West Ham to leave Boleyn Ground: How the club was the heart that drew local communities together

Hammers play their final game at the ground next Tuesday before move to Stratford

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

It was the Roman Catholic community of Upton Park who helped West Ham United to find their home there, on the site that they will leave next week after 112 years. And that community, along with the others with whom it shares space, will still be there, left behind, when the football club moves.

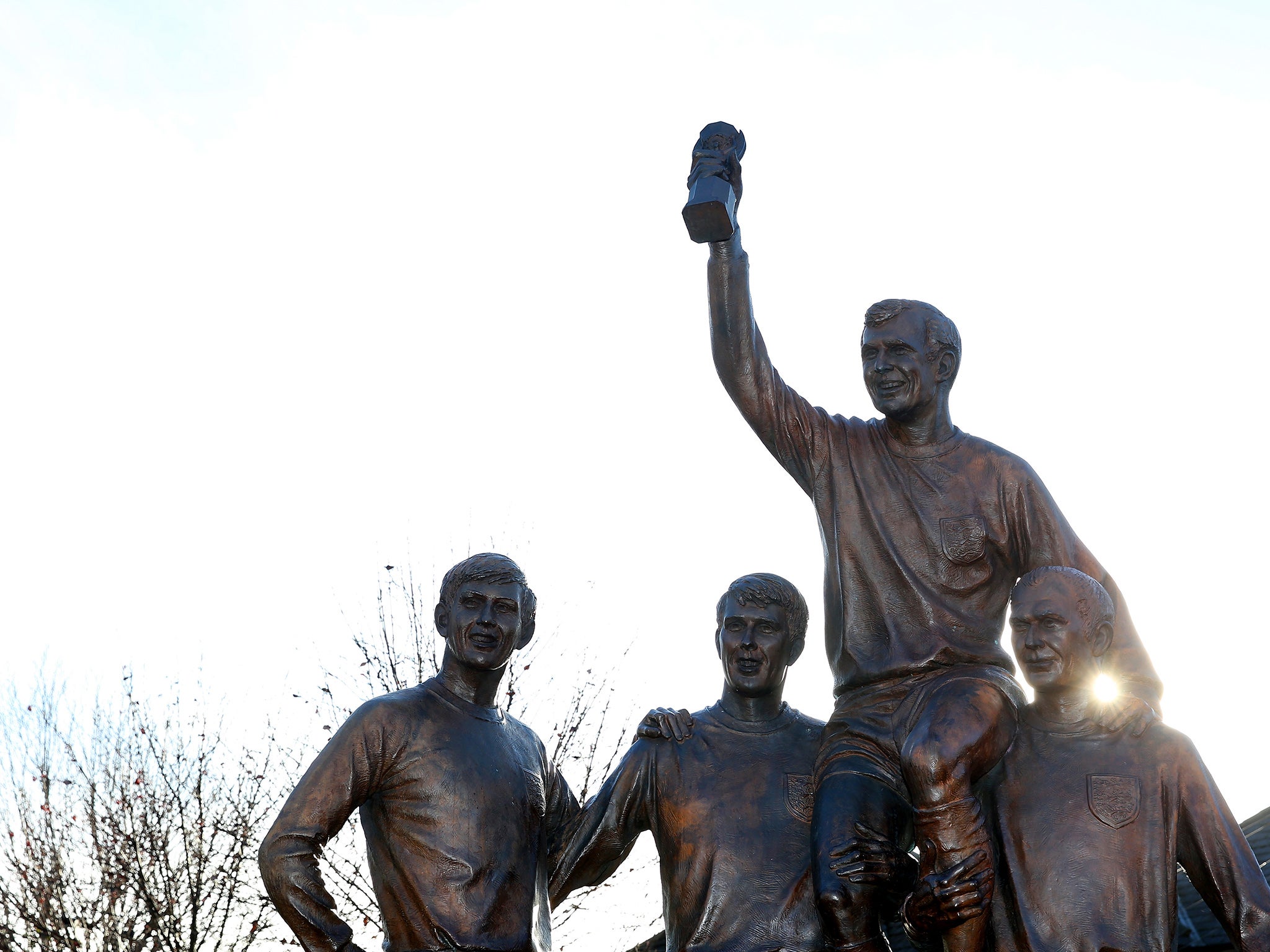

West Ham United, of course, have always played in that corner of east London, ever since they started in 1895 as Thames Ironworks FC in Canning Town. For 10 years they bounced around grounds but in 1904 they found the sympathetic figure of Brother Norbert, a teacher at St Edward’s Reformatory, a school for Catholic boys who had fallen into trouble.

St Edward’s was based on Green Street, on the old Boleyn Castle ground and, fortunately for the football team, they had green space, even if it was known as the ‘Potato Field’. West Ham rented it from them and their first game at the Boleyn ground, on 1 September 1904, was against Millwall. In front of a crowd of 10,000 people, West Ham won 3-0.

That was a crowd of local working people – gas workers, dock workers, iron workers – who wanted social institutions of their own and were prepared to work hard for them. So it was for the local Irish catholics, who wanted a church on the site that they owned, backing onto the land that they leased to the football club. With dedicated fundraising they found the money and in June 1911, the Church of Our Lady of Compassion was opened.

That church is still there on Green Street, although the football ground now towers over it. But the two places have seen in their centenary, serving the local communities which built them up. These are the types of place that lives and families cohere around, and their two stories have always been intertwined.

When the football ground was hit by a Nazi V1 rocket in August 1944, all the windows of the church were smashed, tiles were blown off the roof, doors unhinged, and the altar damaged.

While the football club bought the freehold for the land from the church in 1959 – for £33,750 – the tie between the two places has been as strong as ever. They share the same land, which means they share the same people. Long-standing parish priest Father John King is a West Ham fan from Barking. Joey O’Brien and Slaven Bilic are both observant Catholics who go into the church to pray, Bilic wearing his religious bracelet from Medjugorje, the town on the border between Croatia and Bosnia, where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to six schoolchildren in 1981.

Not every church would want to be next to a football ground but at Our Lady of Compassion the bond means a lot to them. The church is home to two nuns – Sister Immaculata and Sister Patricia – who have directed a house of prayer across the road since 2000. “If Jesus came to the earth today in person,” they were told, “he would go straight to the east end.” They had some understandable apprehension about life on the doorstep of a 35,000 crowd, but were told by Father John they would always be safe.

Since arriving in the area to teach, the sisters have taken the football club to heart. “We have been almost sucked into West Ham, as a hoover sucks one in,” Sister Immaculata says from her Green Street prayer house. “We love the people, all of the scenery, all that goes on on the day of a game.”

“Football is just wonderful, to see life, to see joy. Many of these people have been carrying pains, but in that moment, one does not see that. Always joy and happiness, people munching their burgers. The little children, teeny-weeny things holding their grannies’ hands, some even in little push-chairs. It is life, it is innocent, it is clean and it is wonderful.”

With their own rituals, their calendar, and their sense of communal magnetism, the religious community sees a version of itself in the football club. “We feel at one with them,” Sister Immaculata says. “I have never said ‘it’s a match-day, what a nuisance.’ It is so lovely, bringing life here. When we go out to teach at St Michael’s [in East Ham], on our return, we smell the burgers, we see men selling scarves and programmes. The noise is there, but we enjoy it. It is not a noise that is not welcome. It is a welcome noise, a happy noise. We would love to be out there with them, making part of the noise ourselves.”

Of course, people move, areas change, and no-one would suggest that Upton Park should stay frozen as it was 100 years ago. It has diversified and there are more communities there than ever before. The catholic community itself has changed and grown: it now includes Filipinos, Ghanaians, Ugandas, Indians, Tamils, Poles and Lithuanians. The fifth mass on a Sunday at Our Lady of Compassion is now in Polish. There are also services in Malayalam for the Indian catholics.

These changes have enriched the life of the church too. In 2005 mass attendance figures were at 1500, the highest in the recorded history of the parish. The recorded local catholic population in 2009 was higher than ever before.

But change can make places poorer as well, especially when that many jobs, that many people, that much meaning is moved three miles away. The football club and the church have grown up together but only one will still be here in August, 112 years after Brother Norbert told West Ham secretary Syd King about the sports field at the back of his school.

“It is going to kill the area,” Sister Immaculata says. “It is almost wrenching a community, it is very sad. West Ham was the heart that drew these people together.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments