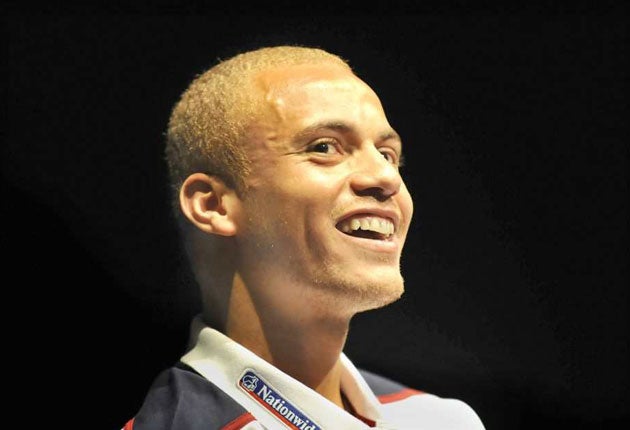

The making of Wes Brown

From one of Manchester's roughest districts to the toughest character at Old Trafford – the local boy has come a long way. But the past year has presented his greatest challenges yet. He talks to Ian Herbert about the loss of his father and half-sister, and the mentors who shaped his life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Only the Stone Roses saw artistic merit in the place that Wes Brown will always call home. They found it in the girl there who, Ian Brown once told us, would "move like a queen of Longsight, M13." The life of Markfield Avenue, an unprepossessing terrace, is much like any other street in the district and that includes its occasional brushes with the gang warfare. The Longsight Crew are as much in operation as ever and it is just over a year since shots fired in the street killed a 23-year-old at a funeral wake.

The street will always have immeasurable meaning to Brown though. He is to be found there pretty much every other day, visiting his mother, Ingrid, and perhaps indulging the occasional thought for those days when, with two back garden walls for goals, grass in front of each and "a road in the middle" where the imaginary centre spot used to be, he and the street's early 1990s generation played "shooting" as they called it. There were no particular rules. "Except you weren't allowed to use your hands in net," Brown recalls.

The draw of the place has become stronger than ever in the past eight months. Brown has been twice touched by tragedy in that period of time, first mourning the death in February of his father Bancroft, a driving force behind his arrival in the game, and then learning, during United's summer tour of South Africa, that the half sister he had only just begun to know had died three months into a pregnancy. Brown was granted compassionate leave to fly home to join the family.

The United and England defender has not spoken before now of his father. But as he does so after a visit to a Manchester school for an event supported by the Team England Footballers' Charity in which the value of family bonds is being reinforced among children, the role which his father played in illuminating the lives and taking young people off the streets and into football becomes vividly clear. "If he saw a kid and knew their mum or dad he would ask them if they wanted to try football training. He was good like that," Brown says, his characteristic calm demeanour disguising some of the obvious pain of his loss. The memories flood back: of his father, a huge United fan, driving him to the Football Association's Centre of Excellence at Lilleshall or else packing hordes of Longsight lads into his car and heading for the Fletcher Moss Rangers club on Sunday mornings. "That carried on even when I had got in at United. He wanted to get them all into football and doing something, instead of hanging about and messing about," Brown says. Sir Alex Ferguson has more to thank him for than most. Danny Welbeck, who was aged six when Brown was braving the cauldron of a Leeds match at Old Trafford on his United debut, would be in that family car most Sundays too. He made a sharp Old Trafford debut in the Carling Cup win against Middlesbrough last month. Next on the production line is Brown's brother Reece, aged 16, another United Academy player.

Family ties still mean everything in an uncompromising place like Longsight and that is why Brown's discovery eight years ago that he had a half-sister Claire Fallows (his father's daughter) was so important. She wasn't in and out of the house every day, in keeping with the rest of clan, as she lived in Burnley "which was hardly next door," as Brown says. But there was a bond. "She was a great woman, a top girl. It was mostly weekends that she would come down. She might come to my dad's or to my sister's." Ms Fallows, was 36 and three months pregnant when she died in hospital. For Brown, who admits with characteristic understatement that this period "hasn't been easy" for any of them there is at least the comfort of continued contact with her three sons. "If you stay together you are strong," Brown says.

That is an ethos which has served him well throughout a career which, despite Brown's fulfilment of the rich potential Ferguson always spoke of, has had some hateful moments. Two wrecked cruciate knee ligaments and a fractured ankle cost Brown the entire 1999-2000 season, plus the European Championship that followed and parts of 2002 and 2003.

It is a message he wants to convey to the children of Abraham Moss High School in Crumpsall. Brown was there for the Team England Footballers' Charity in association with the PFA, to support the vibrant past week of campaigning by the Kick It Out anti-racism campaign. The charity was established after the England squad resolved to donate their match fees – roughly £1million – to good causes ahead of the 2010 World Cup. Those benefiting will be the Professional Footballers Association charities, the Bobby Moore Fund for Cancer Research UK, Children's Hospices UK, Well Child, as well as the players' own Outreach Programme for inner-city projects.

"The thing that football's told me is to keep your chin up when things aren't going your way," Brown tells the children "To find the people you know you can talk to and to let them help you find a way through. You never know what lies ahead."

The last part is also certainly true of Brown's formative years after he had left St Chrysostom's CE primary school, a few hundred yards from his own front door, for Burnage Secondary, when football was hardly at the forefront of his mind.

Ask Brown who he looked up to there and you might expect him to say his football coach. But the inspiration was the man whom he knew only as 'Mr Williams' (inquiries later reveal he answers to the name Graham) – the deputy head and basketball coach. It was basketball, not football, which the Burnage boys lived and breathed and Michael Jordan who was foremost among Brown's heroes. "There was a school football team," Brown says. "But basketball was every day and football was every now and again. Football came more naturally. We were just all friends in that team, we all enjoyed it and were pretty good." Good enough, in fact, to win the English schools' basketball final circa 1995. That day all passed in a blur, but the sense of what it means to bring silverware back to inner city Manchester has lived long.

There were footballing heroes in those days, too, including Ryan Giggs. "He's my all time best player so to be playing with him is unbelievable for me. He's been around so long now and his achievements are the best. I'm just so glad he's still going."

The United men were also still his heroes as he graduated through the United Academy, where he had arrived aged 12, though those were days when a real hierarchy still existed, apprentices cleaned the first-team's boots and Brown was allocated Eric Cantona's. "There were two jobs for me actually," he recalls. "The other one was cleaning out the gym. I know the lads don't do it anymore but it was good. It showed you respect for the older players and it put you in your place and told you that you'd not made it yet and had a long way to go."

There were no conversations with the Frenchman whose boots he polished before the 1996 encounter with Roy Evans' Spice Boys. "You just didn't speak when Eric was about. If he came into the gym you sat back and he did his own thing. He was that kind of a person. He walks in a room and you go a bit quiet." Even now, with 21 England caps to his name and seemingly a firm place in Fabio Capello's set-up, "Hello, how are you?" remains about as bold as Brown gets when he sees Cantona around Old Trafford.

But a hard district breeds tough souls and at the uncompromising Manchester United school Brown won respect for his unstinting, tough tackling and calmness on the ball. The social breakthroughs started coming when he had made it to the reserves and found himself with players like Giggs and Paul Scholes. "It tended to be the ones who hadn't played at the weekend. Even when a few of the first team spoke to you, you didn't quite know what to say but they made you feel like you'd arrived." United's French defender Laurent Blanc, an important influence, made him feel that way too. He was the player who, amid the fury of a game found time to make suggestions. "He'd say: 'Maybe you can open up. You don't have to do this, you can do it this way. Just little things. If it was Jonny Evans, Danny Simpson or Rafael [da Silva] today, I hope I'd do the same."

And suddenly, without ceremony and almost without notice, Brown has become one of the bastions of United. His performances might not leap off the pitch as do those of Rio Ferdinand but, with Gary Neville's prolonged absence he featured more regularly than any other player at right back last season. The battles he has always waged have not stopped. After months of negotiation, he finally secure the £50,000-a-week contract last April which will keep him at the club until at least June 2012. Tough times demand tough performances, too. Two mighty displays at centre back, his preferred position, against Barcelona in the Champions League semi-final told Ferguson all he needed to know before the deal was signed.

Neville's return from injury and the emergence of Brazilian Rafael da Silva present new challenges, but Ferguson indicated yesterday that Brown will be back in the United starting line-up at Everton today. "It's Wes's turn," he said. On Tuesday night, Neville threw Brown the captain's armband when he left the field against Celtic. "Didn't think that much of it. It's usually the oldest player who'll get it," Brown said. His heart might still be in his home street but he's travelled a long way from Longsight M13.

My Other Life

I'm really into my boxing – always have been – and I was lucky enough to be ringside in Las Vegas when Ricky Hatton fought Floyd Mayweather back in December. It's a passion I share with Rio Ferdinand and Wayne Rooney and we all know Ricky well. Perhaps the reason why I follow the sport is that I was so keen at karate when I was a boy. I became a brown belt in no time but at the age of 11, I had to choose between karate and football. I've always been an all-round sport nut. The interest I have in basketball began when I played at secondary school and for me one of the great sporting legends will always be Michael Jordan. I've always enjoyed cycling too, and one of the memories of growing up was the day I rode between Manchester and Blackpool to raise some money – I think my mum said it was £300 in the end – for the premature baby unit where my brother Clive was born early.

Old Trafford's local lads

Manchester United may be historically famed for its youth policy but as the standard required to make the grade, or even enter the academy, has risen it has become increasingly rare for local lads like Wes Brown to progress into the senior team.

In the season Brown made his debut 11 players born in Greater Manchester played for United. Three of them, Brown, Gary Neville and Paul Scholes, are still in the first team set-up 11 years later but the only other Mancunian in the squad is rookie striker Danny Welbeck. Another youngster, Salford-born Danny Simpson, played last season but is currently on loan to Blackburn Rovers.

1997-98

Wes Brown Manchester

Nicky Butt Manchester

(now Newcastle United)

Michael Clegg Ashton-under-Lyne

(now retired)

Danny Higginbottom Manchester

(now Stoke City)

*David May Oldham

(now retired)

Gary Neville Bury

Phil Neville Bury

(now Everton)

Paul Scholes Salford

Ben Thornley Bury

(now retired)

Michael Twiss Salford

(now Morecambe)

Ronnie Wallwork Manchester

(now unattached)

2008-09

Wes Brown Manchester

Gary Neville Bury

Paul Scholes Salford

Danny Welbeck Manchester

*May was not a product of United's youth system.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments