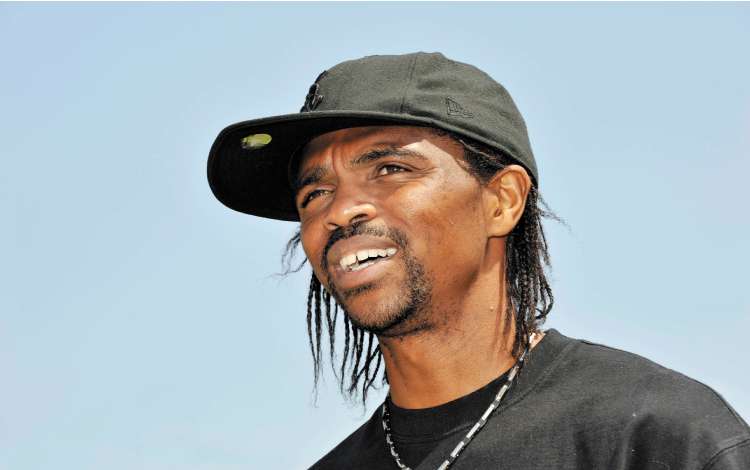

Nwankwo Kanu: 'For years African players have been exploited...'

Portsmouth's Nigerian centre-forward knows better than most how badly treated footballers from his continent have been. He tells Jason Burt why he is establishing a foundation to help them do something about it

"Kanu is not only about Nigeria, Kanu is big across Africa" – Portsmouth midfielder John Utaka.

And Nwankwo Kanu wants to be big for Africa. The 30-year-old Nigerian, twice African player of the year, Olympic Gold medallist, European Cup winner with Ajax, League and Cup Double-winner with Arsenal – and FA Cup finalist with Portsmouth tomorrow – has decided to use this interview with The Independent to launch his own football foundation. It will, Kanu claims bluntly, take on "agents who have for years preyed on young African players, ripping them off and leaving many penniless and abandoned".

He goes further. Kanu, the most fêted of African footballers, has pledged to set up his own academies across the continent – starting in Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Somalia – because he does not believe that the ones already in existence are good enough or act in the interests of players and their families. Kanu also wants to advise the football federations of these countries on how to educate and teach youngsters and coaches so that they are looked after properly.

And that's just for starters. Kanu already has a heart foundation, named after him, which has been working for the past eight years to save the lives of hundreds of children who need surgery. He now wants that, too, to go further. Instead of flying the patients and their families out of their homelands for their operations he wants to have five hospitals built – in Nigeria, Ghana, Rwanda, Ziwbabwe and Uganda. And for them to be built within the next 18 months. "It's possible," Kanu says as he explains his hugely ambitious plans. "A lot of companies want to get involved and it can be quick to build things in Africa. They know we can do this."

The Kanu Football Foundation, he says, will be free to use. No charge. Players and their families, their advisers, will be able to call up a dedicated telephone line and ask for help. "In Africa," Kanu says, "the young players have to go through a lot of things, many of them they don't know how to deal with. So the foundation will advise and help them out. When they come to a big league, like the Premier League, we can advise them before it's too late."

What qualifies him for the role – Kanu says he is simply formalising something he already does as "people call me all the time, even when I'm travelling, they come to my hotel and ask for help" – is, of course, his unrivalled wealth of experience. "I've been through a lot and played for a long time so I can understand what others will go through," he says. "That's why I want to help them out. There are a lot of players who go to Belgium, for example, and have had terrible experiences. I know players and they have come to me. We need to make sure they have more support and that will make their families happier because they know they are being looked after.

"The foundation, I hope, will be a big organisation covering lots of different areas and whatever help the players need then we can direct them in the right way and give them the best. A talented footballer comes over, his family depends on him and if his agent or club don't treat him well he might not succeed and then he feels he's let everyone down. For years, African players have been exploited. I know a lot who have suffered and the foundation is going to have a big responsibility."

It is a thorny issue. Stories exist of young players – kids really – taken out of their homes with the promise of making it big in Europe only to fail and be abandoned. Too ashamed to return home, having failed to realise their family's dream, they drift. And then there are the players who do make it but are badly treated. The Cameroonian Georges Mojado, for example, moved to RAEC Mons in Belgium when the minimum wage was €1,075 (£855) a month. He was paid €150. Timothée Atouba – who once spent a season at Tottenham Hotspur – previously played for Neuchâtel Xamax in the Swiss league. There he was paid a third of the wage stipulated in his contract and only after a year did he obtain two-thirds. During that time his complaints were allegedly met with threats to send him back to Cameroon.

"The problem is everyone wants to play football," Kanu says. "Some are lucky, some are not. But we will be open for everyone to call us. I believe that because of my name and who I am and what I have done that they will want to listen." The foundation will be a joint venture with NVA management, a company run by consultant Chris Nathaniel, whose clients include Rio Ferdinand, Micah Richards and Kanu's fellow Nigerian Obafemi Martins. All are supportive to his plans.

"Everything starts from a small step," Kanu says. "We know it's going to be difficult because there will be some resistance. But if we start right now then we can get things in place. When good things are coming there are always some people, who haven't been doing good, who will try and stop it. But if you believe in what you are doing and are strong enough then you achieve it. People know who I am and what I have done.

"Some people will be suspicious but they always are when you try and change things. That's what can happen in Africa. But when they see what we are doing then hopefully that will change. I don't want to keep quiet and let what I have been doing for so long die. It's good for me to come out with something like this. And I think clubs will back it because it's a good idea and when we have the academies also – they will be everywhere – then that will help the clubs."

One of his biggest – and most controversial – complaints is to question whether players need full-time agents. "I think you need people who can advise you, that is more important that an agent," Kanu says. "They are important because they help players move but I have some experience of agents working with players who have done things not to help the player but to help themselves." He prefers the way Spanish and South American footballers work in using lawyers or business managers.

The issueof how to deal with the exploitation of young African players is not new. Fifa has been discussing it for years with its president, Sepp Blatter, at one time provocatively accusing European clubs of acting like "neo-colonialists". Football's governing body wants to see the improvement in domestic leagues, and has poured money into its "Goal" project, and while Kanu agrees with that he also claims it is unrealistic to expect players to shun more lucrative offers overseas. "When there is no money people don't want to stay," he says, "but I hope the foundation will advise leagues and associations on how to improve. We do have to find local stars for local leagues so that people can aspire to be them also. But I have to admit that everyone is interested in the Premier League."

The success of Kanu's Heart Foundation suggests that he can make this venture work. "So talking about football, that's where my talents are, then I think I can do even better than with the Heart Foundation," he says. If Kanu succeeds it will be some achievement. The foundation started in 2000 following his own well-documented heart problems. In the summer of 1996, after leading Nigeria to Olympic Gold, with some superb goals and a string of assists, Kanu was set to be star of Serie A after securing a big-money move to Internazionale.

The 6ft 5in striker was already a double-European Cup finalist – and winner, in 1995, against Milan having also secured three Dutch league titles with Ajax. Aged 19, the world was at his, fairly substantial, feet. Instead a medical at Inter, having already signed and played in pre-season friendlies, showed he had a faulty aortic valve. "When it happened the doctor said to me 'you can't play football again'. It was the end of the world. I was scared. But I'm a Christian and I prayed that God would help me," Kanu says. "The first thing was to have the operation [four hours of open heart surgery in the United States] and once that was successful I never believed I would not play again."

A career was not lost but 14 months, the time it took for him to rehab, was. Inter moved on. They signed Roberto Baggio and Ronaldo and, after just 11 games, Kanu had to move on, too. To Arsenal – for the £4m it had taken to transfer him from the Netherlands to Italy. "My heart problems changed my aspect on life," he says. "If you have been in hospital for that kind of thing, then it does. No one knows what the future holds and maybe that's why I started to think about others more. When it happened it helped me understand what life was all about. I've always taken responsibility but only when something like that happens can you really see."

One day, soon after signing for Arsenal, Kanu was watching television. It was about the problems of heart surgery, the waiting lists, the operations that needed to be done. The idea of setting up a foundation was born. It started by raising money for two young Nigerian children – Oluwatofunmi Okude and Enitan Adesole – but that was expensive, costing £15,000 each, with the operations in London. Soon children were being taken to Tel Aviv and then Miot Hospitals in India. Two hundred and ninety lives have been saved. "But the main aim of the foundation now is to have hospitals built in Africa," Kanu says. "I know it's going to cost a lot of money." He is looking for companies to help fund the work and take on the naming rights while a charity dinner will take place in London in September to really kick-start the campaigning.

"I get hundreds of letters from all over Africa and that's where the pressure comes in. You hear the story, and everyone's story deserves help, and you want to help," Kanu, whose foundation has a waiting list of more than 1,000 children, says. "There was an incident last year when we were raising money for a family so that a child could have an operation. We'd organised a charity football match but on the morning of the game news came through that the child had died."

That match – Friends of Kanu v Pompey XI – took place at Fratton Park and Kanu has enjoyed a renaissance on the south coast which culminates in tomorrow's FA Cup final at Wembley against Cardiff City, having scored the winning goal against his former club West Bromwich Albion in the semi-finals. "I hope he remembers that," Kanu laughs. "He" is Harry Redknapp, the Portsmouth manager, and there is genuine warmth when the striker talks about his relationship with the man who brought him to the south coast when it appeared that his top-flight career in England was over at the start of last season.

It is curious to segue from life and death to football but it is something that Kanu has been doing for years. "Taking a club like Portsmouth to the final is a particularly great achievement," he says. "And it makes it more special because playing for Ajax or Arsenal you expect to win something or be in the final every year." Kanu has won the competition twice before – in 2002 and 2003 – but admits that "this time it's different".

He never regarded moving to Portsmouth as a demotion. "When I signed, David James and Sol Campbell signed as well, so I knew there were good players coming," Kanu says. "We did well last year and because of that more good players came. I encouraged John Utaka to join and now we have Jermain Defoe." Defoe is Cup-tied tomorrow, placing more responsibility on Kanu's shoulders. Not that he is remotely concerned. "I have scored in so many big games," he says. "It shows the kind of player I am."

And, with Redknapp, he believes he has the manager, also, that he needs. So what's Harry's secret? "He knows your capabilities," Kanu says. "He knows who you are and that's the most important thing. Some managers know what you can do but they keep it to themselves. Harry is not like that. He tells you who you are. He makes you feel appreciated. He makes you know you have talent and you have to express it, he makes you feel happy. It makes everyone more relaxed. Because of Harry, players want to go to Portsmouth and enjoy their lives and, with him, it can be a new life."

Which is something he, more than most, can appreciate.

For more information on Kanu's foundation, log on to: www.kanufootballfoundation.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments