Meet the holistic guru who is helping Mo fly

Anti-gravity treadmills and recovery chambers are two innovations Alberto Salazar has used to turn British distance runner Farah into a world-beater

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There's something different about Mo Farah these days. It should be evident in the Stade Louis II stadium in Monte Carlo tonight when the matchstick man from south-west London, by way of Mogadishu, lines up for the 5,000 metres in the Monaco leg of the IAAF Diamond League series.

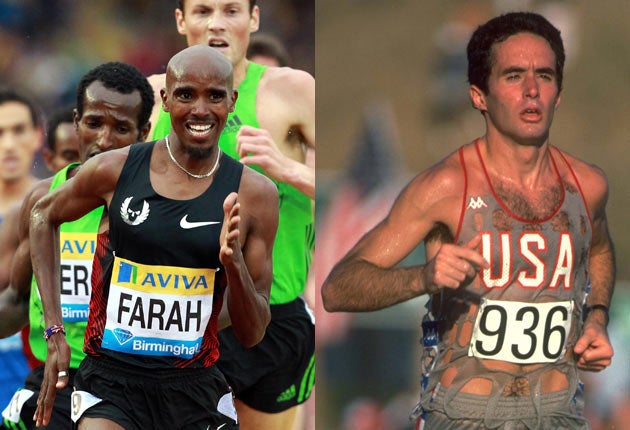

It was certainly clear for all of the sell-out 12,500 crowd to see at the Diamond League meeting in Birmingham a fortnight ago: the confidence, the assurance, the eye-of-the-tiger look about Farah as he spreadeagled a world-class 5,000m field. He looked like he knew he was going to win, even before he made his decisive move just before the bell.

The reigning male British Athlete of the Year burnt off the opposition with a final lap of 54.03sec. Miruts Yifter did the same to Steve Ovett in the 5,000m at the Gateshead Games in 1977, clocking 54.6sec for the final 400m and earning the sobriquet "Yifter the shifter" from David Coleman in the BBC television commentary box. Two years later, the little Ethiopian shifted his way to Olympic 5,000m and 10,000m gold in Moscow.

Only five other men have ever achieved the coveted "distance double" on the track in the Olympic arena: Hannes Kolehmainen in 1912, Emil Zatopek in 1952, Vladimir Kuts in 1956, Lasse Viren in 1972 and 1976, and Kenenisa Bekele in 2008. For all of Britain's distance-running heritage, no one from these shores has ever won a single Olympic title at 5,000m or 10,000m. The last medal was Mike McLeod's 10,000m silver in Los Angeles in 1984.

A year and five days out from the 2012 Olympics, the Somalia-born, London-raised Farah is looking a promising bet for a place on the podium at his hometown Games. On form, thus far in 2011, he has become the global leader in the distance-running game. For that, the 28-year-old Briton can thank the Cuban-born, American-raised distance-running guru who was described on the front cover of The New Yorker last November as "a revolutionary running coach". Alberto Salazar's unorthodox, ultra-holistic approach to the elite group of distance runners he guides at Portland, Oregon, in the north-west of the United States – with his underwater treadmills, his anti-gravity treadmills and his Cryosauna recovery chamber – has clearly had a positive effect on Farah.

At the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene on 3 June, he smashed the British and European 10,000m record with a time of 26min 46.57sec, and smithereened a field that included a host of elite East Africans – among them Imane Merga, the 2011 world cross-country champion and world No 1 at 5,000m in 2010, and another Ethiopian, Sileshi Sihine, runner-up to Bekele in the last two Olympic 10,000m finals.

If that was a clock-chasing mission impressively accomplished – one that left Farah at the top of the world rankings in 2011 – the 5,000m in Birmingham was a tactical exercise executed with eye-catching precision. He hit the front with 420m to go, stretching away from Merga, then kicked again with 200m left. He covered the final mile in 3min 59.8sec.

Last summer, Farah won at his leisure against the best of the rest of the continent in the 5,000m and 10,000m at the European Championships in Barcelona. Twelve months on, a month out from the World Championships in Daegu, South Korea, the Arsenal fan is doing so against the global big guns – well, the biggest apart from the Ethiopian Bekele, who has been out of commission because of a knee injury since early last year.

Undoubtedly, Farah has gone up a notch in class this year. He has stepped up to the global plate and delivered. He has done so under the direction of the tall figure in the baseball cap who stood checking his lap times as he performed a high-tempo training session for 45 minutes after his 5,000m win in Birmingham.

Since January, Farah has been guided by Salazar. In his own running days, when three times a winner of the New York City Marathon, Salazar was renowned for pushing himself to the limits in training and in races, and going to extraordinary lengths to maximise his talent legitimately. He attempted to mimic the effects of training at altitude by rigging up a scuba-type mouthpiece that used chemical crystals to absorb oxygen. To help his muscles recover from the rigours of training, he rubbed them with dimethyl sulphoxide, a lotion used by racehorse trainers to reduce inflammation in thoroughbreds.

As coach to an elite group of US distance runners, plus Farah, at Nike's headquarters on the outskirts of Portland, Salazar uses all manner of space-age equipment to supplement the staple diet of 100-plus miles a week that his charges clock up in regular training. As well as the various treadmills, the Cryosauna blasts liquid nitrogen at up to -300F, while he also has shockwave therapy machines. "It's like in war," Salazar says of a training programme that has been dubbed "the Oregon Project". "The soldier has to learn how to fight and do everything – be physically fit, be a one-man army. But then you try and equip him with every bit of top science – everything you can – to keep him alive. That's what we do. We use science, every bit that we can, on top of old-school training. We are going to train as hard as anybody else, and then we're going to train more by adding things that don't get us injured. And we're going to train smarter than anybody else."

In Farah's case, that smartness will include preparing him for the mental pressure of returning to London as a big home hope on the Olympic medal front a year from now. Salazar could give a personal insight on that score, having been one of the favourites for the 1984 Olympic marathon in Los Angeles. He wilted in the Californian heat, finishing 15th.

"That's an area in which we can help Mo a lot," Salazar says. "He needs to prepare for the kind of pressure that is going to come with being a Brit at the 2012 Olympics. It's natural there's going to be pressure on athletes when they're competing at home, and the athlete has to understand that. I can get that across to Mo from my experience: 'Hey, look, it's going to be there, you're going to feel pressure.' It's impossible to block it out but you can't dwell on it. You've got to focus instead on what you're doing in training, your preparation. This is another area where we have something to offer. We have a sports psychologist who works with every one of our athletes. Actually, he's a Brit – Dr Darren Treasure. I look at the mind as being another part of the athlete's weaponry. They have to get to its maximum potential."

Salazar: A matter of life and near-death

Alberto Salazar was born in Cuba in August 1958. He was brought up in Wayland, Massachusetts – the home town of Steven Tyler, the frontman of Aerosmith.

Salazar won the New York City Marathon in 1980, 1981 and 1982. His winning time in 1981, 2 hours 8 minutes 13 seconds, earned him the status of world-record holder, eclipsing the global mark of 2:08:33, established by the Australian Derek Clayton in Antwerp in 1969.

In 1984, the New York course was remeasured and found to be 148m short, the equivalent of about 27 seconds. By that time, Salazar was struggling with injuries and on the wane but he still entered marathon history as one of the all-time greats.

As a coach, his successes have included guiding Kara Goucher to the 10,000m bronze medal at the 2007 World Championships and Dathan Ritzenhein to third place in the world half-marathon championship race in Birmingham in 2009. His training group in Portland also includes Galen Rupp, runner-up to Mo Farah over 5,000m in Birmingham two weeks ago.

In June 2007, Salazar was felled by a sudden heart attack. He had no pulse for 14 minutes but survived. Now 52, he jogs four miles a day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments