Why Arsene Wenger's second decade was not as good as his first, as others have established their supremacy

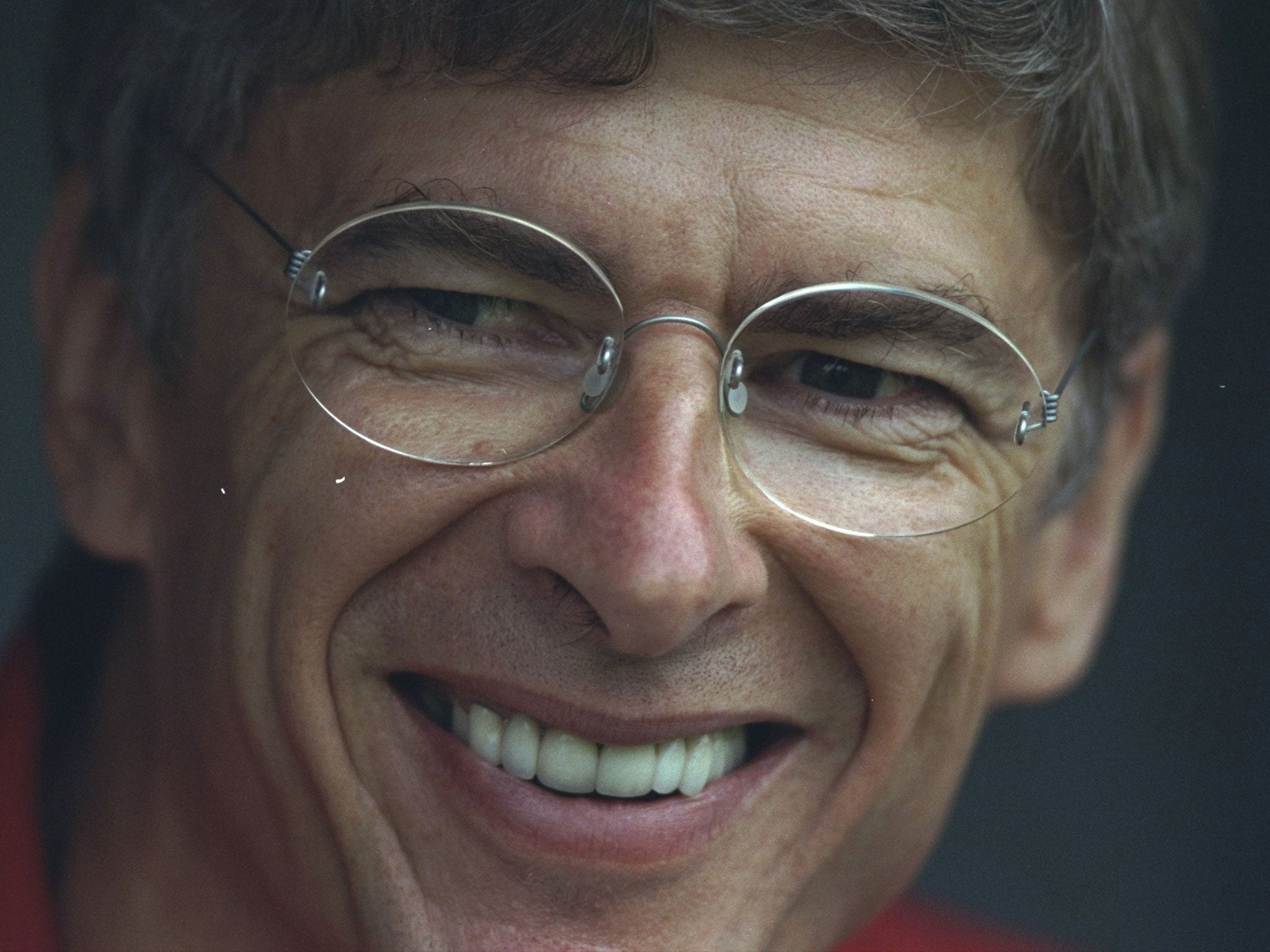

Twenty years on from when the Frenchman was unveiled as the Arsenal manager, Jack Pitt-Brooke looks back at a career defined by glorious highs and disappointing lows

Arsene Wenger, at his best, was a visionary, but he was never an architect. His football is not mapped out, but based on freedom and trust. It is based on having players good enough and clever enough to express themselves on the pitch.

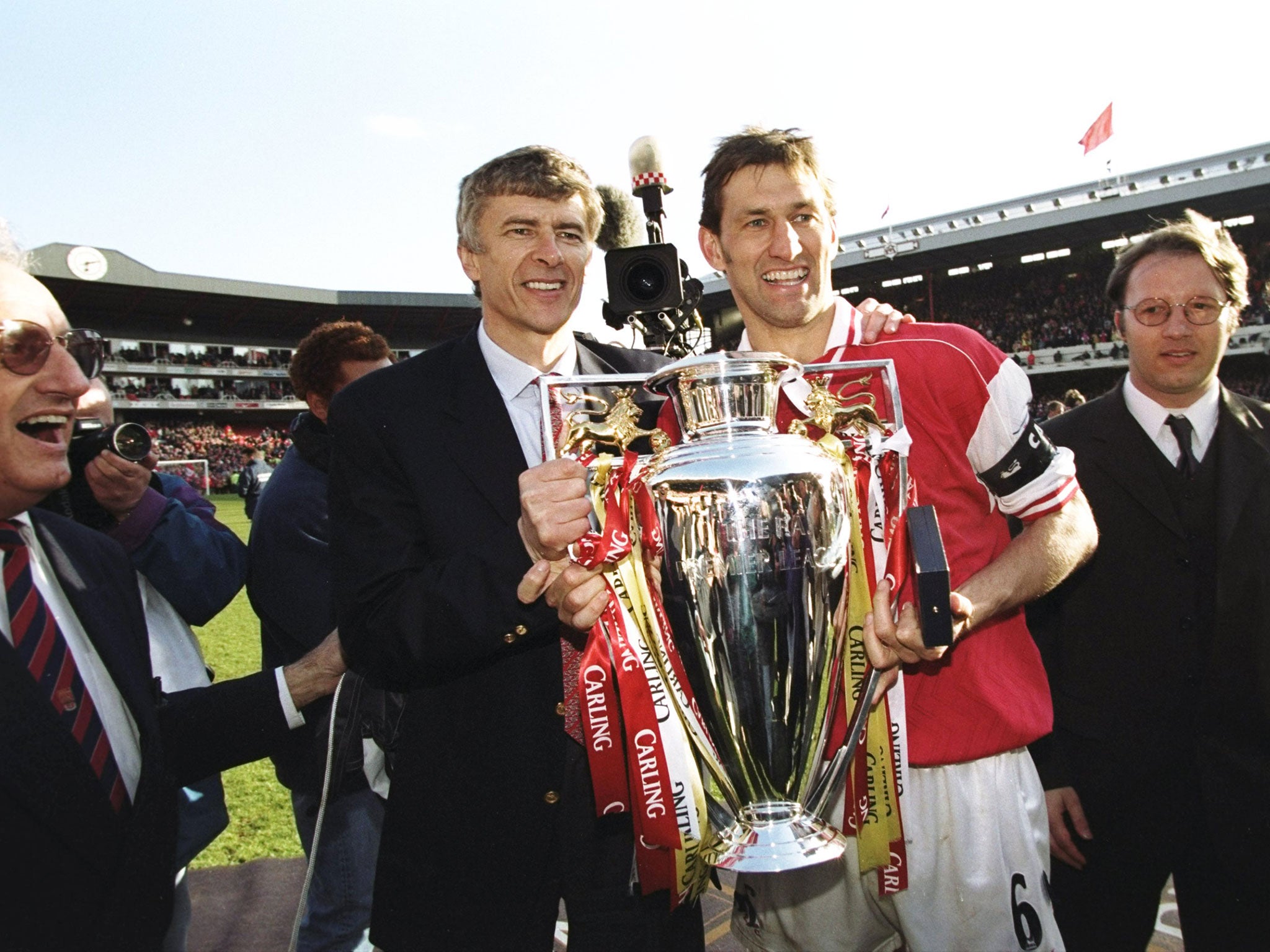

That was the method that Wenger arrived with, 20 years ago this week. The method that won Arsenal three thrilling titles in the first half of his reign. But no different from the method that has delivered none since the Invincibles, over 12 seasons ago.

If the first half of Wenger’s reign was one epic duel with Sir Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United, the second has been more about Chelsea, their opponents on Saturday. The arrivals of Roman Abramovich and Jose Mourinho, at the beginning and end of the Invincibles season, saw Chelsea raise the bar at the top of English football. They set a standard which was taken on by Manchester United and then Manchester City. Arsenal have never caught up.

That Chelsea team that won four Premier League titles, four FA Cups and one Champions League was built on a core of experienced driven powerful senior players, who enforced standards on the pitch and in training. They were Mourinho’s apostles and they kept his spirit alive long after he was gone.

Arsenal used to have a core like that too. They had their own powerful players, some that Wenger inherited, then some that he bought in. They set the tone and instilled the values. They were the rock of Wenger’s own church.

Everyone knows about what Wenger changed when he arrived at Arsenal, but just as interesting is what he kept the same: George Graham’s English defence. “Arsene came in, but the standards were still being set by players who had been there before, winning silverware under different managers,” recalls Nigel Winterburn, one of the leaders in Wenger’s first four seasons.

These were the players who had something to pass on to the new recruits: first Patrick Vieira, then Emmanuel Petit, Nicolas Anelka and Marc Overmars, then a 21-year-old Thierry Henry. “I remember Henry spoke of the English spirit when he arrived, in Tony [Adams], Steve Bould, Martin [Keown], Lee [Dixon] and myself,” Winterburn says. “If you didn’t know anything about Arsenal Football Club, you were made to understand it very, very quickly when you trained with the senior players. We hated losing any game. That made them understand what we were all about.”

Those English players moved on, but Vieira and Henry were the new leaders of the team, preserving the flame for the next generation. It was the perfect place for a young player to learn. “As a reserve, training and playing alongside Martin Keown and Sol Campbell was brilliant,” remembers Danny Karbassiyoon. “Just as eager as they were to win the next game, they were also eager to help you out. When I moved from striker to left-back, I needed help on positioning or on one-on-ones. When the ball went out of play, Sol or Martin would come over and tell me. They didn’t need to do that.”

What stands out is the clear sense of responsibility felt by these Arsenal players, to push each other to ensure they were as good as they could be. These were the players who, after only winning the FA Cup in 2003, turned their celebration party into an inquest into why they did not win the league too.

“They went out of their way to corral the next group, to tell them what it takes to win,” Karbassiyoon says. “When we played 5-a-side, Keown, at 36 or 37 years old, would be furious when we lost or conceded, yelling at the team, firing everyone up.” And if it was not Keown, it was Vieira, Henry, Campbell, Dennis Bergkamp or almost anyone else. They were hard on each other and hard on themselves.

This environment of winners was exactly what Wenger needed, precisely the type of players he could trust and inspire. Wenger did not need to hammer the players in the dressing room or on the training ground, because the expectations were already in place. One former senior player once joked that Wenger “could not coach his way out of a paper bag”, but in truth he did not often need to. Players were trusted to solve problems themselves, and to interpret the manager’s ideas on the pitch.

The problem was what happened next. Chelsea and Arsenal were going in opposite financial directions. Abramovich’s unprecedented spending helped to build a team that established their mid-decade dominance. Arsenal’s stadium move meant they did not have the money to replace like with like. They built the new ground just as the foundations of the team were eroding. Almost the whole team went, taking their experience, nous and, most importantly, their standards with them. Wenger replaced old players with young ones but left them stranded.

“We passed on the history of Arsenal Football Club, of what it meant to play for them, to the foreign players that came in,” says Winterburn. “Then Thierry, Patrick and those players took it on. But when they went, the history of winning trophies goes, along with the knowledge to pass on. That made a difference.”

By the time Arsenal moved to the Emirates Stadium, which brought its own financial constraints, the club was a very different place. The big players had gone, and what was left? William Gallas was an unconvincing captain and was eventually replaced by Cesc Fabregas, who was just 21 years old. Up front they had Nicklas Bendtner and Emmanuel Adebayor, two talents in need of guidance, but the guidance had gone.

This sudden change in profile was clear when Arsenal met Chelsea in the first big game of their post-experience era, the 2007 Carling Cup final. Wenger’s youngsters lost their heads and lost the game to a Chelsea side that, with Petr Cech, John Terry, Frank Lampard and Didier Drogba, was already two league titles into its development. It was maturity against immaturity. “They had lots of experienced players, and we had quite a lot of younger players at the time that hadn’t been what the Chelsea players had been through,” says Justin Hoyte, who played at right-back for Arsenal that day. “Maybe that’s what got them over the hurdle. But credit to Wenger for giving us the chance.”

This could have been a learning experience, but the problem is that there was no-one left for Arsenal players to learn from. Wenger had a clearer idea than ever of the football he wanted to play. But he did not have the candid vocal senior players to make sure that it happened. He was the only voice left in the room.

“Vieira put that winning mentality across to everyone every day,” remembers Hoyte. “It was hard when he left because he was such a big character. If you had that Vieira figure there now, he would be an older player to guide and encourage the younger players. They are missing someone like Vieira or Henry. If they had that now they’d be at the top of the game, winning leagues again.”

Arsenal’s leaderless team could easily have won the title in 2008, 2011, 2014 or 2016. In all four years they were well set with a few months left, but the players just did not know how to get over the line. There was no-one there to show them how to. “It has never really been a coaching culture at Arsenal,” says one source close to the squad. “But now it isn’t a winning culture either.”

While Wenger committed to stability, Chelsea showed that strong squads still win trophies even while the manager keeps changing. In March 2012, after Andre Villas-Boas was sacked, Wojciech Szczesny said that “some of the English lads at Chelsea pretty much run the club”. It was meant as a dig, but two months later those English players had won the FA Cup and the Champions League.

No era lasts forever and that great Chelsea generation has almost gone the way of the Arsenal team from 10 years before. But they have maintained a psychological edge over Arsenal and Wenger even as their own big players have drifted away. Wenger’s 1000th game as Arsenal manager will forever be remembered as the afternoon when they were steamrollered 6-0 at Stamford Bridge. Even last season, when Arsenal finished eight places and 21 points ahead of Chelsea, they lost to them home and away.

The old drive, the refusal to lose, the candid accountability, has all gone. “If things are not going right, is there someone willing to really demand something from their team-mates, without the worry they might upset them,” wonders Winterburn. “When you look at Arsenal and they concede a goal, of course they care, but no-one seems to make eye contact. They put their heads back down, and walk back to the half-way line, ready to kick off again.”

With financial restrictions relaxed, Arsenal have bought their own senior players in recent years and they are the ones who have flourished most, delivering consecutive FA Cups in 2014 and 2015. This is the oldest and most experienced Arsenal team since the Invincibles. But there is a difference between age and title-winning expertise. Wenger has found that once something has been let go, it is hard to get back.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments