asked him why he wouldn’t endorse a black Democratic candidate in 1990 North Carolina Senate race. “Republicans buy shoes too,” he said.

The reluctance to touch anything remotely political exists within British shores, too. Football carries a wealth beyond Ali’s comprehension yet when this correspondent sought those from that sport to articulate the need for compassion for refugees seeking British sanctuary last year, there was nothing. Word came back from one whose family had actually experienced asylum that they did not want to “rock the boat.”

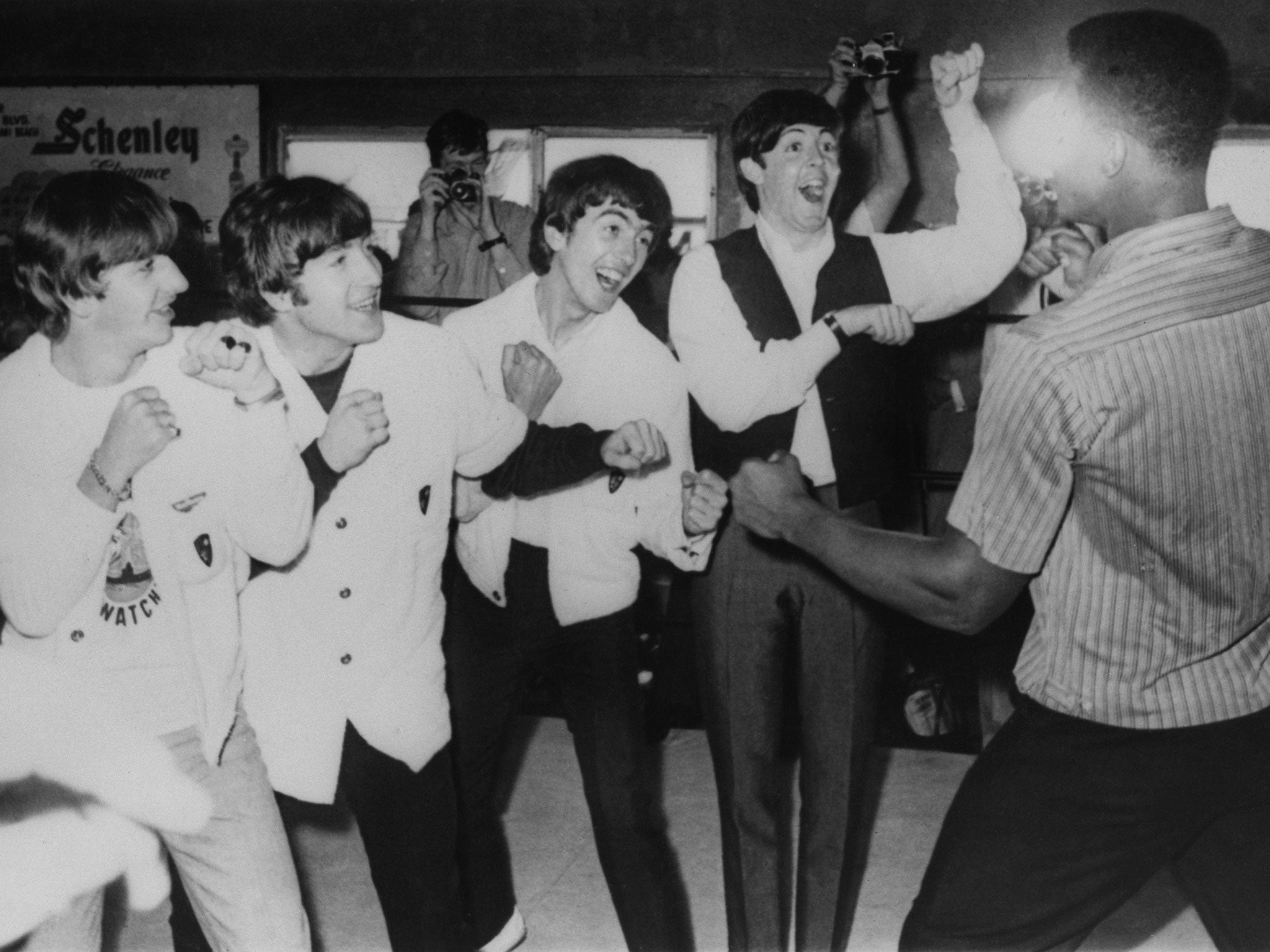

No-one wants to do that, it seems. There are vastly more people paid salaries to anaesthetize and make safe the words of today’s competitors than there are competitors to utter them. It is a choreography and control which was unknowable to Ali - supreme and quite beautiful incarnation of spontaneity, as he was. He spoke and competed off the cuff. To hell with what people thought of him for that.

At Manchester’s Moss Fire station boxing club, an unprepossessing little place bursting with life and ambition, you saw yesterday that this is why Ali has continued to speak to so many down the years of his own years of physical deterioration. Vast images of him overlook the ring where young men and women seize the sport as a channel for their lives. It is still the humour of his message that screams out to them. “Some of it was just the ultimate trash talking; just brilliant trash talk,” says 16-year-old prospect and ABA youth championships fighter Malakai Dixon. “He used it to make people hear the things that mattered. In a small way, I think I’m here because of him.”

Dixon, like everyone else around here, loved what they saw of Ali for his beautiful moment, his incredibly fast feet and his combinations, but most of all because he made him smile with such a

glorious lack of self-importance. When it became known that the club was the place BBC Radio 5 had made the focus of conversation and memories about Ali on Sunday morning, people dropped in to talk. A schoolteacher, Sandra Smith-Brown, spoke of sitting up with her late father, Wintie Smith, a coal miner, willing Ali to win on the televised fights because of the sense of the soaring belief he had created in their predominantly black community. Sometimes the fight would still be going on when she, still a child then, departed to bed. Mr Smith would tap on her door as he departed for the mine the next morning. ”He won the fight! He won the fight!” he would whisper to her.

They loved Ali because he spoke for them but also because he saw a world of need beyond his own ego.

Ali saw a world beyond his own ego. It’s why his job was done long before he was lifted for the last time from his rocking chair beneath the shady trees of his ranch at Berrien Springs, Michegan, last Thursday. “You don’t own nothing,” he once said. “You’re just a trustee in this life.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments