Latest drug scandal to hit Germany dates back to 1960s

On the eve on the new Bundesliga season, German sport is once again under intense scrutiny over its use of drugs after latest investigation exposes West Germany

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

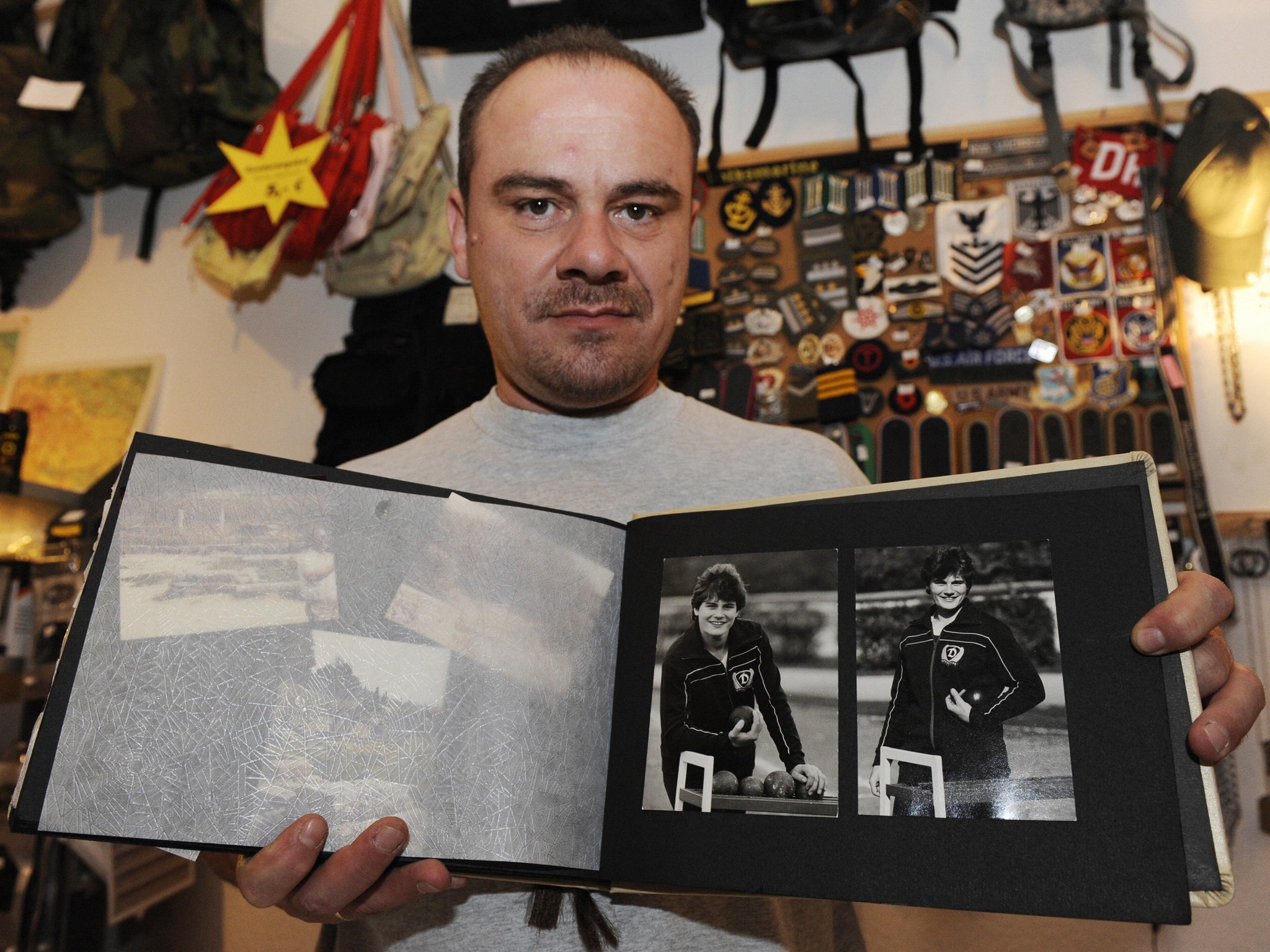

Your support makes all the difference.There is no more powerful an example of the corruption in East German sport than Andreas Krieger. At the age of 16, Krieger was a woman named Heidi, an Olympic shot putter, and already a victim of the East German state's relentless doping regime. The sheer quantity of anabolic steroids with which she was injected during her career led to her body slowly developing male characteristics, until in 1997 she opted to undergo gender reassignment surgery.

Krieger is just one of many whose lives were irrevocably changed by the East German drive for success on the world stage. The Stasi files, released after the Wall came down, contained damning reports of the extent of the GDR's doping program, led by Sports Minister Manfred Ewald. For the enduring West and later unified Germany, it was more proof of the rotten nature of the communist state.

Rarely, though, can the moral comparisons between East and West be so firmly set in black and white. And on Monday it was conclusively shown that the world of sport is no exception. In a study rather depressingly entitled “Doping in Germany from 1950 to present: a historical-sociological study in the context of ethical legitimation”, it has been revealed that doping was nearly as prevalent in West German sport as it was in the grey, moral wasteland of the East.

In 800 pages (of which only 117 have been released to the public eye), researchers from the Humboldt University in Berlin and the University of Münster detail the extent to which anabolic steroids, testosterone and EPO were used in West German sport. From as early as the 1960s, the report reveals, the use of such substances had begun to emerge, with doping becoming a major issue by the 1970s and 80s. Nor, it seems, was this an issue limited to athletics. Among the myriad athletes implicated, three members of the West German World Cup squad of 1966 were also discovered to have traces of ephedrine in their blood. Most importantly, the report suggests, is that the rise of doping coincided with the founding and development of the government funded State Institute for Sport Research (BISp).

Germany is no stranger to doping scandals. Aside from the shame of Jan Ullrich and the acid tongue of Robert Harting, the country's first World Cup winning side of 1954 was also accused of having utilised performance enhancing drugs for their miraculous Final victory over Hungary. That particular case – and now that of '66 – however, will never rank among the most disturbing of accusations. Defending his former team mates this week, Franz Beckenbauer reminded us that “at that time we didn't even know what doping was. I was there. The word didn't even exist yet.”

Certainly, the report has a point when it claims that “doping is a phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century” and it is this which raises the biggest issues for Germany and German sport. For while there will be individual Lance Armstrongs and Jan Ullrichs in every country on earth, the damning aspect of the “Doping in Deutschland” report is that the rise of doping was linked to research financed and supported by the state itself.

In a clip shown on ZDF last weekend, former German Olympic Team Doctor Joseph Keul is seen telling cameras in the seventies that “in particular, we are looking at ways in which the performance of a human being can be medically improved. What is possible and what can be used without harming the athlete.” It is an innocent enough statement out of context, but alongside the work of the BISp, it makes for uncomfortable viewing from a modern perspective. That the research carried out by such people should have been funded by the government itself makes it even more so.

Studies from BISp in which the study of various drugs were clothed in euphemism such as “Substitution” and “Regeneration” are, the report says, “to be seen as practically oriented doping research, the results of which were subsequently put into practice.” It goes on to suggest that many athletes “saw themselves as having no choice but to dope” during the 1980s.

The involvement of the State is what makes this case so striking. In a recent interview with Deutschlandradio, former SPD politician Walther Tröger declared that „doping was researched on the request of the government. Everybody knew that.“ There is a fear that, should Tröger's assessment prove correct, more details will come to light in the rest of this report which would expose the Federal Republic as having been just as guilty as its communist neighbours. The single difference being that in the West, they did not record every injection quite so meticulously.

Among those who may be dragged into the political mire is current Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble. Once hugely involved in sport politics, Schäuble's is one of few names to have actually emerged from the report – and with it has come a wave of speculation as to how many blind eyes when it came to doping. Shortly before the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, Schäuble is alleged to have said that „so long as it doesn't harm them, we should give our athletes whatever is best“.

For those at the German Olympic Committee (DOSB), BISp and other bodies involved in the commission and publication of the report, there remains a key difference between the doping programs of East and West. General Director of the DOSB Michael Vesper was keen to insist to SID that „we cannot compare what happened here in the West with what went on in the GDR – namely state organised doping programs carried out without the knowledge of the individual athletes.“ He was also understandably quick to remind us that it was the DOSB and the government itself who had backed the commission of the report in the first place, and criticised the manner in which certain newspapers had treated the story, saying „We want to draw our own conclusions."

It is easy to sympathise with Vesper's appeal for a bit of patience. As with all such cases, much of the coverage remains reactionary, and it is perhaps best to concede that, for the moment, there is not enough information in the public sphere to justify the condemnatory tone of comparisons with the GDR. As far as we know, there are no cases such as Andreas Krieger in relation to the West's approach to doping.

For many, though, even the limited information we currently have is enough to suggest a betrayal on a level far beyond expectation. That the West did not record their actions so rigorously only serves to cast more doubt on how much more is always to be revealed. And it certainly blurs the often unfairly well defined lines between Good and Evil, and between East and West.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments