Project Big Picture: Why sooner or later English football needs to change

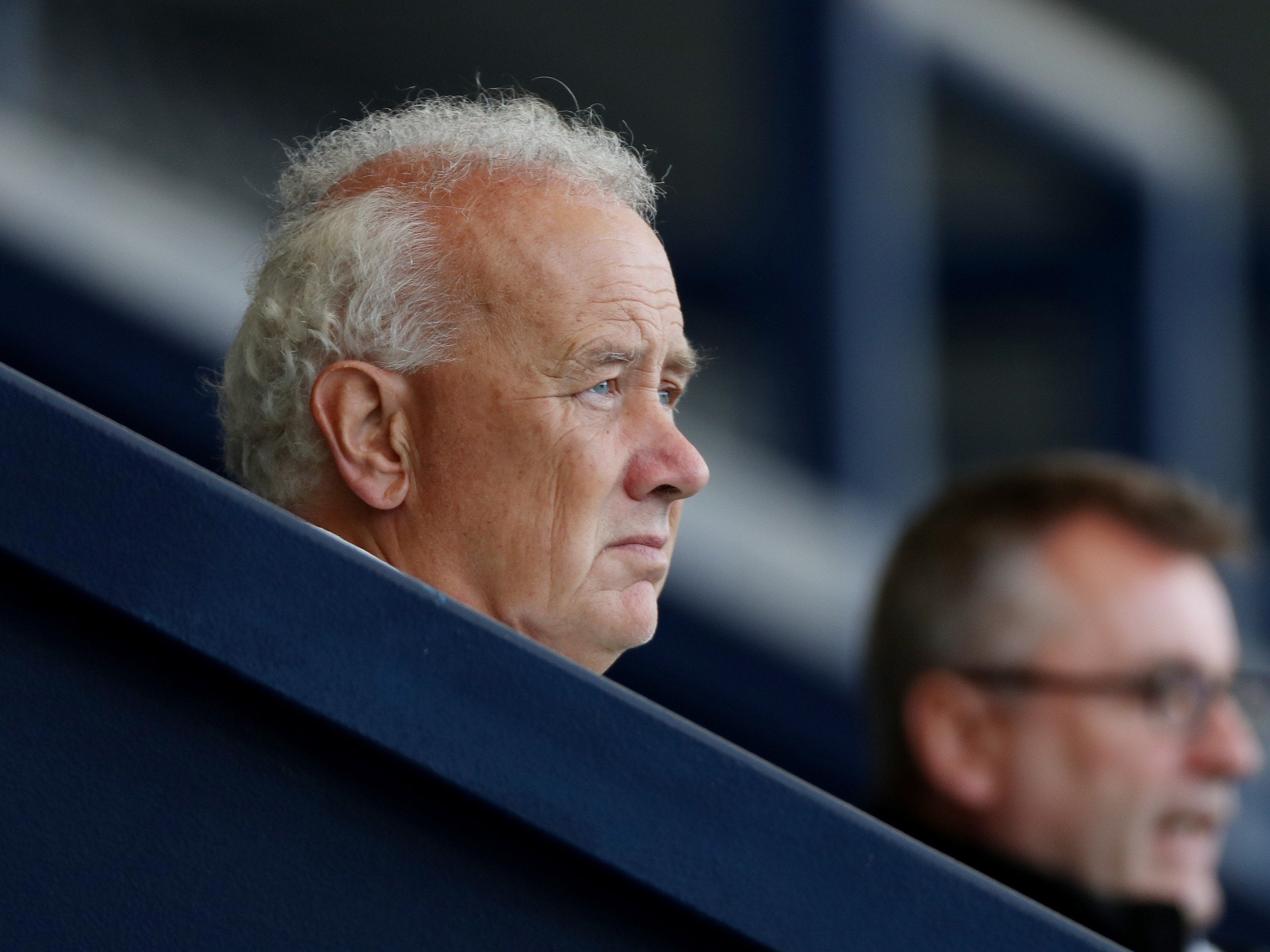

Rick Parry’s controversial proposal may not necessarily be the answer but as distress calls sound across the game, a new vision for English football’s sustainable future is undoubtedly needed

Rick Parry was at home when the phone rang. John W Henry was on the line. Liverpool’s principal owner was watching a documentary in Boston and a familiar face came on the screen.

The programme was about the laboured birth of the Premier League in 1992. Parry was the organisation’s founding chief executive. Henry made the call. The American sounded surprised. Was Parry really the man who helped create the monster? Henry said they needed to talk.

The conversation amused the man who would become chairman of the EFL. Of course Henry knew about Parry’s past. The two men have had a relationship since the Boston-based billionaire bought Liverpool a decade ago. Parry, as a former chief executive at Anfield, had provided advice, local intelligence and the benefit of his knowledge to the new owners. Henry had just forgotten. Get over to the States, Fenway Sports Group’s leader said. We need to talk.

The conversation – which never actually took place during Parry’s subsequent whirlwind trip to New England – was about a restructuring of the economy of the domestic game. Henry had been pondering football’s finances for more than half a decade. His exasperation was palpable.

Project Big Picture is the fruit of that frustration. As early as 2012, Henry was telling acquaintances that the sport’s fiscal basis was fundamentally flawed. It annoyed the 71-year-old that little more than a handful of clubs in the Premier League drew global interest. The Big Four, Five or Six – it changed over a decade - paid the bills. It was hard to see the point of the likes of Blackburn Rovers, Blackpool, Wigan Athletic, Birmingham City, Stoke City and half a dozen other clubs who came and went from the top flight. In American terms, the division was stacked with minor league clubs playing in the majors.

What Henry found particularly annoying was that teams in the bottom half of the table seemed to have little more ambition than avoiding relegation and pocketing the television cash. Parachute payments fostered a ‘bare minimum’ ethos and warped competition in the Championship, too.

The flip side of this is that a 20-team league of doughty battlers who fight tooth and nail to stay up means life is exacting for the teams in the Champions League places. Playing English football, even against the ‘lesser’ sides, is demanding. The elite, Henry figured, were getting the worst of both worlds.

The battleground manifested itself in the argument over overseas broadcast rights. The big clubs felt sharing the money equally was unfair and began a campaign against it. There were clandestine meetings in New York to discuss strategy but the fellow malcontents – Manchester United, Manchester City, Arsenal, Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur - had narrower aspirations than Henry. He did not want a bigger slice of the money. Revolution has been on his mind for a long time.

Those more familiar with English football’s past – with Parry at the forefront – explained that there was an element of Groundhog Day in Henry’s thinking. Yet the Boston Red Sox owner would not let it go.

He was talking about handing 25 per cent of the Premier League’s annual revenue to the EFL eight years ago. The money would ease the fears of the top-flight’s bottom dwellers and make the Championship less about the biggest spenders. At least in theory.

When Parry became EFL chairman last year, the 65-year-old’s prime objective was to restore some financial sanity to the lower leagues. With his vast experience of football administration, Parry planned to curtail the worst excesses, especially in the second tier, and introduce a salary cap. Then Covid-19 hit the game hard.

The pandemic presented an opportunity. Since March, the EFL chairman has talked about this being a chance to assess the direction of the sport and ask whether there is a better way. Henry’s thinking dovetailed. Both men have had massive input in Project Big Picture.

Joel Glazer also believes in the concept. The United co-owner has stridently supported the idea and even tried to convince other Big Six executives that the pyramid is crucial to English football’s future. The thought of a Glazer being the flagbearer for the game’s infrastructure is mindboggling. Cynics see this as an opportunist attempt to use the pandemic to grab power. Even the elite clubs have mixed feelings.

Spurs are broadly supportive. Arsenal, Chelsea and City have concerns. The Premier League clubs threatened with the removal of the one-club, one-vote system are furious.

Henry and Parry – and Glazer, too, no doubt – genuinely believe that they are proposing the best deal for English football. Parry fears that Coronavirus will hasten the decline of smaller clubs and have an adverse impact on communities across the country. Henry thinks an 18-team Premier League and a wider dissolution of broadcast revenue would benefit all parties. The quid pro quo is that those with the most financial muscle want the most influence.

The situation is so desperate in the EFL that the majority of clubs would take the £250 million short-term bailout money and, with reservations, accept a quarter of the Premier League’s annual income.

The top-flight clubs who would lose their voting power are less inclined to agree. The public are suspicious of change. No wonder, after a week where pay-per-view raised its ugly head and fans feel they are being railroaded into spending £14.95 to watch individual televised games that are played behind closed doors, on top of their hefty Sky and BT subscriptions.

Project Big Picture was leaked and its authors were not ready to make their case. That put Parry in the line of fire. With hindsight, Henry and Glazer might have been more proactive and announced these ideas in a staged setting rather than let it seep out in the media. Nevertheless, Henry and – in particular – Parry have the game’s interests at heart.

Revitalisation may not be the way forward but the sport cannot continue to operate blithely in its pre-Covid dreamland. Change needs to happen. Sooner rather than later.

Liverpool, United and the EFL have attempted to bypass the inertia and provide a roadmap for the future. It is flawed but is a basis for dialogue. Those who object need to offer their own vision of a sustainable future.

Distress calls are going off across the game. The crisis can no longer be ignored.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies